Happy Birthday Cleveland: In 225 years, we’ve had our moments

225 years of Cleveland highlights and lowlights

Here are a few highlights of history in Cleveland, which turns 225 this Thursday, July 22:

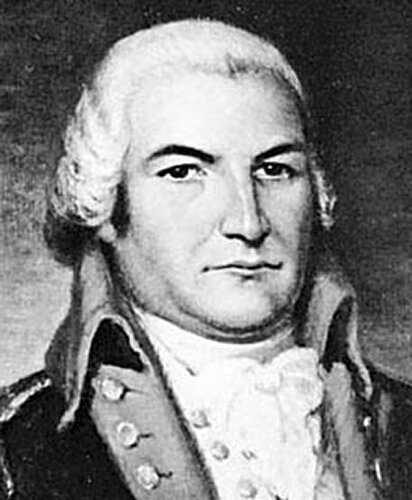

1796: Moses Cleaveland and his surveyors plot town and give it his name.

1809: First permanent Black settlers arrive—the family of George Peake, who invented hand mill for grain.

1814: Village of Cleaveland chartered.

1825-32: Ohio and Erie Canal built, linking the Cuyahoga River with the Gulf of Mexico.

1836: Cleveland, by now spelled as we know it today, becomes a city and fights a Bridge War with new City of Ohio (later Ohio City) over the Columbus Street Bridge.

1848: Abolitionist Frederick Douglass leads the Colored National Convention here.

1854: Cleveland and Ohio City merge.

1870: John D. Rockefeller and colleagues create Standard Oil, which will become world’s biggest business.

1892: Cleveland’s John P. Green becomes Ohio’s first African American state senator.

1901-1909: Noted Progressive Tom L. Johnson serves as mayor.

1908: The Collinwood School fire kills 172 children and two teachers, many of them died while jammed at exit.

1920 and 1948: Indians win the World Series.

1929: Cleveland Clinic fire kills 123 people.

1935: “Untouchable” Eliot Ness becomes Cleveland safety director, and the Torso Murders begin, baffling him.

1944: East Ohio Gas explosion kills 130 people.

1945: Cleveland Buckeyes win Negro World Series.

1945: Cleveland Rams win National Football League championship in final season here.

1946-1950, 1954-55, and 1964: Cleveland Browns win championships in All-American Football Conference and National Football League.

1966: Hough riots.

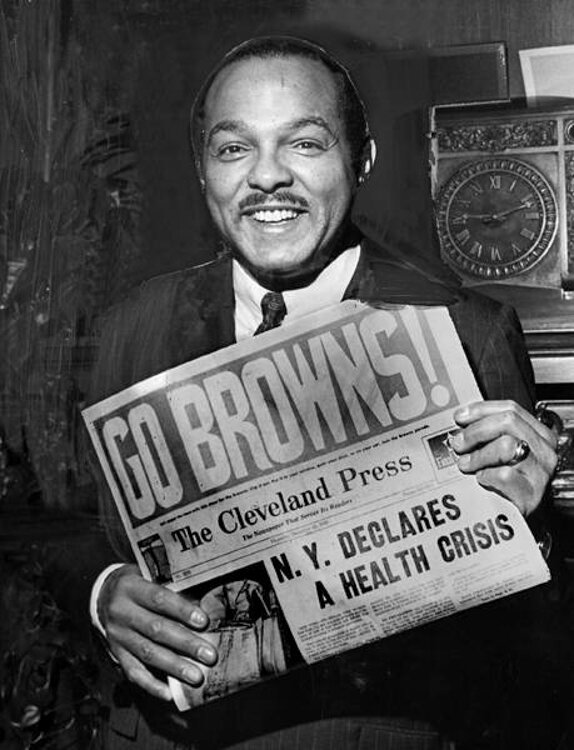

1967: Carl Stokes becomes first Black mayor of major U.S. city.

1968: Lawyer Louis Stokes is elected Ohio’s first Black congressman in the district formed because of his 1968 U.S. Supreme Court victory in Terry v. Ohio.

1968: The Glenville riots.

1969: Mayor Stokes publicizes latest of many Cuyahoga River fires, boosting environmentalism but hurting Cleveland’s reputation.

1976: Cleveland schools found guilty of segregation de jure, aggravating neighborhood differences.

1978: Bankers declare Cleveland in default.

1995: The Cleveland Browns announce move to Baltimore.

1999: The new Cleveland Browns take the field.

2008: FBI raids catch many officials in corruption probe.

2013: Michelle Knight, Amanda Berry, and Gina DeJesus win freedom after nine to 11 years’ kidnapping on Seymour Avenue by Ariel Castro.

2014: Police kill 12-year-old Tamir Rice, who had toy gun.

2016: The Cleveland Cavaliers win the National Basketball Association championship.

2021: Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson declines to seek re-election after Cleveland’s longest tenure as mayor—16 years.

Dates gathered from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History Timeline.

When marking milestones, we naturally tend to look back. That is, if we’ve noticed them.

Cleveland’s 225th birthday is drawing near with little fanfare so far. Word of tomorrow’s July 22 occasion surprises some locals and amuses others.

“225?” asks former Cuyahoga County Commissioner Mary Boyle. “Is that all?”

In many ways, the town has changed almost unrecognizably since 1796. According to Sustainable Cleveland, just 19% of the Forest City has tree cover today.

According to Roy Larick, local historian, geologist, and pioneer descendant, Greater Cleveland is down to about 60 Moses Cleaveland trees, which predate the city’s founding.

Meanwhile, the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie have been drastically remade by nature, development, and climate change. Beaches have washed away. Bluffs have crumbled. The river turned foul, caught fire, spurred the Clean Water Act, then grew somewhat cleaner itself.

Through most of the 20th Century, we used our waterways mainly for transportation and power. Now we use it mainly for exercise and fun.

Still, Larick sees at least one constant over those 225 years. Native American leaders took bribes from the settlers. Recent leaders have kept up that tradition.

A few celebrations

A few celebrations

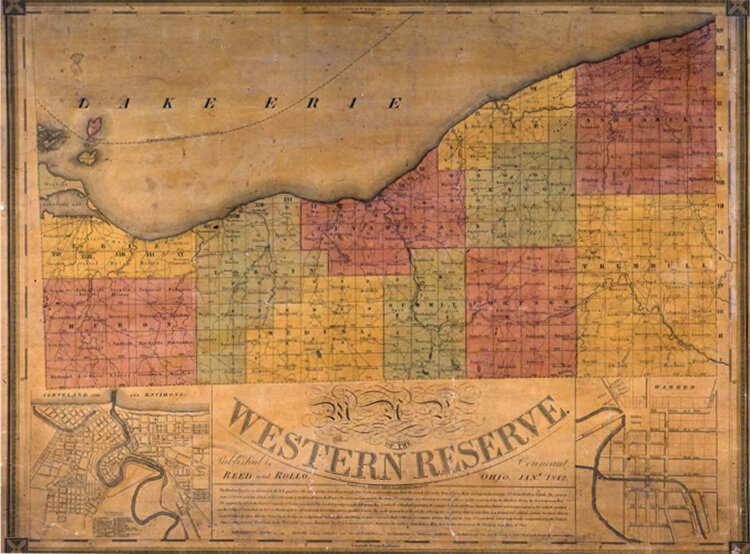

Moses Cleaveland and his band of surveyors were hardly the first people here or even the first whites. But they plotted the town, named it, and declared it the capital of the Connecticut Western Reserve, so they’re considered its founders.

We held big celebrations of their arrival’s centennial, sesquicentennial, and bicentennial. For the 225th, though, only modest events have been held or announced.

On July 3, the Early Settlers Association of the Western Reserve gathered in Conneaut, the surveyors’ first stop in the Reserve. At 11 a.m. on Thursday, July 22, members will hold their yearly observance of Cleveland’s birthday at Public Square. On Friday, July 23, the group will gather at noon in the southeastern corner of the Reserve, in what is now Poland Township in Trumbull County, where some surveyors drove a post.

For more details on these events, click here.

Identity and abandonment questions

Throughout the years, Cleveland has had something of an identity problem. It’s known as part of the Western Reserve, Northeast Ohio, the Midwest, the North Coast, and the South Shore.

Early on, the city prospered from straddling the continent’s northern and southern watersheds, shipping via canals and natural waterways in all directions. Now it struggles with competition from the coasts and the Sun Belt.

Cleveland has inspired many slogans and sayings that praise or pan the town: Best Location in the Nation. Cleveland’s a Plum. The Best Things in Life are Here. Mistake on the Lake. You Gotta Be Tough. Believe in Cleveland. Defend the Land. Cleveland Against the World.

From the start, Cleveland has seen many disappearing acts. Moses Cleaveland left soon after he arrived. The first “a” in the town’s name vanished before long.

John D. Rockefeller took his mighty Standard Oil to New York. British Petroleum shut down Sohio.

Native son Lebron left twice. The original Browns departed, and so did the 1936-1945 Cleveland Rams—still the only team to do so right after a National Football League crown.

Many products have skipped town, too, from Lifesavers to Dirt Devils.

Our mob sent much of its loot to Las Vegas before pretty much blowing itself up.

We razed most of our famous Millionaire’s Row and other historic buildings. Yet we saved Playhouse Square from demolition and gave it the biggest capacity of any U.S. theater complex outside of New York’s Lincoln Center.

We razed most of our famous Millionaire’s Row and other historic buildings. Yet we saved Playhouse Square from demolition and gave it the biggest capacity of any U.S. theater complex outside of New York’s Lincoln Center.

Preservation and equality

Preservation is just one of several fields in which Cleveland has triumphed and flopped. “It’s a tale of two cities,” says Rev. E. Theophilus Caviness, 93, a former city councilperson.

Take the economy. We’ve gone from subsistence to wealth, to default, to a tentative comeback.

Or take inclusion. Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes was just one of our many Black trailblazers.

In sports alone, we’ve had the Indians’ Larry Doby and Frank Robinson; the Browns’ Marion Motley and Bill Willis; and the Cavs’ Wayne Embry.

Basketball’s John McLendon pioneered several tactics and set two firsts as head coach of the Cleveland Pipers and Cleveland State. Track and field’s Jesse Owens became the first American to win four gold medals in the same Olympics—Munich’s 1936 games, meant to showcase the Aryan race.

The insurrectionist John Brown became the best-known of many Northeast Ohio abolitionists. Oberlin College and Conservatory was the first U.S. college to graduate a Black woman.

Akron hosted an early woman’s rights convention, where former slave Sojourner Truth reportedly asked, “Ain’t I a Woman?”

Cleveland Cultural Gardens - Ukrainian GardenIn the 20th century, Cleveland opened the unique Cultural Gardens.

Cleveland Cultural Gardens - Ukrainian GardenIn the 20th century, Cleveland opened the unique Cultural Gardens.

Yet Cleveland is one of the nation’s more segregated and unequal cities. Its schools were found guilty of segregation de jure—that is, segregation even more extreme than housing patterns. We’ve seen Black violence, white violence, and blue violence.

Our many waterways and bridges have united and divided us. In 1836, East and West Siders fought the “Bridge War.” In 1966, during the Hough riots, someone destroyed the Sidaway Bridge, which had linked the mostly Black Kinsman neighborhood to the mostly white area known today as Slavic Village.

The bridge ruin still dangles over a ravine. So, it’s only fitting that a group called the Society for Creative Anachronism dubbed Cleveland the Cleftlands.

Strength and weakness

Local healthcare is similarly double-edged. Our acclaimed hospitals have made breakthroughs with transfusions, bypasses, angiograms, defibrillations, dialysis, transplants, artificial hearts, serotonin, and much more.

Yet we have one of the nation’s highest rates of infant deaths. And life expectancy varies about 20 years between a Fairfax census tract and a Shaker Heights—fewer than five miles apart.

We’ve also lost many lives to disasters—natural or man-made.

Garrett Morgan rescues a victim of the Waterworks Tunnel Disaster, July 1916.But Garrett Morgan rescued some victims of a Cleveland Waterworks explosion while wearing his patented gas mask. Morgan also created a traffic signal device, a hair straightener, an African American country club, and part of today’s Call & Post.

Garrett Morgan rescues a victim of the Waterworks Tunnel Disaster, July 1916.But Garrett Morgan rescued some victims of a Cleveland Waterworks explosion while wearing his patented gas mask. Morgan also created a traffic signal device, a hair straightener, an African American country club, and part of today’s Call & Post.

Morgan exemplifies one of Cleveland’s fairly consistent strengths. We innovate. In whole or part, we pioneered traffic signals, electric streetlights, fish hatcheries, rubber-core golf balls, Tommy Guns, alkaline batteries, alligator clips, salt tablet dispensers, infomercials, health museums, housing authorities, and free public computer networks, and many other things. We were the first to deliver mail for free and to film heists of banks.

Case Western Reserve University has produced 16 Nobel laureates. NASA Glenn Research Center holds more than 725 patents for technology used from Earth to Mars. Sherwin-Williams introduced the first commercially successful ready-mix paint, resealable can, and latex interior wall paint.

Among many other strengths are our beloved parks and restaurants. And we still have proud unions, though they’re shrinking here as they are elsewhere.

We’re strong in philanthropy, having started the first community foundation and first community chest. In that field and most others, we’ve been boosted by our many newcomers.

“Go from the [University Hospitals] Hanna and Mather pavilions to Seidman and Ahuja,” says John Grabowski, senior vice president of the Western Reserve Historical Society. “If you want to be part of the club, you have to do what the club has done from the beginning: Give back.”

We’re strong in arts and culture. We have the renowned Cleveland Orchestra, the historic Karamu House, the Rock Hall, the National Cleveland-Style Polka Hall of Fame, leading libraries, and museums specializing in everything from “A Christmas Story” to witchcraft.

We’ve produced many popular comic strips, graphic novels, and comedy acts. Cleveland: You Gotta Be Funny.

Speaking of humor, how about our teams? The Indians have lost their last two World Series in extra innings of the final game. They also own the majors’ longest current streak without a crown. But the Browns have reawakened, and the Cavs are the only team to win the National Basketball Association finals after trailing three games to one.

A Christmas Story House in TremontUnconditional love

A Christmas Story House in TremontUnconditional love

For all our problems, locals still praise the town. They say it’s affordable, convenient, and friendly. There seem to be almost no degrees of separation here, just a few memory lapses.

Former Congresswoman Mary Rose Oakar says flatly, “Cleveland is a fantastic city. There isn’t anybody who comes to Cleveland that doesn’t fall in love with the city.”

Grabowski says that Cleveland will have an advantage awhile because of climate change. The West is drying up, but not the Great Lakes—the world’s second biggest source of fresh water.

Former councilperson Caviness says, “The struggle continues. Patience is a virtue. Overall, I am really happy with how we’ve handled many major problems that have inflicted other cities. I think Cleveland’s going to be all right.”

Bill Barrow, head of the Early Settlers and of Cleveland State University’s special collections, says he thinks the nation’s formerly fifth-biggest city could become prosperous again without being populous.

“I’m upbeat,” he says. “With the Clinic and the Orchestra and the river and the lake, we’ve got a lot going.”

Robert Madison, 97, the Ohio’s first Black architect, says, “We’ve got everything here, including the infrastructure for greatness. The people will gradually come back.”

Commissioner Boyle says, “Years ago, we thought Cleveland had amazing possibilities.”

And now? She chuckles. “Cleveland still has amazing possibilities.”

Think you know Cleveland? Be sure to take our quiz today. The answers will be published tomorrow.

To learn more about Cleveland’s rich history, see case.edu/ech, teachingcleveland.org, or clevelandhistorical.org.