Organizations, congregations attempt to expand COVID-19 testing in poorer Cleveland neighborhoods

Do you think you need to get tested for COVID-19?

Here are a few ways to do it:

Hospitals and health systems:

Check their websites—they often have a hotline to call to explain their processes.

MetroHealth System has a hotline at (440) 92- 6843. Typically, you call and set up a time to talk to a doctor through a virtual meeting or a phone call. They question you, then greenlight you for testing (or not).

You go to a testing site location and get tested. Warning: While the test may be free, the doctor’s appointment might be billed to your insurance.

Federally qualified health centers:

Call your nearest community health center and say you’d like to get tested.

They will set-up an appointment with a doctor to screen you, and, according to Eric Morse, CEO of Circle Health, will likely greenlight you to get tested regardless of your symptoms.

You go to a testing site at the health center and get tested. Some of these health centers, like Care Alliance, do have free drop-in testing hours where you don’t need an appointment.

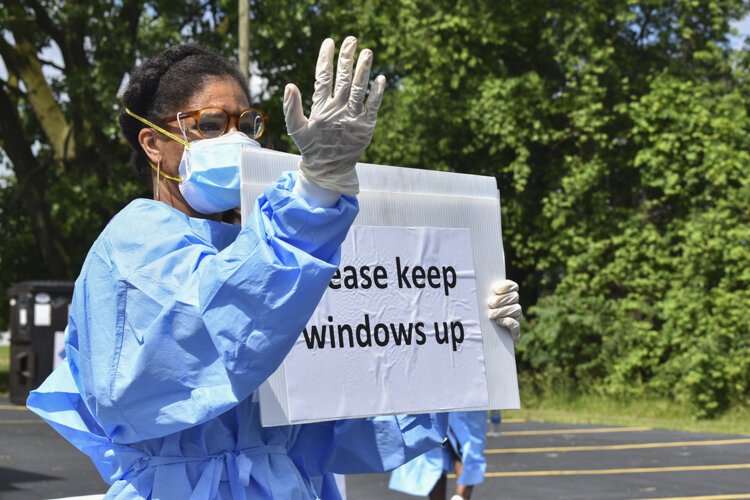

On a hot day in early June, Dr. Heidi Gullett, medical director at the Cuyahoga County Board of Health (CCBH), stood with a host of other public health workers in protective gear in the parking lot of the Word Church at 5900 Kinsman Road.

She watched a man ride his bike into the lot, up to one of three lanes set up for cars to drive through. CCBH and MetroHealth System worked with church officials to create a pop-up COVID-19 testing site in the church parking lot.

Dr. Heidi Gullett, center, Cuyahoga County Board of Health’s medical director, explains the process to a driver who came through a pop-up COVID-19 testing site located at the Word Church on Kinsman Road in Cleveland back in early June.“He was on his way to work at a construction site,” Gullett says of the patient. “He had a cough and just said, ‘I really want to be tested.’”

Dr. Heidi Gullett, center, Cuyahoga County Board of Health’s medical director, explains the process to a driver who came through a pop-up COVID-19 testing site located at the Word Church on Kinsman Road in Cleveland back in early June.“He was on his way to work at a construction site,” Gullett says of the patient. “He had a cough and just said, ‘I really want to be tested.’”

After a quick screening using the standard nasal swabs, the man was back on his way to work within five minutes.

This is just a snapshot of the work that the CCBH and MetroHealth have been doing since mid-May when they started an initiative to launch testing sites in key neighborhood locations throughout the region.

Community health centers like Care Alliance in Cleveland’s Central neighborhood have also started sites where anyone can drop in to get tested.

More test sites are on the way.

Between mid-May and the end of June, CCBH and MetroHealth tested more than 3,500 people at sites like the Word Church through a county-funded partnership.

According to a CCBH spokesperson, 39% of the clients, like the bike rider, identify as Black or African American.

Setting up a testing site accessible to Black Ohioans is critical in a state where 27% of all COVID-19 cases are in African Americans—despite making up about 13% of the total population, according to Ohio Department of Health data.

Nichelle Shaw, a supervisor in prevention and wellness with CCBH, explained that her organization tries to look at where cases are spiking in Cuyahoga County when they set up a new testing site. Those locations include homeless shelters, nursing homes and other congregant living facilities.

“That’s in addition to looking at other factors, such as certain social determinants of health, [or] if a community has a high infant mortality rate, for example,” Shaw explains.

That’s why partnering with “trusted community organizations” to locate testing sites at places like the Word Church is key, Gullett says, because they can help get the word out about testing.

Ramping up

A local collective of churches called the Greater Cleveland Congregations (GCC) has partnered with CCBH on its Color of Health initiative, in which the GCC’s 17 member churches will serve as testing sites and use their platforms to disseminate information.

The county isn’t alone in trying to make tests available to people who live in high-risk neighborhoods. Another source of Cleveland testing sites is through federally qualified health centers, which operate in under-served neighborhoods.

The centers are working together to ramp up access to testing, with some offering free walk-up and drive-up testing hours each week. Eric Morse, CEO of the Centers for Families and Children and Circle Health Services, says the goal of that collaboration is to eventually do upward of 300 to 400 free tests per day at various qualified centers.

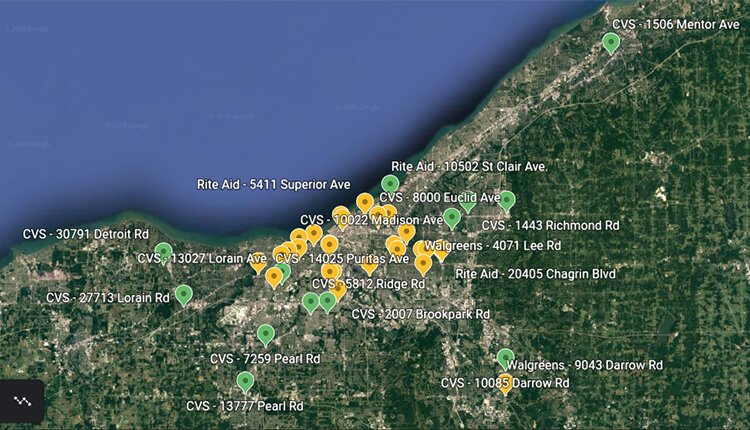

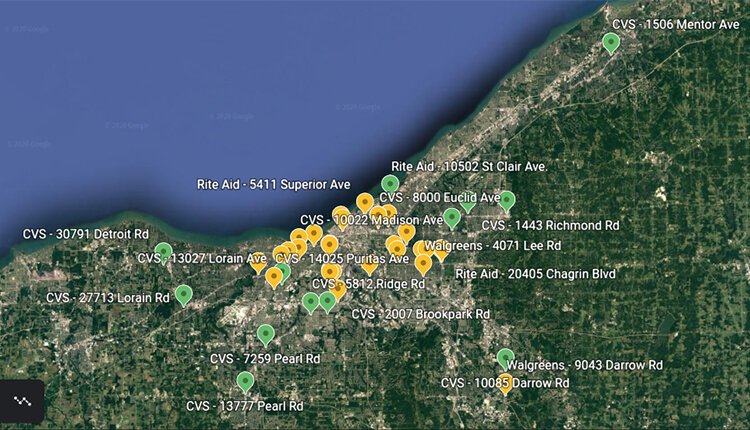

Locations of 35-plus Rite Aid, Walgreens and CVS pharmacies throughout the Cleveland area. The pharmacies labeled in yellow do not offer COVID-19 testing as of early July; the stores labeled in green do.

Locations of 35-plus Rite Aid, Walgreens and CVS pharmacies throughout the Cleveland area. The pharmacies labeled in yellow do not offer COVID-19 testing as of early July; the stores labeled in green do.

For example, Care Alliance, one of the federally qualified centers, has been offering a free drive-up and walk-in COVID-19 testing clinic on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays each week since mid-June.

Dr. Claude Jones, CEO of Care Alliance, says his agency has done 300 tests as of last Monday, July 6, with 11 confirmed positives.

“The majority of those [positive] individuals were asymptomatic, so we’re catching those carriers,” Jones says, noting that these were people who might not be tested otherwise.

These neighborhood sites have made it easier in recent weeks to get a coronavirus test in Ohio, but barriers remain—especially for poor people or others who might not have health insurance, a regular doctor, or access to a car or public transportation.

Dr. Charles Modlin, a doctor with the Cleveland Clinic and chair of the Ohio Minority Health Strike Force’s outreach committee, said that the strike force is in the process of finalizing its recommendations to the state for how to address the virus’s disproportionate impact on people of color.

Modlin says recommendations will include more pop-up testing sites close to minority neighborhoods, including Cleveland. However, he says state-run pop-up sites have yet to start Cuyahoga County.

Ohio isn’t the only state struggling to improve access to testing in high-risk neighborhoods. It’s a national problem. Dr. Jennifer Nuzzo, lead epidemiologist for the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Testing Insights Initiative, says she’s not aware of any gold-standard model for improving access to testing in the U.S.

Nuzzo says access to transportation is a big barrier for poor communities, so some cities have created mobile testing clinics to meet people where they are.

She stressed that while pop-up testing sites help expand access, but they’re not a permanent solution.

Redlining access

The difficulty in getting a COVID-19 test in poor communities didn’t sit well with GCC.

It recently called on major pharmacies, such as CVS, Rite Aid and Walgreens, to expand their COVID-19 testing sites in inner-city Cleveland after finding that most of the stores didn’t offer testing in poor neighborhoods.

An analysis by the GCC found that of the 35-plus CVS, Rite Aids, and Walgreens in the Cleveland area, the only pharmacies that offer testing are at the edge of, or beyond, the city limits.

Dr. Heidi Gullett, left, Cuyahoga County Board of Health’s medical director, explains the process to a driver who came through a pop-up COVID-19 testing site at the Word Church on Kinsman Road in Cleveland back in early June.Pastors for GCC alleged during a Thursday, July 9 press conference that this lack of access to testing in neighborhoods that are primarily African American is a product of structural racism, akin to “redlining” access to testing.

Dr. Heidi Gullett, left, Cuyahoga County Board of Health’s medical director, explains the process to a driver who came through a pop-up COVID-19 testing site at the Word Church on Kinsman Road in Cleveland back in early June.Pastors for GCC alleged during a Thursday, July 9 press conference that this lack of access to testing in neighborhoods that are primarily African American is a product of structural racism, akin to “redlining” access to testing.

Rev. Ronald Maxwell, senior pastor of Affinity Missionary Baptist Church (a GCC member), said that in the last week alone that he’s heard from three congregation members who could not get a coronavirus test in a timely manner.

“That’s not simply because of the barriers that are put up toward testing—and those barriers are many—each of them had to leave not just their neighborhood but drive through the suburbs into the exurbs,” Maxwell says.

There are early signs that the GCC’s advocacy is working. CVS spokesperson Mike DeAngelis said last Friday, July 10 that CVS was committing to putting four new store-based testing sites in the city of Cleveland by July 24, “to serve highly vulnerable communities as determined by the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index.”

Conor Morris is a corps member with Report for America. You can find him on Twitter at @condormorris, or email him at cmorris@advance-ohio.com. This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 16-plus Greater Cleveland news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland.