Code Name Hope: Cozad-Bates house takes its place in history with virtual opening

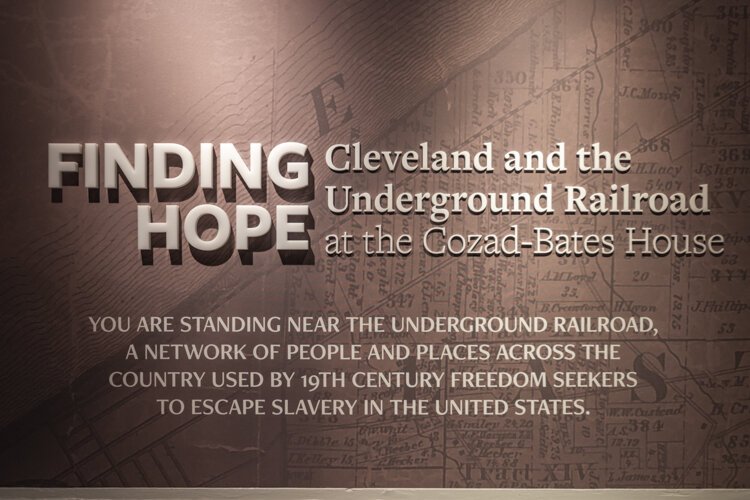

Nearly 155 years after the 13th Amendment was ratified and slavery abolished in the United States, a 167-year-old tribute to the Clevelanders who worked to harbor former slaves and ensure their paths to freedom, officially made its debut in University Circle yesterday, Monday, Nov. 16.

The 1853 Cozad-Bates house—the only pre-Civil war house in University Circle—officially became the Cozad-Bates House Interpretive Center at 11508 Mayfield Road, with the help of partners Restore Cleveland Hope, Cleveland Restoration Society, Western Reserve Historical Society, and Cleveland Ward 9 City Council Member Kevin Conwell.

“This is a story about the courage of freedom seekers,” says Chris Ronayne, executive director of University Circle Inc. (UCI).

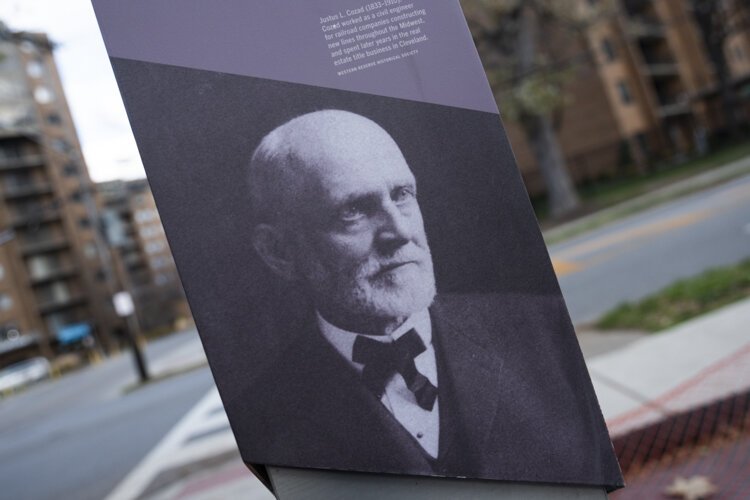

Cleveland Foundation Room in the Cozad Bates HouseIn the 1800s, Andrew and Justus Cozad were known to be against slavery along with other neighbors in East Cleveland Township, what we now call University Circle. There were also many Underground Railroad activists in this area, including their neighbor, Horace Ford, says Ronayne, who adds that along with Ohio City’s St. John’s Episcopal Church went under the code name “Station Hope” for former slaves on their way to Canada—and freedom. Cleveland itself was known simply as "Hope."

Cleveland Foundation Room in the Cozad Bates HouseIn the 1800s, Andrew and Justus Cozad were known to be against slavery along with other neighbors in East Cleveland Township, what we now call University Circle. There were also many Underground Railroad activists in this area, including their neighbor, Horace Ford, says Ronayne, who adds that along with Ohio City’s St. John’s Episcopal Church went under the code name “Station Hope” for former slaves on their way to Canada—and freedom. Cleveland itself was known simply as "Hope."

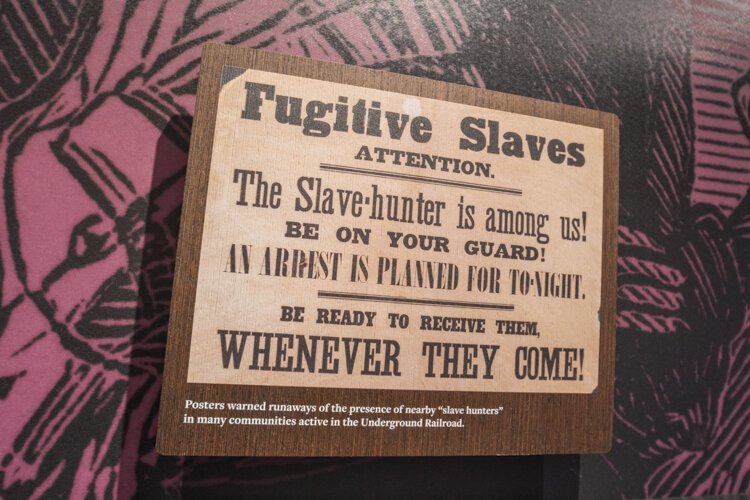

"We unfortunately don’t know many details about how many former slaves passed through Cleveland," says Ronayne. "We do know that the free black population in the City of Cleveland numbered only 799 of 43,417 total residents in 1860. This could both be tied to the legacy of Ohio’s Black Laws, which limited black freedoms here, and also that due to the Fugitive Slave Laws, no freedom seeker was safe from capture and re-enslavement anywhere in the United States, including in the North."

The only true freedom existed in Canada, explains Ronayne, and many freedom seekers settled in St. Catherines, Ontario.

"In the exhibits, we do have a Quarterly Report of Cleveland’s Underground Railroad, published in a January 1855 edition of Frederick Douglass’ Paper, which states 'That the condition of the Road is excellent' with 275 passengers who made their way to Canada over the past eight months."

While Ronayne points out that there is not much known about Cleveland’s role in the Underground Railroad, it is known that the city and surrounding area—and Lake Erie—did play a role and had many abolitionists and activists.

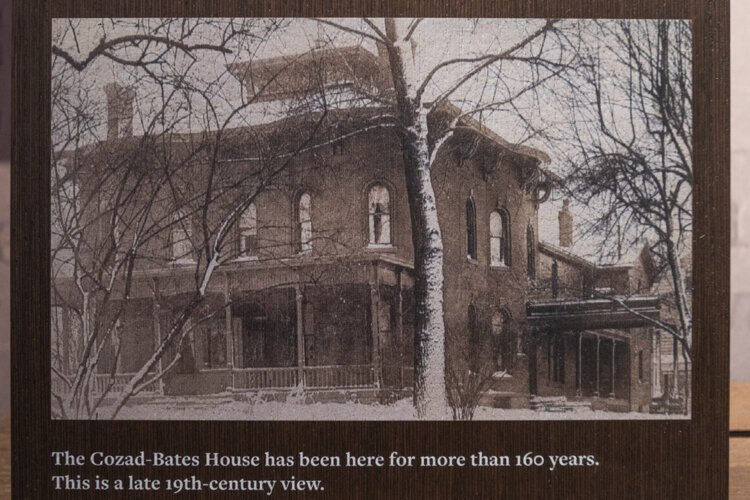

The Cozad-Bates house itself was built in what was East Cleveland Township (the University Circle area had not yet been annexed into Cleveland) in at least three phases, with the original middle house being constructed in 1853, says Ronayne. Additions were made in the 1860s, and the final, Italianate-style portion of the house on Mayfield Road was erected in 1872.

The original structure was built by Andrew Cozad for Justus, using brick from Andrew’s brickyard. Justus oversaw later additions to the house for his growing family, which included his daughter Olive, who married Theodore Bates and the two purchased the home in 1890.

The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. Owned by University Hospitals, the house sat vacant for decades. “It was in danger of the wrecking ball in 2006 when it was landmarked by the City of Cleveland,” says Ronayne. “University Hospitals offered it to University Circle in 2006 and in 2007 we got to work on raising funds.”

Today’s house comprises 6,000 square feet, with 1,000 square feet making up the Interpretive Center. The Interpretive Center was unveiled during a virtual Facebook tour on Thursday, Nov. 12—showcasing the house that stands as an enduring legacy to the networks of people who worked together against an unjust system of slavery.

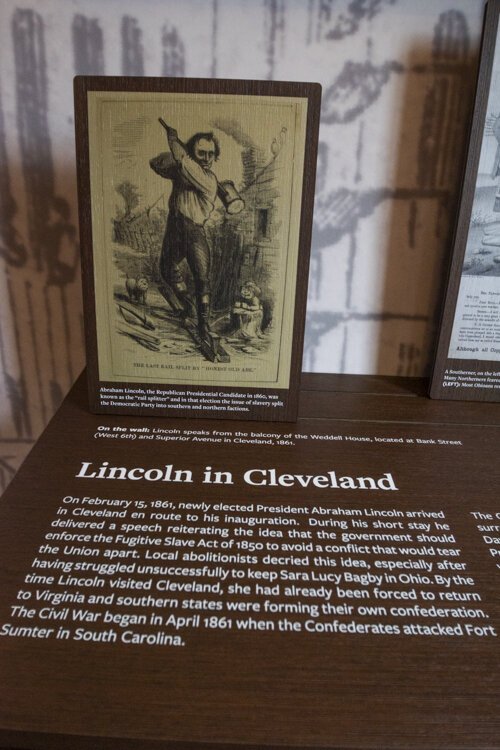

Abraham Lincoln display in the Cozad Bates HouseThe $2 million first phase includes a $500,000 roof, as well as repairs and renovations, and the creation of three indoor spaces and an outdoor exhibit area that highlight Cleveland’s history as a center of anti-slavery activism and honoring freedom seekers.

Abraham Lincoln display in the Cozad Bates HouseThe $2 million first phase includes a $500,000 roof, as well as repairs and renovations, and the creation of three indoor spaces and an outdoor exhibit area that highlight Cleveland’s history as a center of anti-slavery activism and honoring freedom seekers.

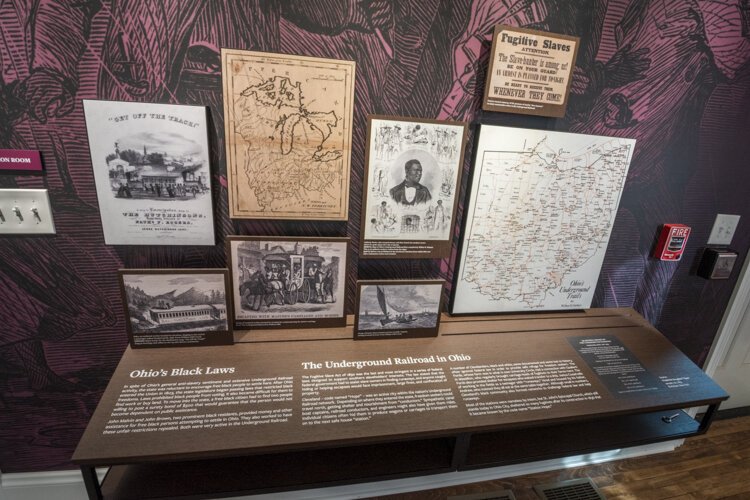

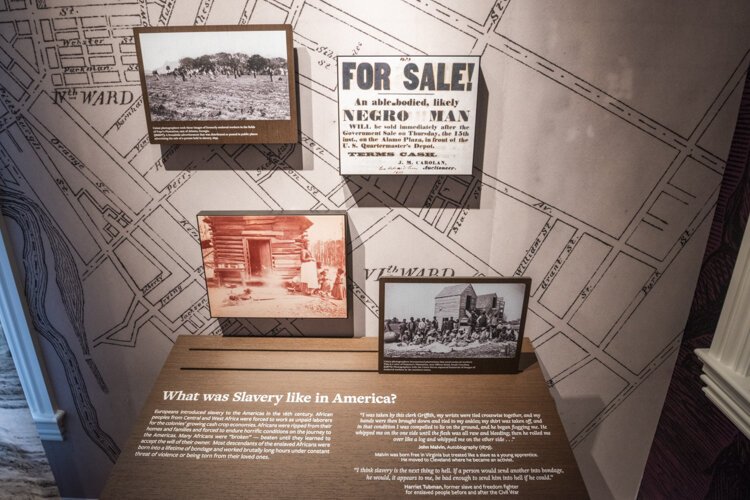

The Cleveland Foundation Room in the East Wing sets both the national and local context for slavery in the years leading up to the Civil War by highlighting stories of local anti-slavery activists and freedom seekers. One example is Sarah Lucy Bagby Johnson, a Cleveland resident who escaped slavery only to be returned to Virginia under the Fugitive Slave Act.

“Fortunately, West Virginia seceded from Virginia and became a free state,” says Ronayne. She returned to Cleveland, where she remained until her death.

The East Wing is decorated with Cleveland street maps that point out safe harbor houses around the city.

The West Wing in the Gund Foundation Room tells the story of the Underground Railroad and anti-slavery activism in the region. The exhibit lists East Cleveland Township residents who were active in the fight against slavery.

The KeyBank Community Room connects the past to the present with programming that outlines how the impacts of slavery are still seen in today’s social issues through an exploration of the 13th,14th, and 15th amendments developed by Case Western Reserve University’s Social Justice Institute. The Community Room also provides a space for small group discussions and programming led by docents and community partners. Throughout the space, guests may notice that special care has been taken to preserve the home’s remaining historic features and to make unique additions that tie to the exhibit narrative.

Joan Evelyn Southgate plaque dedication at the Cozad Bates HouseThe outdoor area includes an “equity table,” a plaque depicting the North Star—Ronayne notes the North Star and the Big and Little Dipper would have guided people on their paths to Canada—and the Joan Evelyn Southgate Walk, honoring the Cleveland woman who walked a 519-mile Underground Railway path from Ripley, Ohio to St. Catherines, Ontario.

Joan Evelyn Southgate plaque dedication at the Cozad Bates HouseThe outdoor area includes an “equity table,” a plaque depicting the North Star—Ronayne notes the North Star and the Big and Little Dipper would have guided people on their paths to Canada—and the Joan Evelyn Southgate Walk, honoring the Cleveland woman who walked a 519-mile Underground Railway path from Ripley, Ohio to St. Catherines, Ontario.

Southgate made her historic walk in 2003, at the age of 73. She was inducted into the Ohio Civil Rights Hall of Fame in 2014, and was present at the Cozad-Bates Interpretive Center during Monday’s debut.

“Today was Joan’s first visit to the completed site and we thought it a good day to unveil the recognition of Joan Evelyn Southgate Walk,” says Ronayne. “It was a surprise to her. She was overjoyed, and we were thrilled to celebrate this moment with her.”

The center will open to in-person visitors in 2021. For now, with the coronavirus pandemic, even the outdoor areas will remain closed to the public. But Ronayne says the outdoor area will be open soon.

“We are still finishing up a few construction items, so the outdoor site is not yet open to the public,” he says, “but we expect to take down the construction fence by year’s end to welcome all to the exterior grounds and open the interior when safe (health) conditions make it appropriate.”

Ronayne says plans for a $2 million phase two plan for the center include additional community, dining, and living space, and possibly seven bedroom suites on the second floor. He says UCI is in conversations with the Transplant House of Cleveland as a possible tenant, for guests who face long-term stays in Cleveland following organ transplants and follow-up care. However, the project is currently on hold, because of the pandemic.

LDA Architects served as lead architect and the exhibit design team comprised Möbius Grey LLC, heyhey, and Communication Exhibits Inc.; RW Clark Co. served as general contractor for the interior while R.J. Platten as general contractor for the exterior. DERU Landscape Architecture and Agnes Studio designed the exterior and wayfinding.

Additional support for the renovation and restoration of the Cozad-Bates House came from the State of Ohio, Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District, the Abington Foundation, the Louise H. and David S. Ingalls Foundation, Ohio and Erie Canalway, the David and Inez Myers Foundation, Nathan & Fannye Shafran Foundation, and Cuyahoga County.