Federal aid arrives for low-income residents’ water and sewer bills

Low-income Cuyahoga County residents who need help with their water and sewer bills may benefit from a new federal emergency program called the Low-Income Water Assistance Program (LIHWAP).

CHN Housing Partners, the Cleveland agency that administers the program along with most other local utility affordability programs, will be accepting applications from residents until Sep. 30.

Cleveland Water Department building on Lakeside Avenue in ClevelandThe maximum one-time aid a household can receive through LIHWAP is $750, although “the amount may vary depending on the need of the household,” says Megan Nagy, a spokesperson for the Ohio Department of Development (which developed the state’s rules for LIHWAP).

Cleveland Water Department building on Lakeside Avenue in ClevelandThe maximum one-time aid a household can receive through LIHWAP is $750, although “the amount may vary depending on the need of the household,” says Megan Nagy, a spokesperson for the Ohio Department of Development (which developed the state’s rules for LIHWAP).

Here are some basics on the program, according to a press release from CHN:

- It’s available to Cuyahoga County residents who live at or below 175% of the federal poverty guideline (for a family of four, their annual income must be at or below $46,375).

- Applicants must pay their own water and sewer bills, and their bills must be in their own name, not the landlord’s name.

- To apply, you can call (216) 350-8008 to make an appointment or make an appointment online. Appointments are only available by phone or video conference.

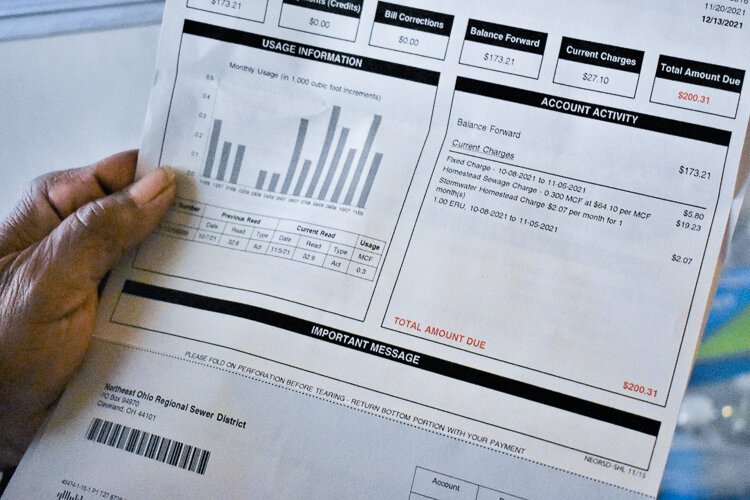

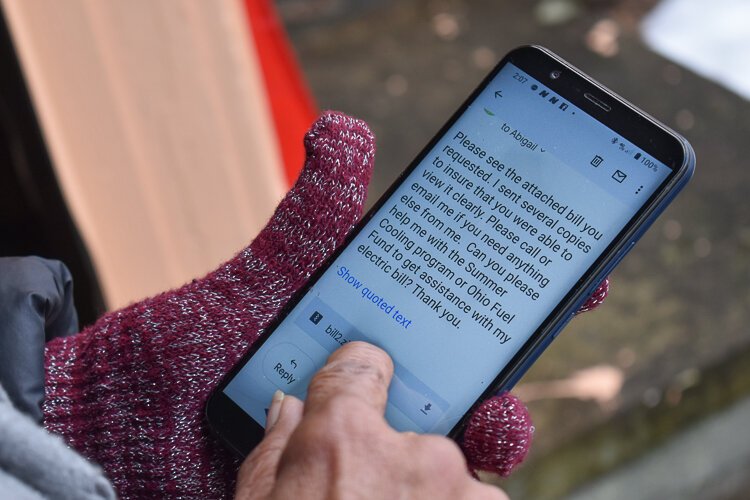

- You should be prepared to provide multiple documents at least three days before the appointment visit, including: your most recent sewer/water bills; photo ID; social security cards and birth certificates (or other proof of legal residency) for all household members; and paystubs or other income verification for each household member over the age of 18.

- The aid goes directly to your utility provider. CHN spokesperson Laura Boustani says those facing a disconnection will often have that process halted as long as they have an appointment coming up with CHN and their utility provider is in contact with CHN.

- Boustani said it’s not clear yet how long the wait time is between application and appointment, considering this is a new program.

Laura Boustani, a spokesperson for CHN, says people will be applying for the LIHWAP funds through the same portal people use to apply for the federal HEAP (Home Energy Assistance Program) and PIPP (Percentage of Income Payment Plan) programs.

As the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative (NEO SoJo) has previously reported, it can be difficult for people to get an appointment through that portal, with applicants often finding there are no appointments available. Boustani said people should call in early in the day and at the top of each hour to find new appointment slots open.

Boustani says her agency brought concerns about this issue to the Ohio Department of Development last year and was allotted more funding to increase staffing to reduce wait times. However, this problem appears to persist.

LIHWAP was part of the December 2020 stimulus bill passed in Congress. The American Rescue Plan passed by Congress in early 2020 added additional money to the program, for a total of $1.1 billion split among states and tribal territories. Ohio received $43 million, Nagy says.

Manny Teodoro, an associate professor of public affairs at the University of Wisconsin-MadisonIt’s not yet clear how much impact the program will have, said Manny Teodoro, an associate professor of public affairs at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Teodoro has researched water and sewer equity and affordability programs for more than a decade, and works directly as a consultant with some cities’ utility departments.

Manny Teodoro, an associate professor of public affairs at the University of Wisconsin-MadisonIt’s not yet clear how much impact the program will have, said Manny Teodoro, an associate professor of public affairs at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Teodoro has researched water and sewer equity and affordability programs for more than a decade, and works directly as a consultant with some cities’ utility departments.

Teodoro says there are often serious limits to programs like LIHWAP, although he did note this is the first time the federal government has offered an assistance program of this kind for water and sewer bills.

“Any assistance program, whether it’s local, state or national, can only ever be one small but important part of an overall affordability strategy,” he says. “And that’s just because of the inherent limits to income-qualified assistance.”

Each individual state must figure out how it will administer the program, Teodoro says, which can be costly and time-consuming; that’s partly why many states have not gotten the program up and running until recently. The other major cost to consider is the time and effort put in by the people the program is meant to help.

Most utility assistance programs require a lot of documentation and have a lengthy application process, which creates what Teodoro called an “administrative burden” for the applicant; LIHWAP is no different. Teodoro notes that HEAP, the program LIHWAP is based on, historically boasts a dismal participation rate of about 16%, partly for this reason.

Another important thing to note is that many apartment complexes do not have individual water meters for each unit, Teodoro says. That prevents a potentially large percentage of low-income people from receiving the assistance because they do not have water or sewer bills in their name.

This story is a part of the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative’s Making Ends Meet project, and a continuing effort to report on the burden of water bills on low-income Clevelanders. NEO SoJo is composed of 18-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater. Email Conor Morris at cmorris40@gmail.com.