Eastside Greenway envisions future connections

This summer, eighteen far-flung east side suburbs and the City of Cleveland took significant steps toward making the Eastside Greenway a reality.

With the completion of a substantial 102-page master plan, the municipalities are now moving from the planning phase to the implementation phase of the project.

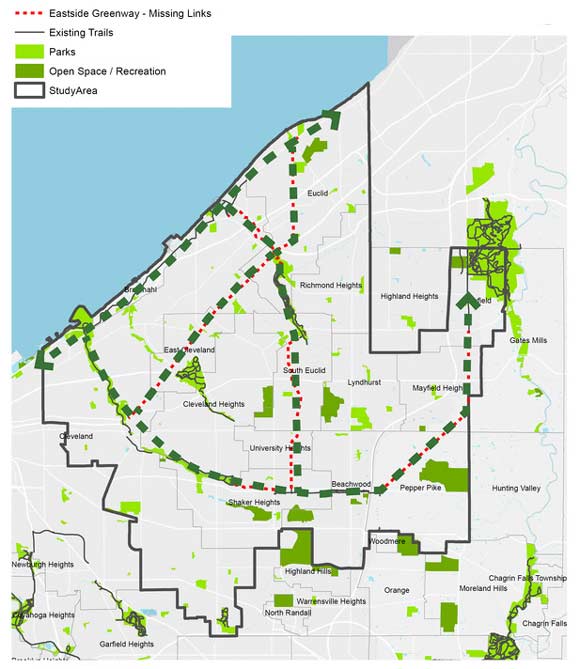

The Eastside Greenway, in the works since about 2013, is a series of interconnected paths and trails that link the suburbs to each other; to Cleveland; to transportation corridors like the rapid line and the Opportunity Corridor; and to amenities like Lake Erie.

Make no mistake: The Eastside Greenway could transform Cleveland’s east side as we know it by creating attractive alternatives to driving. The plan is all about resetting the default mode of transportation from car-oriented to car-inclusive -- meaning we start thinking about getting around both with and without our cars.

Remember, we’re trying to overcome a 50-plus-year-old tradition the car as the only mode of transportation. That’s not easy.

“This Master Plan offers a lot of recommendations,” says Nancy Boylan, project director for LAND studio, a key driver of the Greenway. “But ultimately each municipality has to adopt this plan. And because there are 19 [municipalities], it’s going to take some time. Each municipality has to design and implement the path that works for them, work out the funding, and figure out where they are in scheduling resurfacing these stretches.”

In addition to the municipalities, there are many entities involved in the Eastside Greenway. Overseeing the study was the Cuyahoga County Planning Commission, LAND Studio, the Cleveland office of Parsons Brinckerhoff, volunteers from the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT), the Cleveland Metroparks, and council members from many participating suburbs.

Funding for the $150,000 study came from the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA), under the Transportation for Livable Communities Initiative (TLCI). NOACA provided a grant of $118,000 that was supplemented by $32,000 from the Cleveland Foundation, Eaton Corporation and the Metroparks.

At a meeting this past July at John Carroll University, representatives from SmithGroup JJR, who authored the study, presented their exhaustive methodology. The report catalogues an enormous number of geographical factors throughout the eastern suburbs -- from the size and location of green spaces to population density, to current commuter routes.

The planners also worked on route priority, which was determined by public input through a series of public meetings in 2015 as well as an online survey late last year.

Representatives from SmithGroupJJR and Parsons Brinckerhoff leveled with the participants at the JCU meeting: “This is never going to happen at once. This plan is data driven, but community led.”

In other words, it’s best to think about incorporating greener methods of moving around the east side now; start thinking about what can be accomplished in one year, in five, in ten years. That way, in ten years we don’t have a dusty old plan, but rather a good start towards a vibrant and interconnected series of greenways for generations to come.

The very diversity of the municipalities demands an approach that’s both practical and creative. “There are so many varying options,” Boylan says. “We can’t take a cookie cutter to the Greenway or expect to create the same thing everywhere – each section doesn’t allow for that. It comes down to how much space we have. Creating part of the network can be an simple as adding a sharrow, but then also as complicated as building an entirely new multi-use path on the side of the road, like what you might see in the Metroparks.”

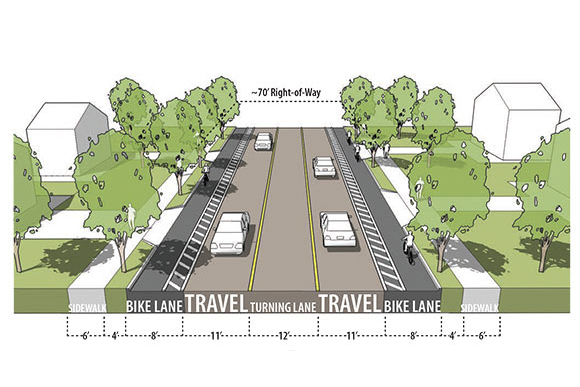

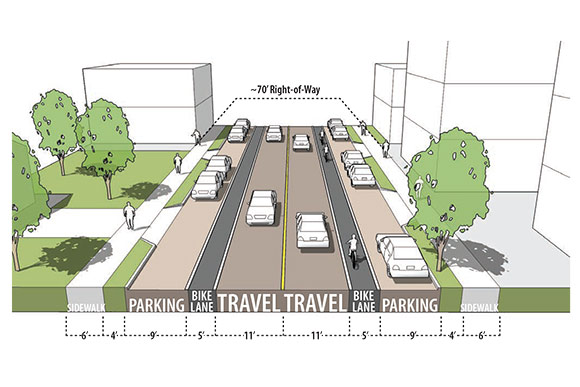

Here’s an example of how the Greenway could develop: Noble Road, which runs from Euclid Avenue to Mayfield Road, through Cleveland Heights and East Cleveland, is considered a high priority link. The proposal for the retail portion of this corridor is to change it from four lanes – two northbound, two southbound, with some on-street parking – to a corridor that accommodates sidewalks, a parking lane, bike lane and two travel lanes for cars. The entire corridor, at just about 70 feet wide, would remain the same size, but would be reconfigured to allow for cars and pedestrians as well as bikes.

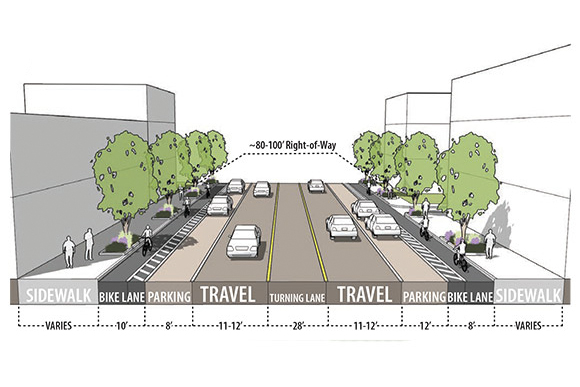

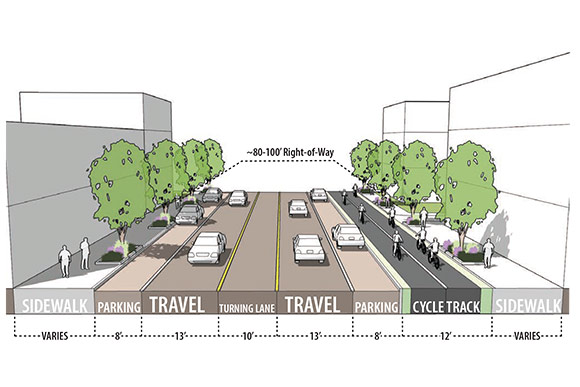

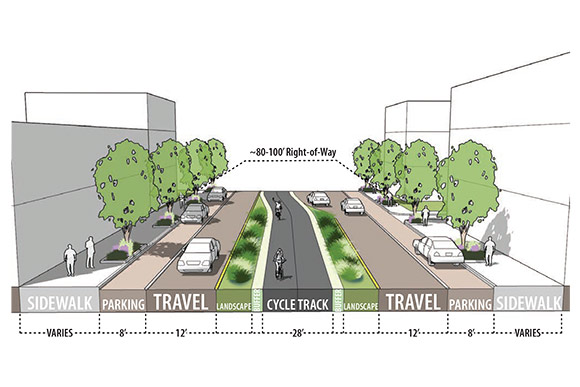

Another section of the Eastside Greenway involves Euclid Avenue from MLK Drive in University Circle to East 222nd, a seven-mile route through Cleveland, East Cleveland and Euclid. The whole corridor is 80 to 100 feet wide, but it is underused as a throughway, since, according to the master plan, it “passes through highly challenged portions of Cleveland and East Cleveland where infrastructure investments are needed to enhance the aesthetics, safety and mobility options for travelers.”

The project's master plan suggests that Euclid would be ideal for a “road diet,” which would shrink the five lanes for cars to make room for pedestrian and buffered bike transit lanes. The master plan also offers this vision: “Improvements in Euclid Avenue are also an opportunity to support economic development and reinvestment in adjacent commercial and residential lands, which have seen decades of disinvestment.”

In other words, with transit and pedestrians comes investment in the buildings lining Euclid Avenue, similar to the way the RTA Silver Line helped to turn the fortune of Euclid Avenue in Mid-Town. These are just two portions of a very ambitious plan to connect the entire east side.

At the JCU meeting, Glenn Coyne, executive director of the County Planning Commission, stated that his team and LAND studio would continue to spearhead the project. “People way above my pay grade are very interested in this project, and the interest it generates from the general public,” Coyne said. But he also pointed out that the planning commission cannot tell cities what to do, or how to allocate funds.

“The adoption agreement has been well-received, and people on the steering committee – many of them are city council representatives,” Boylan says. “We need everyone to be on board – the mayors, council, and citizens so these plans don’t sit on a shelf collecting dust, but become a reality.

“These trails are for more than just cycling and walking,” Boylan adds. “These trails will provide individuals with connections for work, the store, the doctor, or to RTA. It’s not cycling and walking to walk, it’s transit."