Cleveland Institute of Art: quiet champion of biomedical arts

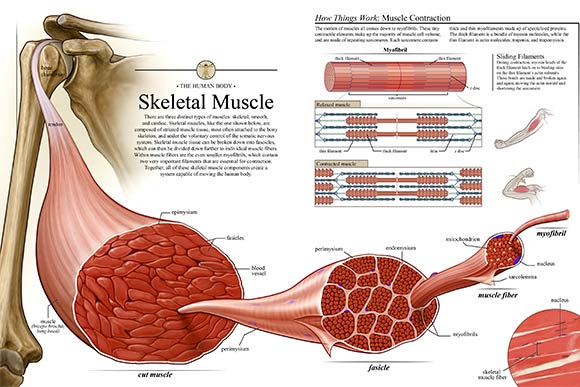

Whether you're biding your time in a doctor’s examining room, studying a textbook, watching an instructional video or searching your ailments online, biomedical art surrounds us. It educates, explains, examines, elucidates, diagrams, and dissects biological materials rarely seen with the human eye when words are not enough. Built on a strong foundation of science, cutting edge tools in biomedical art allow the artists to work in three dimensions, creating anatomical models, simulators, and prosthetics.

While known for flashy auto designs, runway shows and curated exhibitions, the Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA) is also perched at the forefront of this subtle yet complex field, training and guiding the artists who will take the business of combining art, medicine and science into the future.

An Incredible Way to Package Information

An Incredible Way to Package Information

Artist Rebecca Konte has always been fascinated with science.

"Art comes naturally to me, but science is what inspires me," she says. "When it became time to decide what I wanted to pursue in my undergraduate career, I felt torn between choosing art or science. It was not until I discovered the Cleveland Institute of Art’s Biomedical Art program that I realized I can truly do both."

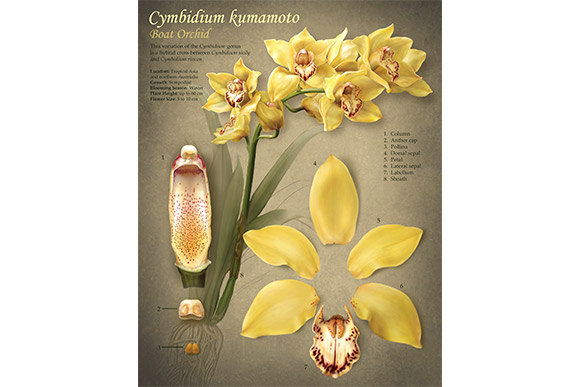

Now a senior in the program, Konte has collaborated with local institutions like the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland Botanical Garden, and University Hospitals.

She is currently spending the summer at San Francisco’s California Academy of Sciences illustrating a field guide of medically important mosquitoes. The task is in partnership with iNaturalist, a citizen science project and online social network of naturalists, citizen scientists, and biologists interested in mapping and sharing observations of biodiversity across the globe.

Rebecca Konte's Sheep Heart Dissection, one of the winners of the Award of Excellence Association of Medical Illustrators annual salon this past July

Rebecca Konte's Sheep Heart Dissection, one of the winners of the Award of Excellence Association of Medical Illustrators annual salon this past July

“Specifically, I am illustrating the species affecting Hawaii, some of which are vectors of serious viruses such as Dengue or Zika,” she explains. “The field guide’s goal is to provide a resource that the general public can use to understand mosquito anatomy and distinguish the major species from one another. With that knowledge, people can then locate, identify, and possibly reduce the number of mosquitoes in their area, thereby reducing the threat of infectious disease.

“Over the next year I will continue to illustrate for the field guide initiative, building the gallery of important mosquitoes. I hope that this field guide can positively impact people’s lives.”

Konte hopes to continue to create meaningful art that serves science, believing that the two intersecting fields have the potential to be mutually beneficial.

“Science is limitless for human knowledge and inquiry, and art is this incredible way of packaging that information so it can be seen, felt, and understood,” she says.

Konte credits CIA with introducing her to exceptional professors that improved her professional illustration skills and for opening doors in the industry. She adds that the most challenging aspect of her CIA experience has been balancing time between studies and social life.

“Art has a way of becoming all-encompassing,” she said. “Sometimes it becomes hard to take a break.”

A Unique Undergraduate Opportunity

Started in the late 1960s in conjunction with Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), the Biomedical Art program (called Medical Illustration prior to the mid-2000s), combines art, science and medicine. Students take their required studio classes at CIA, but take one science class per semester at CWRU, including a graduate level gross human anatomy course with full cadaver dissection.

The program permits a flexible course of study in which students can take courses in computer imaging and animation, editorial illustration, instructional design and multimedia, medical sculpture, surgical and natural science, business and professional practices.

Classes explore different techniques and mediums and range from carbon dusting, digital rendering, and interactive design, to 3-D modeling. Each Biomedical Art student has individual studio space and access to the latest digital technologies and high-end computer resources in addition to motion capture technology, 3-D modeling tools, a medical sculpture laboratory, and a suite of other laboratories with the latest software and tools for medical illustration. All instructors are board certified and practicing medical illustrators.

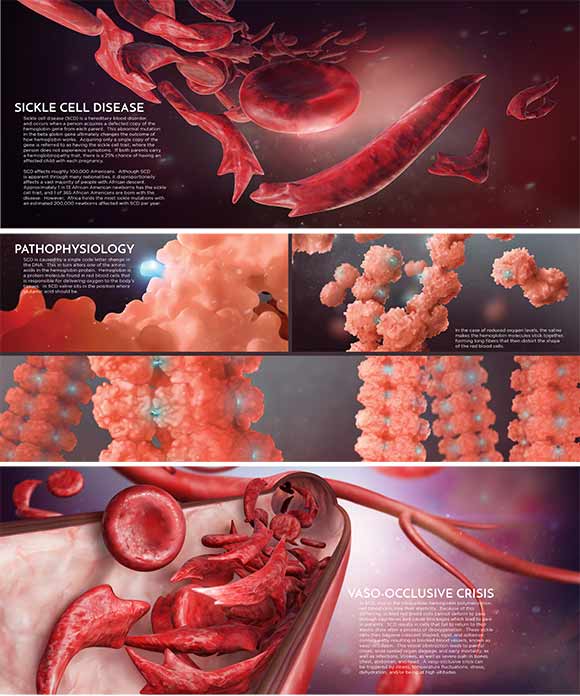

CIA student Grace Gongaware's Sickle cell piece, one of the winners of the Award of Excellence Association of Medical Illustrators annual salon this past July

CIA student Grace Gongaware's Sickle cell piece, one of the winners of the Award of Excellence Association of Medical Illustrators annual salon this past July

There are only three undergraduate programs similar to CIA's in that the curriculum mirrors that of the graduate programs. CIA's program is unique in that the students spend three years in the major and also create a senior thesis project similar in scope to those of graduate students. There are approximately 30 students in the program (sophomore through senior year), with 10 graduating on average annually.

Although most people think a degree from the program would naturally lead to a career in publishing - possibly as a textbook illustrator, associate professor and the chair of Biomedical Art program Thomas Nowacki says there is a wide-range of directions graduates can branch out into.

"Nowadays biomedical artists find themselves in all manner of creative positions," he says. "Medical animation (both 2-D and 3-D) is huge and usually entails being part of a larger studio - specifically in biomedical art or as the resident medical animator; creating interactive modules for patient education; [or in] litigation - illustrating or animating personal injury cases or malpractice for display as a courtroom exhibit. Later on in their careers, because they have experience in such a breadth of skills, they are well suited to being art directors in a studio environment - working in a science institution like the Museum of Natural History where they may help create exhibits. Many of these positions will be either as a solo contract illustrator/animators or part of a studio specializing in biomedical art/medical illustration."

In addition to his position at CIA, Nowacki also runs his own medical illustration and animation studio, Novie Studio. There he creates 2-D illustrations, animations and interactives.

"Often when a biomedical artist works in the field for a while, they prefer to begin their own studios," he explains, "which may stay small or grow into larger companies."

Five of the medical illustrators in Cleveland Clinic's Center for Medical Art and Photography graduated from CIA's program, and another recent graduate recently worked in Los Angeles for an animated Nickelodeon movie. In fact, one-third of the most recent graduating class has already found work in directly related professions.

"You can find CIA Biomedical Art alums at many of the local medical or scientific oriented institutions: The Cleveland Clinic, where two students intern each fall semester; University Hospitals, where our students view surgeries for their Surgical Illustration class; Cleveland Museum of Natural History and Cleveland Botanical Garden," Nowacki adds. "Outside of the state, a current newly minted senior is working at an internship in Boston at Visible Body, alongside a past alum of the CIA program."

Most commonly, medical illustrators and biomedical artists attend a graduate program in medical illustration, of which there are currently five in North America.

A Visual Component to Solutions for Parkinson's, Other Disorders

The Cleveland Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) Center has been employing students from CIA’s Biomedical Art program for a decade now. Established in 1991, the FES Center is a research consortium of the Department of Veteran Affairs, MetroHealth Medical Center, CWRU, and University Hospitals, although the organization does work with other institutions as well.

Providing a critical mass dedicated to developing neuro-technological solutions that improve the quality of life of individuals with neurological or musculoskeletal impairments, the Center focuses on implanted medical devices and the application of electrical currents to either generate or suppress activity in the nervous system. It's a fast growing field being applied to various conditions, such as sleep apnea. It's also concerned with deep brain stimulation for the control of Parkinson's Disease, eating disorders, and psychological disorders, among others. Currently, they have 65 research investigators each with their own research interests and projects.

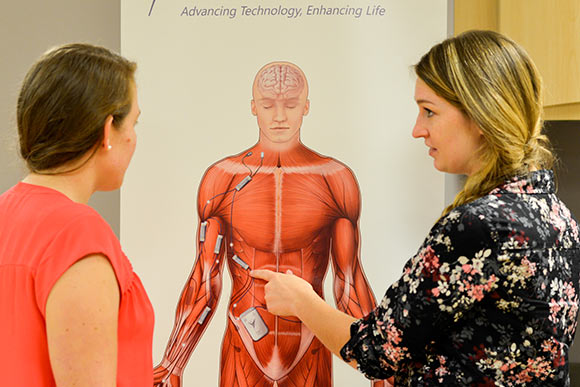

Erika Woodrum, FES Center Staff (CIA Biomedical Art 2014), works with Jeanette Coker (CIA student) editing video highlighting an FES Center research program

Erika Woodrum, FES Center Staff (CIA Biomedical Art 2014), works with Jeanette Coker (CIA student) editing video highlighting an FES Center research program

Biomedical Art students from CIA are often hired as interns at the Center for medical illustration, communicating complex medical information visually so patients, the public, and other medical professionals can better understand it.

The Center's communications manager Mary Buckett says that as the field continues to expand, so does their need for biomedical artists.

“We used to contract one at a time, but as the research center grew and our understanding of our need for this kind of support grew, we hired two with complementary skills that really provided us a better product,” she says.

Since then the organization has hired a graduate from the program full time and continues to contract one student intern from the program as well. They prefer to contract a student going into junior year and work with him or her for two consecutive years, due to the industry’s steep learning curve.

"It really benefits both sides," says Buckett.

Students prepare educational materials, drawings for presentations, illustrations for grant submissions, and material to help explain various research aspects to volunteers.

Lately, the FES Center has been utilizing the skills of more biomedical video and photography art students as more video clips are being used for grant submissions, progress reports, and information sent back to funding agencies.

"Communication in the scientific field is changing,” Buckett says. “It's moving from the written word to a more visual concept that is more easily grasped. [The students] are such a huge asset to our team… Video clips bring [researchers’] grant submissions to the top level when the funders are looking for concise information. If we can show the research participant doing the task, [funders] understand it that much better."

The Cleveland Institute of Art is part of Fresh Water's underwriting support network.