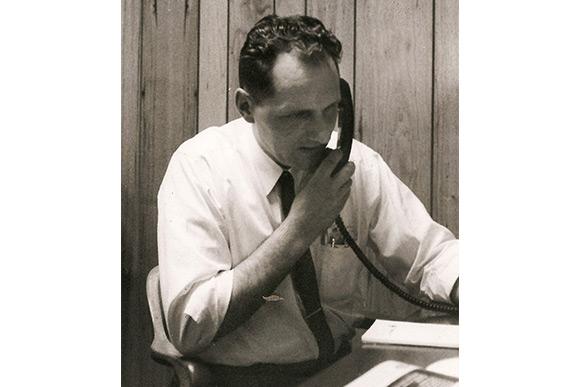

Q & A: Frank Samsel

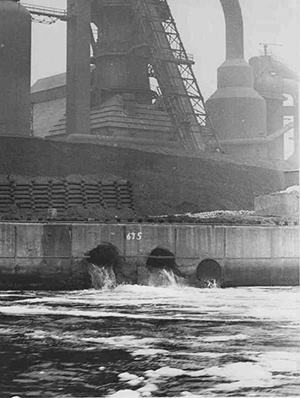

It’s hard to imagine any good resulting from the infamous June 22, 1969 Cuyahoga River fire, but the incident sparked the mid-1970’s environmental movement and inspired creation of new technologies to clean water and air. The fire was also one impetus for the federal Clean Water Act.

Frank Samsel, a lifelong Greater Cleveland resident, was an innovator and unsung hero in the river cleanup. He designed a boat, the Putzfrau (German for “cleaning lady”) that removed solid waste, oil and petroleum products from the river. Earlier in life, he had sailed the Cuyahoga and Lake Erie on bulk carriers, and received training as a welder. After a stint in the military during the Korean War, he sold wire rope, tackle blocks and rope fittings for the Upson-Walton Co. In 1958, he branched out on his own and established Samsel Supply, which carries construction, industrial and maritime supplies.

Today, the 87-year-old lives in Avon. His five children still run Samsel Supply on Old River Road in the Flats.

Fresh Water contributor Bob Sandrick caught up with Samsel to chat about his experiences sailing the lake and cleaning the Cuyahoga.

How did you first start sailing?

When I was about 16 and living in Olmsted Township, I had a neighbor across the street — a second mate with Hutchinson and Buckeye Steamship. Hutch and Buckeye had a fleet of about 35 boats. The neighbor asked me if I wanted to work on the winter crew. It was a chance to cut school occasionally, so I said yes. I did whatever I was told to do. After high school, I became a full-time deckhand. The Korean War was going on, so I’d figure I’d sail the lake until I was drafted. I did that for part of two seasons, loading and unloading, painting, chipping and scrubbing.

What did you think of the work at the time?

It was hard work but you’re a young fella growing up and you’re going to different places and seeing different things. It was a life experience. You’re living in close quarters with other people and learning to live together and eating good food.

What was the Cuyahoga River like at the time?

It was an open sewer.

The Cleveland sewage department did some primary wastewater treatment, but they would send what they couldn’t service into the river. There had been a law passed at the turn of the century that said no pollutants could go into the river, but business was so powerful then, they had the law changed, so they could throw their waste products in.

What else was in the river?

What else was in the river?

You would see stuff in the river that you could identify, and some you wouldn’t want to identify. You would find everything from park benches to screen doors. There were countless balls that had run down into the sewers, from kids playing in the streets, and they would end up in the river. Hundreds and hundreds of balls. If it floated, it was in the river.

There was a lot of dead lumber in the river. We found cattle hides and entrails that butchers had thrown in. It was so polluted that when the water got warmer in the summer, it produced methane from the bacteria. The river was bubbling, like a pot of water just starting to boil. When we were there, nobody wanted to be down by the river in August. The stench would drive you away.

How did flammable liquids get in?

Oil that was used for fuel on the ore boats was about three cents a gallon. If you had oil left over in your fueling line, it was cheaper and more expedient to dump it into the river. You’re not losing a dollar and you would save a ton of labor because you wouldn’t have to go to the expense of avoiding a spill.

Also, much of the machinery in factories along the river used oil for lubrication. The oil would drip off the bushings; flow down the sewers and into the river. That was an acceptable way of doing things, going back to before the 1940s. During World War II, they had really big fires on the river. Sohio spilled gasoline into the river because they didn’t have overflow controls for their storage tanks.

So the 1969 fire wasn’t the first. What sparked these fires?

In my time, rail cars carrying molten metal would cross bridges over the river. Hot slag would spill from the cars and onto oil-soaked debris trapped in the river on bridge abutments.

You were running a successful business, Samsel Supply, when the Cuyahoga cleanup started. How did you get involved?

We had a workboat and we would deliver orders to ships in the river, so we were up and down the river every day. We knew the river like you knew your way to work, and we knew what was in it.

In the early 1970’s, after the river fire, they created the Environmental Protection Agency and passed the Clean Water Act. All the companies on the river, like Republic Steel and the old J & L (Jones and Laughlin Steel Corp.) got together to comply with the new law. They formed the Cuyahoga Remedial Action Committee to solve the problem.

I came up with an idea that we patented — an integrated system of boats cleaning the river and trucks hauling away debris. We went to the committee meetings, and they said they would hire us if we were successful and competitive. We formed a new company, Samsel Services, and we built the equipment, and it was as efficient as any equipment ever constructed. I haven’t seen anything that can match it as far as production goes.

Tell me about the Putzfrau. How did it work?

We had three principals. First, we had an articulated clam – like a modified log handler, but smaller – on the back. It had a steel mesh liner and picked up very small debris, trees and trash. On the front, we had a modified Vactor system, which today cities use to clean catch basins, but it was a new technology back then. It vacuumed liquids and anything as large as a volleyball into a holding tank. Then, we had a trash pump that would transfer the liquid and small debris into a tank on shore for disposal.

We had a five-seven-man crew with the ability to pick up about 1,500 gallons in an hour and about 16 cubic yards of debris. We had a modified truck so we could unload both liquids and solids. In 12 hours — in ideal conditions — we could pick up about 100 cubic yards of debris and 15,000 gallons of oil. We could handle most spills in one day. And when we started on a spill, we worked until we were finished.

Where did you take all this debris and polluted water?

In the beginning, we would take solid debris to a big landfill Republic Steel had off Independence Road. Yucca Flat, we called it. And at Research Oil (Co.) on Independence, we could dump oil and water. They would let the liquid settle, reclaim the oil and send the water back into the sewer.

That was the beginning of recycling.

Who paid you for all this work?

We worked with a lot of different companies – steel companies, chemical companies and tank farms. If the (U. S.) Coast Guard was able to identify the spiller, the spiller paid us. If the coast guard didn’t find the spiller, the coast guard paid.

We had standing contracts with Republic Steel and other companies and cleaned up spills that would come out of their plants, due to their lubricating systems. As the river cleaned up, companies started cleaning up gas stations. When they converted from steel to fiberglass tanks, we did a lot of underground cleanup, but we had to get different equipment for that.

Were you the only ones cleaning the river?

No, we had competition. The Coast Guard would call us out there along with other people. But the others didn’t have the equipment or expertise. And their costs were much higher. We were very competitive and handled some very large spills.

How long were you involved in the cleanup?

About seven years. Companies started to modify their operations or go out of business, because if they had dirty operations, the fines made it unprofitable for them. Then we went into land spills. It got to the point where each type of spill required a different type of equipment, and the laws were coming by the hundreds, like water running over Niagara Falls. Companies couldn’t keep up with it. Eventually we sold the environmental company.

Do you consider yourself an environmentalist?

Yes, I’m an environmentalist, but not a tree hugger or a vegetarian. There is a common-sense way of doing things both on land and on water. And we have to think a lot smarter and we have to use common sense.

So how is the river doing today?

Pretty good. We have fish populations. People are catching steelhead trout up the river. I know fellas that fish in the river, they are catching bullhead, rough fish like catfish and the occasional perch.

It’s made about a 180-degree turn.

The Cuyahoga today

The Cuyahoga today