Cleveland muscle: art on wheels

From screamin' sports cars to towering monster trucks, Cleveland is host to unique design stories born on the wings of transportation. This effort from Fresh Water contributor Hollie Gibbs rolls down the creative highway between Cleveland and Detroit, meets a man whose artistic vision is pure Rust Belt gold and another who elevates bicycles to fine art.

Imported from Cleveland

Look out on the road with local pride. When you see a 2014 Corvette, 2014 Viper, 2016 Challenger Hellcat, or 2016 Pacifica, you are witnessing designs in action that were inspired by Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA) alums Jose Gonzalez, Scott Krugger, Nicholas Vardis, and Irina Zavatski, respectively.

"These are some bad-ass looking cars," says Mark Inglis, CIA's vice president of marketing and communications, noting that the tether between CIA and those smokin' wagons should surprise no one.

"We're one of the top three undergraduate programs for transportation design," says Inglis, adding the school's Industrial Design program, of which the associated Transportation Track is a part, was founded by Viktor Schreckengost in 1931.

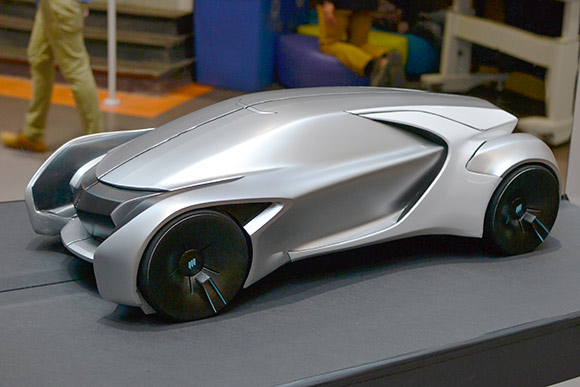

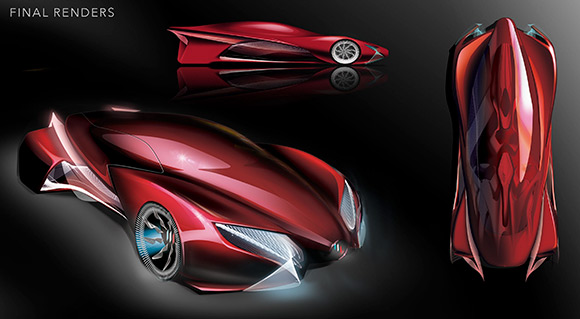

Buick design by CIA student David Porter

Buick design by CIA student David Porter

"We go back many, many generations," says Inglis, "and we have a lot young designers up and down the food chain with the Big Three auto makers - and some really big heavyweights."

There is indeed CIA talent behind some of our hottest wheels as well as our everyday rides including alums Kirk Bennion, design director behind many generations of the Corvette; Joseph Dehner, who heads Dodge and Ram design at Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA); Holt Ware, director of Buick exterior design at General Motors (GM); Jerry Hirshberg, who created Nissan’s Design Studio in San Diego in 1980; and Phillip Zak, executive director of design at GM's Pan Asia Technical Automotive Center in Shanghai.

"We're really known in the industry," says Inglis.

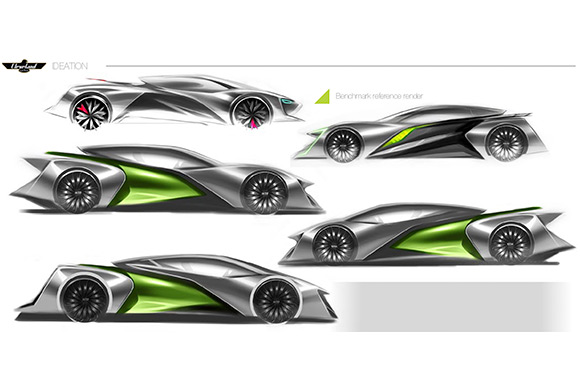

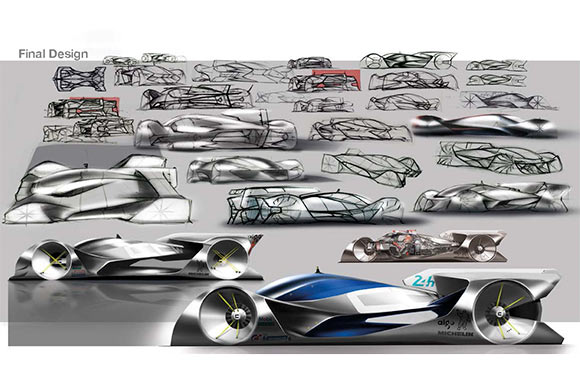

The Industrial Design program annually graduates approximately 20 students poised to take their place in the multi-dimensional field. The collaborative, solution-driven program helps students develop skills in visual communication, form development, and presentation as they study drawing, modeling, and computer-aided design.

In particular, students in the department’s Transportation Track often get on the road to Detroit and those Big Three.

“CIA has a good connection with GM, FCA and Ford,” CIA’s associate professor of Industrial/Transportation Design Haishan Deng explains. “CIA's connection with the auto industry dates back to 1939. Notably, CIA grad Joe Oros (Class of 1939) was credited with leading the design team for the iconic 1964 Ford Mustang. Today, there are many CIA alumni working as design directors, managers, and designers at these companies.

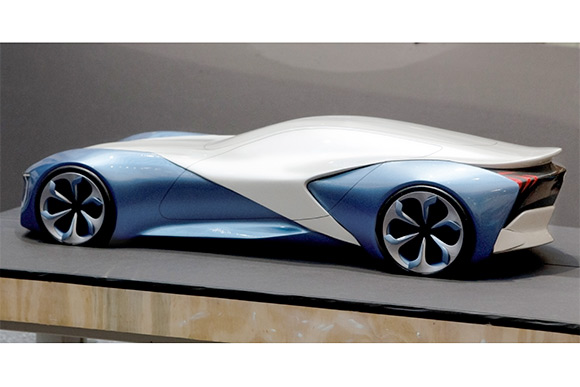

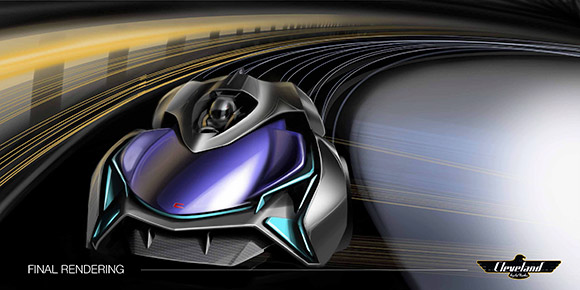

Design for Cleveland Cyclewerks by CIA student Jichen Fang

Design for Cleveland Cyclewerks by CIA student Jichen Fang

“The auto industry in Detroit has become very supportive for CIA's transportation program financially and academically,” Deng continues. “Every year, GM and FCA will sponsor a student design project with CIA. Directors and designers from Detroit come down and review student works during the semester. Students also have a chance to visit the design center of the auto manufacturer to get to know the real design environment. During the summer, students intern at these companies, and in many cases, the experience evolves into full-time employment.”

Last semester, students worked with GM for a Buick design project exploring concept vehicles reflective of lifestyles, technologies, and Buick brand literacy for the year 2030. The professionals included design managers, exterior and interior designers.

“Students will learn from them a lot of different skills that are needed for automotive design,” Deng says. “As for the sponsor, it is a great opportunity to discover talented students.”

The department does not limit itself to vehicles of the four-wheeled variety. Currently, students are working on a project with local motorcycle manufacturer Cleveland Cyclewerks.

“The project is to explore product line possibilities for Cleveland Cyclewerks in 20 years,” Deng explains. “There are a variety of solutions that are not limited to motorcycles.

Imagining a Fierce Metal Empire

Should you spot a large, metallic, two-headed dragon cruising down the highway this summer, don’t fret. It’s just local automotive artist Tim Willis taking one of his larger-than-life automotive creations on the road now that the weather is fair.

Willis has created 19 oversized specialty vehicles in all. While some occupy a warehouse on West 65th Street, many adorn his East 83rd Street yard. A monumental transformer keeps guard just past the gate with a colossal k-9 on a leash among monster trucks and other spectacular machines.

Tim Willis's fierce metal empire

Tim Willis's fierce metal empire

His fierce metal empire grew from humble beginnings. Willis dropped out of East Tech High School after ninth grade following the deaths of his father and three siblings to the same rare, genetic heart disease within a three-year span. Willis felt that time was not promised to him, and he didn’t want to spend whatever time he had left in school.

“I told my mom, if I’m going to die, I’m going to enjoy my life,” he says. It didn't go over well. His mother kicked him out of the house.

Willis moved into an abandoned home nearby and began working for tools at a local auto junkyard to learn about cars. His love of autos grew as he spent 23 years entertaining crowds at monster jams, performing wheel stands and burnouts in his trucks. He put away enough money to spend the rest of his time living frugally and creating his art.

“Everything you do in life involves math and science,” Willis says, “put that together with imagination, that’s how I got started. Practice makes perfect. I want a challenge. I don’t want nothing easy. I don’t like simple. I don’t want something that anybody can do. That’s not impressive … The more I do, the better I get. Even as I’m working on one project, I’m thinking how I can make the next one better.”

He always displays his creations at shows, festivals, fairs, and events for free so the venue cannot charge people to admire or photograph them.

“I don’t want to make money for something I love doing,” he says. “I don’t look forward in the future. I’m living for right now.”

His larger-than-life portfolio has grown so large that keeping it on his property raised some zoning issues, so Willis had the residential house he was raised in torn down leaving only the commercially-zoned garage, thus making the property approved for commercial use. Currently, that enormous transformer at the front of that property is housing a bird’s nest.

“I won’t move that robot,” he declares. "I won’t disturb the eggs. Never mess with nature.”

As for the two-headed dragon he's reanimating in back, Willis already has $49,000 invested in it, a figure that will grow to about $125,000 when it’s finished. When complete, the beast will shoot red smoke; have moving heads, each with no less than 168 sharp teeth; and its wings will be fitted with 12- by three-foot solar panels. In all, it will take him about six months to complete.

“Imagination is the key to creativity,” he says. “If the kids approve, I know it’s good.”

Two Wheels, Completely Custom

Every good driver knows to watch for bikes on the street, but Dan Polito, of Cicli Polito, creates bicycles that turn fleeting glances into longing stares. Each one of his singularly unique creations takes many factors into consideration. He builds the bikes according to the rider’s body measurements (arm length, leg length, height, weight, knee position, shoe size, etc.), riding position, and center of gravity.

Polito also strives to create the best performing machine for each specific situation in his Stockyards neighborhood shop.

Dan Polito in the workshop at Cicli Polito

Dan Polito in the workshop at Cicli Polito

“If someone wants a race bike, that bike has to fit their particular race position, has to handle the lines in the corners appropriately, etc.,” he explains. “If someone wants a commuter for year-round riding, that bike has to be comfortable, durable and provide the means for attaching fenders, lights, racks, etc.

"The bicycle is a machine, and as such it is my job as a frame-builder to build the best functioning bicycle I am able to for my customers.”

Polito began basic bicycle maintenance as a young avid cyclist. Then he started helping a close friend repair Italian and French racing bicycles from the 1960s and 1970s.

“While learning about these European frame-builders, and also of their American counterparts, it dawned on me that these were actual people who had made these bikes,” he recalls. “I realized that is exactly what I wanted to become.”

He went on to study with a master frame-builder in Michigan before opening his Cleveland shop. He hopes to eventually bring finish (paintwork) completely in-house using 100 percent water-based or waterborne finishes.

“Automotive/commercial paint and finishing has come a long way, and the transition to full water-based paint shops is finally becoming a possibility here in North America,” he explains. “I'd like to do this with a bicycle specific paint shop, and do it as low-impact as possible. That involves some very significant expenditure though, so it’s still early in the planning stages on that one.”

Currently, he’s been receiving a lot of inquiries for performance road bicycles that accept larger width tires, but he has also gotten some more unusual requests over the years.

“Possibly the strangest was being asked to build a bicycle that used four small rocket thrusters to hover on demand,” he says. “That one did not quite make it.”

Cleveland Institute of Art is part of Fresh Water's underwriting support network.