Navigating the challenges in protecting Cleveland’s homeless from COVID-19

It’s a hot Friday morning at 2100 Lakeside Ave. as director of operations David Blunt walks out into the yard of the homeless shelter for men in Cleveland’s St. Clair Superior neighborhood.

He eyes some residents hanging out at a table, watching television, and talking, when he quickly notices something.

“Hey fellas, put those masks on… put those masks on, gentlemen!” Blunt hollers.

Blunt says there’s plenty of things the shelter, run by the Lutheran Metropolitan Ministry (LMM), has done to keep its residents safe during the COVID-19 pandemic:

Mandatory temperature checks at the door; mandatory mask wearing (residents are given a mask if they don’t have one); removing the top bunks from the beds in the shelter’s congregant-living area; and reducing the shelter’s capacity of roughly 400 beds by half.

Some at-risk shelter residents have been placed into area hotels.

But there’s one key piece that was missing back in March at the beginning of the pandemic: Access to COVID-19 testing to make sure that the virus doesn’t endanger the lives of the homeless staying in shelters.

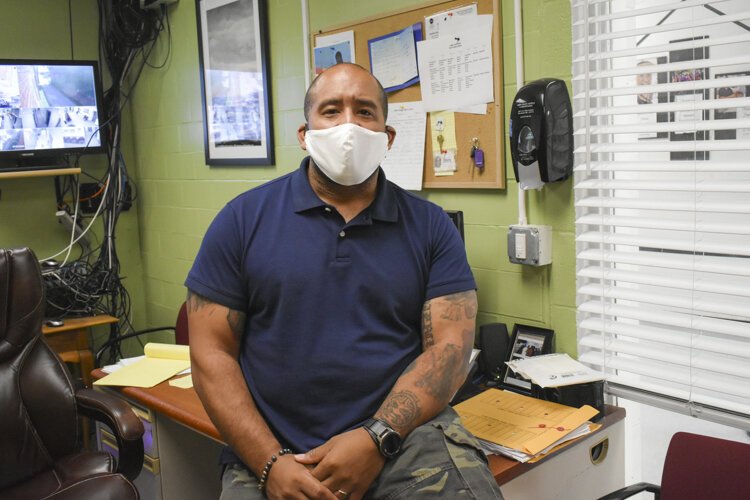

David Blunt, shows how the shelter has set-up a plexiglass barrier at its entryway to protect residents and staff during the pandemic.Recognizing that major gap in early May, workers with the MetroHealth System partnered with the Cuyahoga County Board of Health to test almost 1,100 people living and working in Cleveland-area shelters for COVID-19.

David Blunt, shows how the shelter has set-up a plexiglass barrier at its entryway to protect residents and staff during the pandemic.Recognizing that major gap in early May, workers with the MetroHealth System partnered with the Cuyahoga County Board of Health to test almost 1,100 people living and working in Cleveland-area shelters for COVID-19.

As of late July, officials found that 33 people tested positive for COVID-19, or about 3%, according to MetroHealth spokesperson Dorsena Drakeford.

Compare these findings to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study of homeless shelters in Boston, for example, where roughly 36% of shelter residents and 30% of staff tested positive for COVID-19 in early April.

Ramping up testing

The low number of positive cases at the local shelters speaks partly to efforts to de-populate those shelters, according to Michael Seidman, an assistant professor of family medicine at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and family medicine physician with MetroHealth.

Recently, the number of hotels used to reduce overcrowding at the shelters and practice social distancing has increased from two to four, according to a statement from the Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless (NEOCH).

Seidman led MetroHealth and Cuyahoga County teams in providing mass-testing to staff and residents at the various shelters around Cleveland, as well as in some homeless camps.

Seidman says the effort is crucial because these are people who don’t have health insurance or easy access to healthcare, and don’t necessarily have the most up-to-date information on the coronavirus.

“One of the main things that we’ve done when our team has gone out to either screen or test is to be able to, face-to-face, answer some questions to the best of our ability, both shelter staff and clients,” says Seidman. “You know a lot of those folks don’t have phones, so the information [they] get is sporadic and maybe contradictory.”

Michael Sering, vice president of housing and shelter with LMM, says their partnership with MetroHealth is important for the safety of the shelter residents.

“They were able to test everybody at the shelter, so we were able to do one big mass testing just to get started,” Sering says. “And now they come a couple times a week and they test any of the people who are new to the shelter.”

Sering says they continue to take precautions with a constant influx of new residents. “Within the shelter itself we have separate areas—so when we have new people, they would be designated to one area until they’ve been tested,” he explains.

Beau Hill, executive director of the Salvation Army of Greater Cleveland’s Harbor Light Complex, said their two shelters—one for men and one for families—had a significant portion of their residents and staff tested for COVID-19 through the same MetroHealth/County effort.

While the Salvation Army’s shelter staff do help residents get tested for COVID-19, and strongly recommend their residents wear masks, Hill says they aren’t requiring new residents to be tested or to wear a mask.

“If we make it a hard and fast rule that you’d have to wear [a mask], we’d eventually have to kick people out,” Hill explains. “Do you want to kick homeless people out of a shelter because they’re not wearing a mask? That doesn’t make any sense.”

LMM’s Sering says 2100 Lakeside staff have successfully gotten residents to comply with its mandates, and says the shelter has a system of sanctions if residents don’t comply—stopping short of kicking people out.

Lutheran Metropolitan Ministry’s men’s shelter at 2100 Lakeside Avenue in Cleveland.A set of guidelines

Lutheran Metropolitan Ministry’s men’s shelter at 2100 Lakeside Avenue in Cleveland.A set of guidelines

Bobby Watts, CEO of the nonprofit National Health Care for the Homeless Council, says there are several constants that all congregant-living shelters should be doing during the pandemic.

The big three are requiring residents to wear masks; spacing out residents; and constant cleaning.

“The term that’s come into use is to ‘decompress’ areas,” Watts explains. “Decompress the cafeteria, the same with classrooms—basically, limit the amount of people that can be in there at one time.”

Watts adds that those shelters with chapels may broadcast services to various parts of the building, instead of hosting everyone in the chapel at the same time.

Watts says it’s good that some shelters are providing regular COVID-19 testing for their residents but the lag time for getting results back—and the variability of supply and access to testing—means that shelters should not be requiring a negative COVID-19 test before admitting people (neither 2100 Lakeside nor the Salvation Army do this).

Challenging times

Hill and Sering both say the pandemic has presented a host of difficulties for their shelters, even as the need for their services has increased.

Hill says the Salvation Army has depopulated its shelters to increase social distancing—from about 475 across all their area residential programs down to about 400.

But the move comes with a big negative: less government funding, which matches the number of residents being served.

Less revenue means less ability to serve an already-vulnerable population of people during the pandemic, Hill says. However, he says the layout of the residential areas in the family shelter does naturally lend to social distancing, with families in separate living units.

Between the beginning of the pandemic and early July, the Salvation Army had 15 out of 145 staff and roughly 25 of about 215 residents test positive for the coronavirus.

LMM’s Sering declined to say how many residents and staff tested positive, but he says his shelter’s ratio of positive cases has been close to the 3% country-wide number found in MetroHealth’s shelter survey (the nationwide daily positive case rate was around 6.75 percent at the end of July).

Christopher Knestrick, executive director of NEOCH, says the pandemic has closed many places where many homeless people go to charge a phone or get free Wi-Fi, and therefore there is a lack of knowledge or spread of misinformation among the homeless community.

To combat that, NEOCH’s Outreach Collaborative has tried to engage with “as many people on the streets as possible,” including checking in with people through its East Side and West Side Homeless Congress groups, Knestrick says. Outreach workers also accompany homeless clients to medical centers like Care Alliance to get tested for COVID-19.

“We are regularly making calls and checking in with people who are staying in shelters or on the streets to communicate important updates,” says Knestrick. “Word-on-the-street has always been the most powerful way to spread news and updates to those unhoused in our community, and that can be a real challenge when we want to communicate important information with people who are already vulnerable and struggling to meet basic needs.”

David Blunt inside the shelter’s dormitory room, where the shelter has attempted to space out beds as much as it can.Back at 2100 Lakeside, Blunt says they have trouble keeping residents distanced—even with the reduction of people in the shelter.

David Blunt inside the shelter’s dormitory room, where the shelter has attempted to space out beds as much as it can.Back at 2100 Lakeside, Blunt says they have trouble keeping residents distanced—even with the reduction of people in the shelter.

A recent study by the Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA), which has long had a partnership with LMM, found that to achieve adequate distance, the shelter would need to have a maximum of 120 residents. It’s currently hovering at around 180, Sering says.

The shelter is having residents sleep head-to-foot, which is one recommendation, but there’s not enough room to space the bunks out adequately.

It's possible to get the shelter down to that level recommended by the CIA, Sering says, but only if there isn’t a surge of additional people needing shelter.

Some experts are predicting a wave of evictions to crash across the country with eviction-moratoriums now expired and much of the support from the federal government running out. If that happens, 2100 Lakeside may need to bring back its top bunks, Sering says.

But still, there’s hope for a more long-term solution.

“We have continued to work with the county on more people going to hotels,” Sering says. “We also have an initiative with the city as a COVID response—for some of our hard-to-place people, we’re going to be looking at renting apartments that we would manage—we’ve projected [we will] get 75 people out [of 2100 Lakeside] over the next 12 months.”

Conor Morris is a corps member with Report for America. You can find him on Twitter at @condormorris, or email him at cmorris@advance-ohio.com. This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 16-plus Greater Cleveland news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland.