In their footsteps: Cleveland Restoration Society plans civil rights trail with historical markers

Memorable places in Cleveland's civil rights history

While the 10 sites have not yet been selected by Natoya Walker Minor, chief of public affairs for the city of Cleveland and head of the civil rights trail task force, top sites associated with Cleveland’s African American Civil Rights Trail being considered for the trail include:

Cory United Methodist Church: Cory is one of the oldest African-American churches in Cleveland and played a leading role in the civil rights movement, including numerous speeches by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X’s first iteration of his “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech.

The Ludlow Community Association, 1957: Significant as a neighborhood development model to counteract prevailing prejudice against black buyers in white neighborhoods. Subject of 2011 thesis by Shelly Stokes-Hammond (daughter of the late Congressman Louis Stokes), “Recognizing Ludlow—A National Treasure; A Community that Stood Firm for Equality."

Home of Ms. Dollree Mapp: Site of a significant event that sparked a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case regarding the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution as it relates to criminal procedure. Mapp spent seven years in prison until the court dismissed her case in 1961.

United Freedom Movement, founded in Cleveland, 1963: The United Freedom Movement, spawned by the NAACP, was a coalition of more than 60 groups that organized large public protests and demonstrations against inequality in housing, education and employment. During a 1964 coalition demonstration against the tactic of building segregated new schools to avoid integrating existing ones, protester Rev. Bruce Klunder was killed by a bulldozer on the site of Howe Elementary School, now demolished.

First “Straw Buy” House, 3558 Townley Road, Shaker Heights: House purchased in 1964 by white couple (Carol and Burt Milter) for a black couple (Ernest and Jackie Tinsley) to overcome racist real estate practices. Carol Milter worked for Operation Equality, a Cleveland housing program that provided loans to minority families and encouraged white families to stay put. Their work helped create an integrated community and spawned the formation of other such groups.

Hough riots (1966) at East 79th Street and Hough Avenue: Site of Cleveland’s most significant urban uprising against poor housing, criminal injustice and lack of public accommodation. Five days of rioting and violence resulting in the deaths of four people, 50 injuries, and 275 arrested. The event that forever changed Cleveland, it led to the election of Mayor Carl Stokes.

Glenville United Presbyterian Church: Significant for its association with Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference offices and events. Pastor Rev. David Zuverik co-chaired the United Freedom Movement Schools Committee.

Glenville Shootout and Riots (1968): Site of a gunfight between Black Nationalists of New Libya and Cleveland police, leaving six dead, leading to riots for four days. Each side claimed victims were martyrs in their cause.

Home of Mayor Carl Stokes: Carl Stokes was the first African-American mayor of a major American city, from 1967 to 1971. He built a biracial coalition to bring civil rights to Cleveland’s African-American citizens.

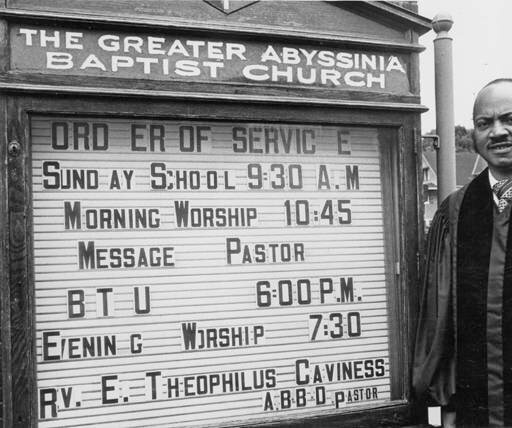

Greater Abyssinia Baptist Church: The Greater Abyssinia Baptist Church was affiliated with numerous groups, including NAACP, Congress of Racial Equity, and National Action Network (founded by Rev. Al Sharpton). The church served as headquarters for the United Freedom Movement, and Pastor Theophilus Caviness requested the presence of Dr. King after the Hough riots to prevent further disturbances and to assist in the campaign to elect Carl Stokes as mayor.

Cleveland is a significant city in the history of America’s civil rights movement. The city was home for the creation of the United Freedom Movement to oppose racism in schools, employment, and housing. Mayor Carl Stokes was elected in 1967 in Cleveland—becoming the first black mayor of a major U.S. city. The Hough riots in 1966 and the Glenville shootout and riots in 1968 marked the height of racial tension in the city. And the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made numerous trips to Cleveland in support of civil rights.

The United Freedom Movement, spawned by the NAACP, was a coalition of more than 60 groups that organized large public protests and demonstrations against inequality.While the struggle continues to this day as many Americans face inequities in housing, education, and the criminal justice system, the Cleveland Restoration Society plans to mark some of the most memorable moments and locations in Cleveland’s civil rights fight with a civil rights trail.

The United Freedom Movement, spawned by the NAACP, was a coalition of more than 60 groups that organized large public protests and demonstrations against inequality.While the struggle continues to this day as many Americans face inequities in housing, education, and the criminal justice system, the Cleveland Restoration Society plans to mark some of the most memorable moments and locations in Cleveland’s civil rights fight with a civil rights trail.

In October, the restoration society was awarded $50,000 from the National Park Service for its project “In Their Footsteps: Developing an African American Civil Rights Trail in Cleveland, OH.” The organization is one of 44 projects in 17 states collectively to receive more than $12.2 million in African American Civil Rights Grants to preserve and highlight stories related to the African-American struggle for racial equality in the 20th century.

The grant program is funded by the Historic Preservation Fund as administered by the National Park Service, Department of Interior.

“It’s thrilling,” says Margaret Lann, Cleveland Restoration Society’s manager of development and publications, of the news. They applied for the grant in September 2018 and got word that they had received the money this past September, she says. “It’s just affirming Cleveland’s role in that struggle. It’s sharing Cleveland’s story publicly.”

The project will install 10 Ohio Historical Markers—there are 707 bronze, Ohio-shaped markers across Ohio, which are 42 inches wide by 45 inches high, and stand seven feet tall—at the sites in Cleveland associated with the struggle for civil rights for African Americans between 1954 and 1976.

They wanted to use the Ohio markers because they stand out, Lann says. “They are extremely sturdy, and you can see them walking by or driving by,” she says. “You can stop and read them.”

By marking sites in Cleveland where events took place which were pivotal to changes in federal legislation and black empowerment, Lann says, Cleveland will honor the courage and steadfastness of those who brought about legislative and social progress. There is not a lot of historical recognition of Cleveland’s role in the civil rights movement, she says.

“When we looked at how many Ohio Historical Markers are across the state or in Cuyahoga County, there was a very small percentage that represented the fight for civil rights,” she says. “There was a lot of activity that went down in this area.”

The Greater Abyssinia Baptist ChurchNatoya Walker Minor, chief of public affairs for the city of Cleveland, will head the Cleveland Restoration Society’s Civil Rights Trail Task Force that is being created to choose the 10 sites.

The Greater Abyssinia Baptist ChurchNatoya Walker Minor, chief of public affairs for the city of Cleveland, will head the Cleveland Restoration Society’s Civil Rights Trail Task Force that is being created to choose the 10 sites.

The task force will be composed of residents involved with Cleveland’s civil rights movement, scholars, community leaders, and students.

The goal is to implement the 10 markers on the Civil Rights Trail over the next three years, Lann says. “We had to show [the National Park Service] there were at least 10, but we believe there are a lot more of them,” she says, noting that the Cleveland Restoration Society produced “Know Our Heritage: the African-American Experience in Cleveland” in 2012.

Site selection will be guided by published research from the National Park Service on The Modern Civil Rights Movement (1954-1964) and The Second Revolution (1964-1976), and nomination criteria for the National Register of Historic Places’ Twentieth-Century African American Civil Rights Movement in Ohio published by the Ohio Historic Preservation Office.

For more information, contact Stephanie Phelps, Cleveland Restoration Society marketing and events specialist, (216) 426-3106.