Five old school places that rock the Rust Belt

The Cleveland renaissance is characterized by art galleries and studios blooming in our vintage industrial buildings. Mixed-use development is spreading like wildfire from Hingetown to Shaker Heights and beyond. Millennials are flocking to the sleek new bars and eateries on the East Bank of the Flats.

But there are places where the Cleveland of yesteryear persists. In them you'll find hulking machinery, lengths of herculean chain forged to moor the freighters of the Great Lakes and plenty of steel: steel bridges, steel anvils, even sparks of steel. In this roundup, Fresh Water visits five such local spots that transport you back to the Rust Belt's hey day.

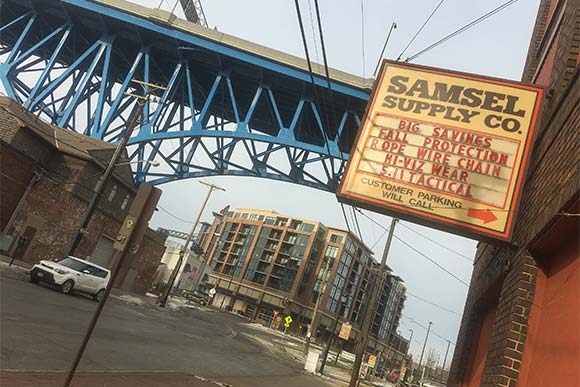

Samsel Supply, 1235 Old River Road

Step into Samsel Supply and you'll find yourself amid displays of giant ropes and chains that will ultimately festoon industrial vessels such as the Olive L. Moore and Pere Marquette 41. The iconic store is where working women and men go to outfit the grand dames of the Great Lakes and themselves, with heavy coveralls and thick rubber boots that mean business.

Launched in 1958 by Frank Samsel, the humble beginnings quickly grew into a major source for construction, industrial and maritime supplies throughout the region. The store is still owned and operated by the Samsel family, including Frank's son Mike and his sister Kathy Petrick, who are in ongoing development talks regarding a host of vintage buildings along the historic stretch of Old River Road.

Need another reason to love Samsel Supply? Frank Samsel was instrumental in the clean up of the once-deemed "dead" Cuyahoga River. He did it aboard a very special vessel named the Putzfrau, which tackled unimaginable contaminations of oil, chemicals and "huge black blobs."

The family continues to build on Frank's groundbreaking environmental efforts by partnering with the county in the Greenspace Initiative Program, which aims to restore and protect waterways and riparian areas amid other goals.

In the meantime, if you need a boom pendant thimble, a couple hundred feet of high test steel chain or a male jaw and ball bearing swivel becket, Samsel's got you covered.

HGR Industrial Surplus, 20001 Euclid Avenue

HGR is one of those places you pass a hundred times and never really see. The sprawling facility is unremarkable at first blush, just another low-slung building facing an asphalt parking lot full up with pickups and flatbeds.

Old time Clevelanders, however, know the giant structure housed GM's Euclid Fisher Body Plant from 1948 to 1993. Among other things, bodies for iconic cars such as the El Camino, Toronado, Riviera and Cadillac Eldorado were manufactured here, but the site's history goes back to the late 1800s. What was once farmland became the subject of a long and contentious legal battle over zoning that ended up before the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS).

On November 22, 1926, the SCOTUS ruled on Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., in favor of the Village. The landmark case made headlines across the country as a definitive decision that enabled fledgling zoning laws. In 1942, however, Uncle Sam had a different vision for the 65-acre plot and usurped control of the site, announcing plans for a $20 million war plant despite protestations from residents and village officials.

What Uncle Sam wants, Uncle Sam gets, and the expansive plant was built. It originally housed Cleveland Pneumatic Aerol, which manufactured landing gear and rocket shells for about two years until Victory Over Japan Day marked the end of the WWII on September 2, 1945.

20001 Euclid essentially lay fallow until GM bought it in '48.

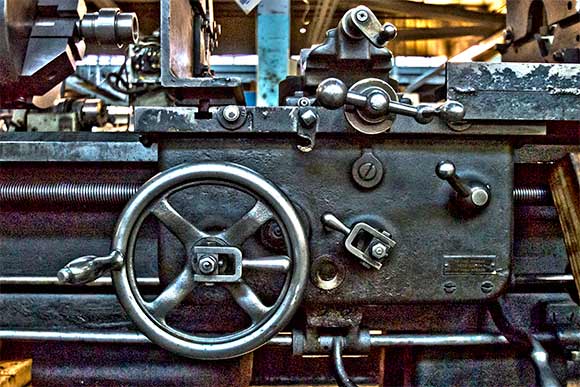

After the last GM worker left more than 20 years ago, the structure housed any number of tenants including HGR, which purchased the building last year. Stepping inside the 13-acre building is a singular experience. Here you will find the machines that threaded, milled and crimped when the Rust Belt was at its grittiest. Behold the remnants of what fueled every tool and die man for the last 100 years: a 38,000-pound press brake keeps watch over rows of table saws, while giant industrial robots await orders and a massive turret lathe, manufactured before you were born – just eight miles away at the Warner & Swasey factory on Carnegie, sits like a vigilant soldier.

Best of all, from the riveted wood beams to the clerestory windows overhead, the historic structure looks just as it did on the day this former WWII bomber plant opened more than seven decades ago.

Scranton Flats, 1851 Scranton Road

This length of trail quietly showcases Cleveland's bridges with one breathtaking vista after another. The spans over this section of the Cuyahoga represent more than a century of bridge technology. Their graceful arches fill locals with sighs, while the massive lift bridges are like steel dinosaurs with giant counterweights instead of jaws. And while much of the historic industry that populated Scranton Flats is long gone, the trail associated with it allows those who walk or bike this short stretch to get up close and personal to some of Cleveland's most lofty spans, which allow automobiles, pedestrians and cyclists to traverse their lengths while freighters, tugs and sporting vessels navigate the Crooked River below.

For the bridge-curious among us, Fresh Water suggests the following route: Start on the all-purpose trail that hugs the river along Scranton Road (full title: Cleveland Foundation Centennial Lake Link Trail). Head south, up the incline, while you take in the 1957 Norfolk Southern Cuyahoga River Bridge to your left. Go right at the fork in the trail and over the two pedestrian bridges, which were constructed in 2015 and give you a completely unique view of the 1927 Hope Memorial Bridge with its beloved Guardians of Transportation. When you reach the trail's end at the intersection of Franklin Avenue and Columbus Road, turn right and walk over the 1940 Columbus Road Bridge (you might have to wait if the bridge is up in order to let the likes of the 634-foot Great Republic pass through with her load of iron ore).

Continue north on Columbus – but do stop en route and tip your hat to the Flats Industrial Railroad Bridge, which is frozen in its highest position – and take a right when you get to Center Street, but not before you glance left and nod to the 1901 Center Street Swing Bridge down the way. Go on up the hill and take another right to head over the 1939 Carter Road Bridge. Then go left toward the defunct Eagle Avenue Viaduct (the green bridge next to the Cleveland Fire Station 21, which was built in 1923 and is home to the Anthony J Celebrezze fireboat).

There is something haunting about that abandoned intersection of Eagle Avenue and Carter Road, with that motionless old lift bridge looming. Now place your hands upon its steel and feel the energy and experience of this sentinel, which watched on silently as so many other bridges rose up around it over the past 93 years, including the George V. Voinovich Innerbelt Bridges that opened to the public just months ago.

You ought to be at the northern tip of Scranton Flats, which is where you – and much of Cleveland's history – started.

Rose Iron Works, 1536 East 43rd Street

Most every Clevelander has seen one particular offering from Rose Iron Works. While soon to be on loan to the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, the "Muse with Violin" screen is usually on display in the contemporary galleries at the Cleveland Museum of Art. While that graceful example of art deco metalwork has a fascinating history, 'tis the forge at Rose that uniquely evokes the Rust Belt – for here you will find the smiths.

Yes, those kinds of smiths – blacksmiths.

These are the craftsmen who manipulate steel the old fashion way: they forge it with fire and hammers and anvils. But this is not about some homey effort to "keep the old ways alive," This is about professional handcrafting steeped in tradition. After all, Martin Rose founded the business in 1904 and his grandson, Bob Rose, currently helms it.

Billed as an "art blacksmith shop," at Rose, steel meets creation in the most organic sense. Customers can commission custom items such as chandeliers or fencing and the blacksmiths bring the vision to fruition. The shop also hand forges industrial tools such as tongs.

Located in the St. Clair Superior neighborhood, the shop is a museum of sorts as well, with medieval metalwork and classic wrought iron pieces on display, as well as examples of glass carved via reverse-image sandblasting. Four objects from this collection; including a railing from the Drury Theatre, an art deco lamp made by Paul Kiss and a council table and mirror; will be traveling along with "Muse with Violin" to New York for the upcoming Cooper Hewitt show. "The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s" will also be on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art from Sept. 30, 2017, through Jan. 14, 2018.

The William G. Mather, North Coast Harbor

Clevelanders consistently wax romantic whenever a freighter glides before them, whether it's up close while they quaff an ale on the patio at Merwin's Wharf or from afar as they rock to and fro on the bench swings at Lakewood Park.

One of the grandest dames of the Great Lakes to garner sighs and wistful grins is the William G. Mather. She was built in 1925 by the same company that constructed hundreds of vessels, including the doomed SS Edmund Fitzgerald – the Great Lakes Engineering Works in River Rouge, MI. At just over 618 feet long and with a 14,000-ton capacity, the Mather was the flagship of the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Company until 1952. Retired in the early 1980's, she is now, of course, a floating museum and part of the Great Lakes Science Center.

Visitors can explore her gracious guest quarters, engine room and wheelhouse amid other exhibits, which is surely worth the $9 admission and then some.

As visitors walk the decks of the Mather, however, they are not likely to encounter a car. That wasn't always the case. For a time, she and her ilk not only transported the ore destined to become steel, they also carried the new automobiles made from that steel – on their decks. Call that a way to leverage an asset.

Lastly, there is no better place to conclude this roundup than from inside the William G. Mather. Here, museum-goers can literally peer into what held the very essence of the Rust Belt – the freighter's cavernous cargo hold wherein raw iron ore was transported to ports across the Great Lakes and unloaded courtesy of the storied Huletts for more than five decades.

For those wanting to round out the nautical tour experience, Mather visitors can hop over to the 1942 U.S.S. Cod for an equally affordable $12 tour. Both of these iconic ships reopen to the public in May.