Nourishing bodies and minds: Local colleges fight student hunger during the coronavirus pandemic

Taking five classes at once is a heavy load for any college student, but for 26-year-old Marcus Thornton, it sometimes feels like a crushing weight. That’s because the computer science major at Cleveland State University (CSU) is also working full-time to pay for tuition and living expenses.

Even though he works three nights per week at the Amazon fulfillment center in North Randall, sometimes it’s still not enough to make ends meet.

At times, Thornton has struggled to pay for rent, utilities, and food. He lost his job at a fitness center during the COVID-19 pandemic, compounding his problems, and was living at home with his family. But after they were evicted, Thornton ended up homeless and sleeping on friends’ couches until he recently moved into an apartment in Shaker Heights with a friend.

Food distribution bags ready to go at Lift Up Vikes! at Cleveland State University.Twice in the past year, when he was hungry and didn’t have enough money to buy groceries, Thornton visited Lift Up Vikes! Resource Center and Food Pantry at CSU. He left with a bag of fresh produce, canned goods, grains like rice and oatmeal, bread, and fruit juice.

Food distribution bags ready to go at Lift Up Vikes! at Cleveland State University.Twice in the past year, when he was hungry and didn’t have enough money to buy groceries, Thornton visited Lift Up Vikes! Resource Center and Food Pantry at CSU. He left with a bag of fresh produce, canned goods, grains like rice and oatmeal, bread, and fruit juice.

“They were friendly and had pretty good stuff,” he says. “It was a positive experience.”

Thornton is not ashamed of seeking help. Although he’s endured many challenges, he’s determined to get through school.

“As a full-time, first-generation college student, I don’t have the support system that many students have, especially considering my age,” says Thornton. “I don’t really have help from my family. I use as many resources as I can because I’m doing this on my own.”

Holly Fish, coordinator of Lift Up Vikes! says the university has stepped up to provide emergency aid to students during the pandemic. Student need has increased during this time, especially since many students work in hospitality, restaurants, and other industries heavily impacted by COVID-19.

“We know [the food pantry] is going to be extra needed this year,” says Fish. “A lot of our students were laid off during COVID.”

Nationally, around half of all community college students and as many as one-third of students at four-year colleges were affected by food and/or housing insecurity even before COVID-19, according to the Hope Center for College, Community and Justice, an action research lab housed at Temple University.

In a recent survey of 135 institutions across 36 states, nine of 10 institutions responded they were looking for extra resources to help students during the pandemic.

Now, as colleges reopen—even as the COVID-19 pandemic continues—they’re adjusting and expanding the ways they are helping students. In addition to pivoting to contactless pickup for necessities like food and toiletries, many are also providing emergency aid.

Yet, even as institutions acknowledge that providing for basic needs is important for college success, they’re also struggling to reach students who are at risk of being disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.

Kent State University (KSU). “If the student doesn’t do well, then they won’t be able to finish college and complete their degree. If we don’t retain the student, what are we going to do? We need to serve the whole student to be successful.”

Kent State University (KSU). “If the student doesn’t do well, then they won’t be able to finish college and complete their degree. If we don’t retain the student, what are we going to do? We need to serve the whole student to be successful.”

Going virtual

Woodyard says that KSU’s Campus Kitchen program is used to donate food off campus to help their neighbors but now the majority of the food now goes to students, faculty, and staff. The need was always there, she says, but now it’s being recognized.

“We’re a working-class institution,” says Woodyard of KSU, with 29% of its students eligible for federal Pell grants that are targeted to low-income families. “The communities they come from have a higher rate of food insecurity, and those issues don’t disappear when the student sets foot on campus.”

Campus Kitchen has two pantry sites that regularly serve both people on campus and in the neighborhood. Woodyard says they’ve been slammed since March, when they regularly began seeing 60 to 70 people per shift, compared to 15 people per shift last year.

KSU gave out 30,272 pounds of food from March to August—more than the school distributed during the entire last academic year.

“When COVID-19 hit, we made the decision to stay open and meet student needs,” says Woodyard. “The messages that we were receiving were people saying, ‘This is my lifeline, this is my family’s lifeline during this time.’ You hear about people losing their jobs, but this was up-close.”

With the aid of a $1 million grant from the Char and Chuck Fowler Family Foundation, Lift Up Vikes! recently opened a food pantry and resource center in its student center, quadrupling its capacity. Although the pantry was closed during the spring shutdown, student aid has soared during the pandemic. From January to May, CSU saw a 500% increase in applications to the Fowler Emergency Fund—from 104 to 490—and distributed more than $83,000 in aid.

“There is definite growth in stress overall in students,” says Katharine Bussert, clinical case manager at CSU. “Students are having trouble managing the uncertainty that the pandemic has brought as well as the isolation. What we’ve done to adapt is make ourselves available immediately.”

To prevent the spread of COVID-19, the Lift Up Vikes! food pantry places limits on the number of people who can visit the facility at one time and allows students to register virtually. Students pick up bags of groceries instead of shopping for individual items.

Alison Doehring, director of the Zip Assist program at the University of Akron, says during COVID-19, the school’s Campus Cupboard program pivoted to drive-up food distribution. University of Akron has seen a 120% percent increase in applications to their Student Emergency Financial Aid (SEFA) program since the start of the pandemic.

Alison Doehring, director of the Zip Assist program at the University of Akron, says during COVID-19, the school’s Campus Cupboard program pivoted to drive-up food distribution. University of Akron has seen a 120% percent increase in applications to their Student Emergency Financial Aid (SEFA) program since the start of the pandemic.

One of the keys to success, says Doehring, is reducing the stigma around student aid. “That’s why we don’t call it a pantry,” she says. “There’s a stigma around food insecurity, and we recognize that. We try to use language that reduces barriers.”

Ensuring student success

Although meeting basic student needs was not always front and center on college campuses, many of these institutions now see this as a critical aspect in retaining students and helping them complete their degrees.

“There’s an increasing recognition that addressing student needs is part of a persistence and completion strategy,” says Carrie Welton, director of policy with the Hope Center. “We’ve seen an increase in the cohort of institutions that are taking this on.”

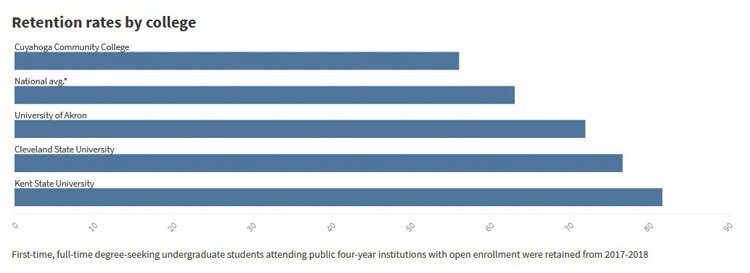

Nationally, college retention rates at many four-year public institutions are low. Just 63% of first-time, fulltime undergraduate students attending public four-year institutions with open enrollment were retained from 2017 to 2018, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Kent State retained 81.6% of its college freshmen in 2019 and graduated 65.6% of its 2014 cohort. University of Akron retained 71.9% of its 2017 freshman class and graduated 43.1% of its 2011 class.

CSU currently has a freshman retention rate of 76.6%, the highest in its history, normally averaging 72%. Tri-C has a 21% graduation rate, a transfer rate of 23%, and a retention rate of 56% percent, according to spokesperson John Horton.

“All these programs, that’s why they exist, because we want folks who are already invested to stay,” says Doehring. “It’s a tipping point. When I meet with a student who is behind on rent and still trying to find a job after being laid off, if that student gets evicted, they’ll go back home. These are first-generation low-income students. Will we ever get them back into higher education? What disservice are we doing by not working to keep them?”

Yet to be successful, colleges and universities must go beyond meeting basic needs, says Welton. “Our systems were failing students even before the pandemic,” she says. “It’s important as we move towards solutions at the institutional, state and federal level, we look beyond immediate needs. We don’t want to just put a band-aid on a bullet wound.”

Temple University’s Hope Center advocates helping students access SNAP, Medicaid, and other benefits. They also recommend that faculty include a basic needs statement on course syllabi, letting students know how they can access help if they need it. “We support the idea of telling colleges to get student-ready rather than telling students to get college-ready,” says Welton.

One of the challenges for schools is finding money to pay for meeting student needs, especially during COVID-19. “We used to do food drives, but we can’t do that during the COVID-19 pandemic, so now we have to get creative in how we get donations,” says Chavilah Witt, director of engagement and athletics at Cuyahoga Community College (Tri-C).

In addition to placing large bins of dry food, toiletries, and other supplies by the college entrance during the shutdown, Tri-C has also helped students in other ways. From March to May, the college awarded emergency funds to 560 students—four times the total fund in all of 2019. More than $4 million in CARES Act dollars have also been distributed to more than 3,000 Tri-C students, with the average award being nearly $1,400, according to the school.

Julia Krevins, director of the Institute on Poverty and Urban Education at Tri-C, said that to reduce barriers, schools should place resources at the center of campus, market them widely, and do personal outreach to at-risk students. Krevins says a recent student survey conducted by the institute found that 20% of Tri-C students are worried about going hungry; 20% are missing meals one time or more per month; 35% are worried about missing rent or mortgage payments; and 15% are worried about going homeless.

Unfortunately, too many schools do not recognize or proactively address the problem, says the Hope Center’s Welton.

“I wish more people recognized that this is a period of students’ lives when they really need support, so they don’t have to take classes from their cars or go to the library to use a computer,” says Krevins, stressing that college is a key to economic mobility. “Working through college just isn’t that realistic anymore.”

“Society tells us pulling yourself up on your own is the only way to be successful,” adds CSU’s Bussert. “I encourage students to notice when they are struggling and give themselves credit and compassion and not fall into comparison traps. It says nothing about your character in a negative way, if anything it demonstrates an individual's commitment to showing up for themselves.”

Welton says that ultimately, changes are needed at the federal and state level to support students. The Hope Center supports the Food for Thought Act, which was introduced in the US House of Representatives in July and would implement a pilot program to award grants to community colleges so that they could provide free meals to eligible students.

“Federal and state governments have been disinvesting in higher education for years, and the burdens of paying for it have been shifting to families,” says Welton. “This is only going to become worse after the pandemic.”

Want to help? Campus Kitchen at KSU, Campus Cupboard at U. of Akron, Lift Up Vikes! at CSU and Tri-C are all in need of monetary and food donations.

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 20-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets, including FreshWater Cleveland. Lee Chilcote is editor and founder of The Land and Asha Fairley is a junior at Cleveland State University and a fall intern with The Land.