Digital Divide: CMSD, nonprofits, and providers scramble to get students online for remote learning

With Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD) soon returning to school in a remote-only format, the district is currently in a mad dash to prepare students, teachers, and families for the start of school with the COVID-19 pandemic still looming large.

Schools are going virtual, and the district has its work cut out for it. By some estimates, Cleveland is deemed one of the worst-connected large cities in the country—and students start returning to class as early as next week.

The COVID-19 pandemic this past spring revealed a glaring divide: Two-thirds of students in the CMSD don’t have access to a computer and 40% of families don’t have internet access at home, according to a survey of parents conducted by CMSD after the schools in March closed and classes moved online.

As the pandemic continues, CMSD has purchased or ordered about 27,000 laptops and tablets and about 13,500 Wi-Fi hotspots (in a school district with an enrollment of about 40,000 students) as CMSD next week returns to remote learning for the first nine weeks of the school year (year-round students return to class on Thursday, Aug. 24, while traditional students will start on Tuesday, Sept. 8).

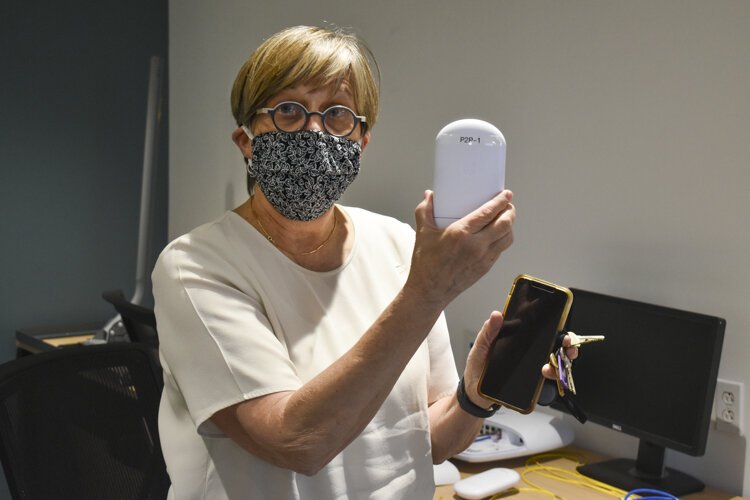

Dorothy Baunach, CEO of DigitalC, shows off a receiver device that the Cleveland-based nonprofit uses to provide high-speed Internet to residences in neighborhoods throughout the city that typically lack Internet access.The move comes at significant expense. The district has paid about $11 million for the devices and $3 million for the hotspots and one year’s worth of data—funded through a mix of CMSD funds, federal CARES Act money, and grants, according to a CMSD spokesperson.

Dorothy Baunach, CEO of DigitalC, shows off a receiver device that the Cleveland-based nonprofit uses to provide high-speed Internet to residences in neighborhoods throughout the city that typically lack Internet access.The move comes at significant expense. The district has paid about $11 million for the devices and $3 million for the hotspots and one year’s worth of data—funded through a mix of CMSD funds, federal CARES Act money, and grants, according to a CMSD spokesperson.

When the district’s remote-only classes begin this month, CMSD CEO Eric Gordon says the district will be in good shape.

“We’ve already distributed about 15,000 devices and about 9,400 hotspots over the summer, and we’ve ordered an estimated 10,000 devices and another 4,000 hotspots,” he says. “We believe in the fall when we finalize our distribution that we’ll be close to, if not at, a one-to-one environment for kids. That’s one device per student, either iPad, Chromebook or laptop.”

However, Gordon says teachers and student families need to be trained on using the technology, and once these families no longer have a CMSD student, they’ll need to give the equipment back.

But it’s an immediate solution that school districts across the country are racing to achieve as schools reopen for the fall.

Chicago Public Schools (CPS), for example, recently announced a $50 million program to bring free internet access to 100,000 CPS students over the next four years (funded by the likes of philanthropists and Michelle and Barack Obama).

Likewise, the Cleveland Foundation and Cuyahoga County recently announced a $4 million program, in partnership with T-Mobile, to provide 10,000 computers and 7,500 Wi-Fi hotspots to student families.

Catherine Tkachyk, chief innovation officer for Cuyahoga County, says the hotspots will be rolled out to families at school districts across the Greater Cleveland area, while the county is working with non-profit PCs for People to provide 10,000 devices before school starts.

Spanning the digital divide

Gordon says it’s important to keep in mind that Cleveland’s issues with internet access are not limited to the realm of K-12 education.

“When we shut down in Ohio, we told people, ‘go home, stay at home, apply for unemployment online, apply for jobs online, go to school online, go to your doctor online,’” explains Gordon. “This is not [just] a school problem, this is a problem of the internet not being a public utility in this country.”

Jovanti Ramirez, a student at CMSD who has a summer internship with PCs for People, works to sort mice and other devices out of a bin in their warehouse.If the Internet were treated like a utility like water or electricity—funded by taxes and protected by further regulations—there wouldn’t be such a problem with a lack of access, advocates like Gordon argue.

Jovanti Ramirez, a student at CMSD who has a summer internship with PCs for People, works to sort mice and other devices out of a bin in their warehouse.If the Internet were treated like a utility like water or electricity—funded by taxes and protected by further regulations—there wouldn’t be such a problem with a lack of access, advocates like Gordon argue.

CMSD responded to the issue by becoming an anchor for an innovative project that could change the landscape of Cleveland’s digital divide.

Announced earlier this year, CMSD hired Cleveland nonprofit DigitalC to extend high-speed internet services to thousands of CMSD families, targeting parts of the city where the digital divide is the worst.

The first goal, according to DigitalC CEO Dorothy Baunach, is to bring internet services through an innovative fixed-wireless system to 1,000 CMSD households before the school year starts (CMSD will pay about $192,000 for these families’ services while there are students in the household).

The mid-term goal is for 8,400 additional households to be connected by June 2021, with an eventual goal of connecting any remaining families by the 2022-2023 school year (potentially about 16,000-17,000 households).

“To get to those 16,000 households, the capacity of the full network will actually be around 27,000 households,” explains Baunach, noting that DigitalC will be able to serve non-student homes as well. “When the technology is headed into the neighborhood it doesn’t know who lives in the houses, it just knows if you can reach it or not.”

Access to free internet would be a game changer for many CMSD families, including those on a fixed income like Marsha Howard, 71. She is the sole caregiver for her grandson, who is an incoming CMSD fourth grader.

Howard says she was not sure how well her grandson will do with remote-only learning for an extended period of time, especially considering he has a Individualized Education Plan (IEP) because of his learning retention issues.

Additionally, the laptop Howard and her grandson received from the district last spring is old and doesn’t have the functionality to accomplish some of the tasks teachers asked them to do, she says.

“I don’t really see him doing very well without the help that the IEP is supposed to give him,” Howard says, noting that her grandson will still meet remotely with a special education instructor a few times a week.

“There are some kids that are just really, really into computers and internet and whatever, [but] he’s a more hands-on type of person,” says Howard of her grandson. “He likes to put things together, likes to figure things out with his hands.”

Gordon says his district provided 1,300 cameras to its intervention specialists to allow them to work remotely with children with IEPs; invested in tele-therapy systems; and is training teachers in working remotely students with IEPS.

Gordon says there is also a call-in or in-person help desk to help parents with technological problems.

Howard, who already pays for internet, says the district never offered her a Wi-Fi hotspot, despite her lack of income. Gordon says families who already have internet access weren’t offered hotspots—to triage those with the greatest need.

“We have a week planned for family-student parent-teacher conferences where we’ll be creating a care plan for each family, assessing their technology needs both for devices and access to high-speed internet,” Gordon explains.

A new model for connecting families

Angela Siefer, executive director with the National Digital Inclusion Alliance (NDIA), a Columbus-based nonprofit advocating for broadband access, says the main digital barrier for Cleveland families is the relative expense of internet services, rather than a lack of infrastructure to access those services.

“Poverty tracks closely with broadband adoption,” Siefer says.

PCs for People’s warehouse for devices that will be recycled or reused.NDIA in 2017 listed Cleveland as the fifth worst-connected city in the country, with almost 27% of all households without internet access.

PCs for People’s warehouse for devices that will be recycled or reused.NDIA in 2017 listed Cleveland as the fifth worst-connected city in the country, with almost 27% of all households without internet access.

DigitalC seeks to overcome that shortcoming by providing free service for CMSD families and low-cost service (about $20 per month, says Baunach)) for non-CMSD families. The average cost of high-speed internet is about $60 a month.

DigitalC has access to already-existing fiber (saving the financial physical challenges of adding new fiber), says Siefer, through a previous partnership with fiber company Everstream.

Baunach says DigitalC started its EmpowerCLE initiative to “connect the unconnected” back in 2016, and completed its first major project in 2018—connecting 550 families in three different Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority (CMHA) buildings with CMHA-subsidized internet services—giving residents access for $10 per-month.

DigitalC has continued to expand its mesh fixed-wireless system, which requires affixing signal transmitters to tall buildings to send signals to specific neighborhoods.

However, the organization has its work cut out for it as the school year rapidly approaches. DigitalC spokesperson Jim Kenny said that as of last Friday, Aug. 14, only 252 CMSD student households out of 1,000 were signed up for EmpowerCLE internet services.

What’s more, DigitalC and CMSD are still working on launching a fundraising campaign to build out the full network—an initiative that will cost at least $36 million.

Securing the devices

While DigitalC is scrambling to expand its network and get families signed up for services, PCs for People is similarly hustling to get its 10,000 laptops and other devices out to non-CMSD families.

PCs for People’s executive director Bryan Mauk says it’s a tall order to get that many devices out to students before school starts—especially with other school systems across the country also seeking devices.

Before the pandemic, the nonprofit would distribute 100 to 200 computers a month at low cost—$30 for a desktop and $50 for a laptop. When schools pivoted to online learning last spring, PCs for People started pushing out about 1,000 to 2,000 computers a month.

Now, it’s an all-out scramble to get out as many computers as possible, Mauk says. The organization is accepting donations of old computers and laptops, especially from the business community. Anyone interested in donating can call (216) 600-0014 or email PC for People.

Mauk says that while the county’s initiative will cover two of the most immediate needs—providing devices and hotspots—there’s a key third need.

“So, there’s the device and the connection, but then the third part is the ongoing support,” explains Mauk, adding that they offer one-year warranties (or three free repairs) and digital literacy classes.

Ashbury Senior Community Computer Center, CMHA, and the libraries also offer their own digital literacy classes.

Catherine Tkachyk, Cuyahoga County’s chief innovation and performance officer, says she knows the digital divide will persist, despite the current effort.

“These two years give us some runway to try to solve that problem that’s community-wide,” she says. “A long-term, sustainable solution—that’s really what we want to do. The digital divide didn’t show up with the pandemic and it’ll be there after the pandemic if we don’t make an effort as a community to change it.”

DigitalC is using former CMSD students to perform some of that outreach work as “brand ambassadors,” trying to get the word out to families about DigitalC’s internet services, Baunach said. They’ll be going door-to-door and trying to engage with CMSD families via social media, as well.

Baunach said it’s unfortunate that it's taken a pandemic to get people energized around the topic of expanding broadband access. Still, she’s hopeful for the future.

“Everybody now recognizes this problem; we don’t have to tell people the ‘why’ anymore, we just have to say, ‘we think we know how,’” she said. “And we pretty much believe we’re the ones on the ground and prepared to do this.”

Conor Morris is a corps member with Report for America. You can find him on Twitter at @condormorris, or email him at cmorris@advance-ohio.com. This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 16-plus Greater Cleveland news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland.