Building on hope: I_You Design Lab aims to give the displaced a sense of home

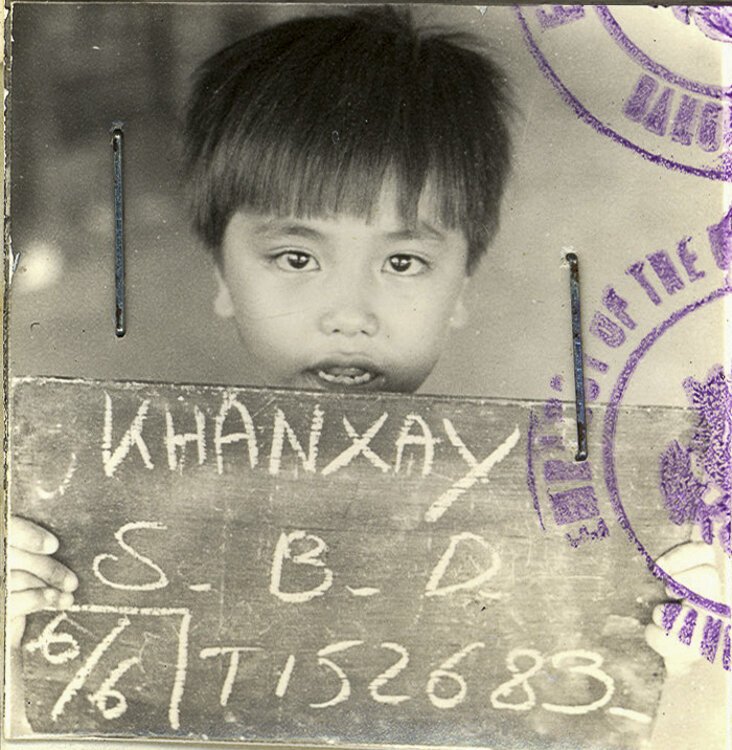

Sai Sinbondit knows the strains of being displaced from his home. As a boy, he lived in Laos with his parents and three older sisters. His mom is Vietnamese, and his dad is Thai; Sinbondit was born in Laos where his dad was teaching.

Then war broke out, forcing the Sinbondit family to live for several years in a refugee camp on the Laos-Thailand border. The family arrived in a small northwest Ohio community in April 1981 when Sinbondit was six years old.

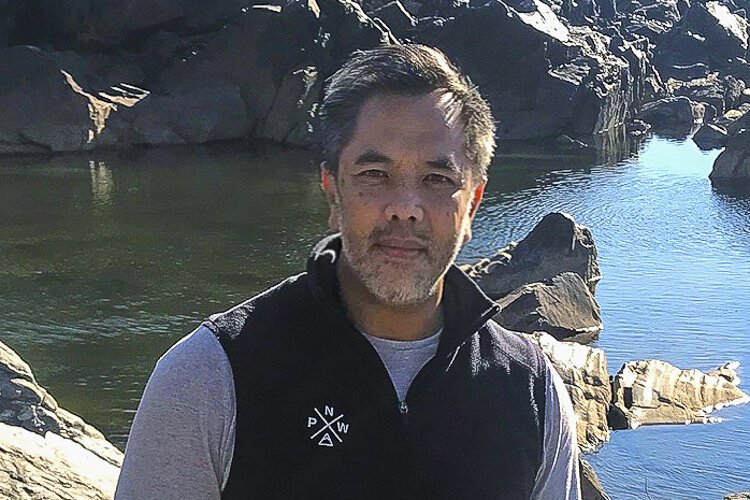

The experience of living in a refugee camp led Sai Sinbondit to create I_You Design LabAlthough his memories are vague, Sinbondit says the feelings of being displaced from his home and his life are something he lives with every day. But the experience of living in a refugee camp eventually led him to create I_You Design Lab in June this year—a company dedicated to designing and building shelters for displaced populations. Sinbondit’s vision is to improve the quality of daily life for the vulnerable through design and development of shelters and products.

The experience of living in a refugee camp led Sai Sinbondit to create I_You Design LabAlthough his memories are vague, Sinbondit says the feelings of being displaced from his home and his life are something he lives with every day. But the experience of living in a refugee camp eventually led him to create I_You Design Lab in June this year—a company dedicated to designing and building shelters for displaced populations. Sinbondit’s vision is to improve the quality of daily life for the vulnerable through design and development of shelters and products.

“[The word] ‘displacement,’ nowadays, people hear all the time, but I don't know if people really know what that means,” Sinbondit explains. “From people being displaced down in Florida by a hurricane, to all the refugee problems that we're having across the world—from Ukraine to Africa, to Myanmar to Southeast Asia, and even at the southern [U.S.] border. Refugees and immigrants—populations that are displaced within their own community. That includes the United States—such as the homeless population.”

Sinbondit started I_You Design Lab, a nonprofit design and architectural collective meant to create a sense of place, as well as a sense of security, in these temporary homesteads. “We help lift the quality of daily life for people who are vulnerable through design and development of shelters and products,” he explains.

The team leverages research, design, and mindful construction of the built environments as tools to address fundamental needs, dignity, the local community’s health, and environmental stewardship to elevate the quality of life to displaced and underserved communities.

“Our focus is providing the design tools and architectural tools for either the organizations that supports [displaced populations] on the front line or working directly with these populations to create a better quality of life for themselves or at least help lift them up,” Sinbondit explains. “I'm talking about design and architecture. It doesn't mean color selections or buildings’ shapes and forms. It really looks at like the research and critical thinking from the design point of view of planning, like sustainability material efficiencies.”

Sinbondit works with North Ridgeville-based 30 Hearts and Ethiopian nonprofit SVO in developing design concept and construction plans for a Family Center First Aid Clinic & Community Support CenterBuilding on experience

Sinbondit works with North Ridgeville-based 30 Hearts and Ethiopian nonprofit SVO in developing design concept and construction plans for a Family Center First Aid Clinic & Community Support CenterBuilding on experience

Sinbondit says his motivation comes from his experiences living in the Laotian refugee camp as a child.

“I get snippets of our past here and there from my three older sisters and parents—they don’t like talking about that part of our past very much,” he explains. “Throughout my life, I’ve been trying to piece the parts together. Oddly so, working with displaced populations somehow helps me to understand part of myself that is sometime vague to me.”

Sinbondit says the idea of creating spaces, shelters, living areas, and even communities, for displaced populations has been an idea that has been brewing for almost his entire life.

“So, it started very young. I mean just trying to figure out how to communicate and help people through art and design,” he says. “So, I think it just slowly marinated. And then at some point it just kind of was nagging me so much that couldn't ignore anymore. And that was last October.”

While Sinbondit has been working on his business concept for several years, the site officially launched this week. I_You Design operates out of Cleveland and Washington, D.C., and Sinbondit says he is opening offices in Charlotte, North Carolina and Barcelona, Spain in early 2023.

Sinbondit arrived in Cleveland after earning his graduate degree in architecture at Syracuse University in 2007 and he has worked as a designer for top local architecture firms like Bostwick Design Partnership and Bialosky. He and his wife, Amy Krusinski Sinbondit, who is from Northeast Ohio and has family in Slavic Village, moved to D.C. in 2016 for his wife's career in ceramic arts, but they still have close ties to the area.

Additionally, he’s been working with organizations like Lutheran Metropolitan Ministry (LMM) and Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA) to create social change through his concepts and designs.

For instance, at CIA, Sinbondit taught social engagement courses and worked with students to leverage art in making positive social community changes and awareness. He worked in 2016 with students on projectFIND: People + Shelter + Food + Mapping, in which they researched, designed, and developed pocket-sized resource maps for 5,700 individuals and families experiencing homelessness in Cleveland.

In fact, two of the CIA graduates who worked on projectFIND in 2016 are now part of the I_You Design Lab research and development team.

“Through this research and development arm of I_You, we are advancing the design and implementation for various displaced communities, such as Ukrainian refugees, hurricane victims, people out west who have been affected by fire, and assisting overflow spaces for our homeless community during winter months (such as in church basement or in gymnasium),” says Sinbondit.

Attending to Cleveland’s homeless

Attending to Cleveland’s homeless

Since 2018 Sinbondit has served as project manager for LMM’s Breaking New Ground $3.5 million campaign launched in 2019 to buy and renovate 20 homes by 2024 in the St. Clair-Superior neighborhood.

Sinbondit was one of the pioneers on the Breaking New Ground project, and in August, LMM celebrate the completion of its first house—Bonna House—as well as exceeded its $3.5 million fundraising goal by more than $1.2 million, having raised $4,245,000, and acquired seven additional houses in the neighborhood.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, Sinbondit worked with Michael Sering, LMM vice president of housing and shelter, to create individual shelters within the Men’s Shelter at 2100 Lakeside’s sleeping area to mitigate the spread of the virus. He says the plywood designs, with cutout areas was a simple, utilitarian, cost effective way of effectively slowing the spread.

“[The system is] efficient, durable, and definitely affordable—and we don't need a special skilled trades person to put this up,” he says. “The idea is that this pod is almost like IKEA furniture where you have a minimal direction, and we can utilize multiple workforces at different skill levels to put these up quickly.”

Sinbondit adds that the cutouts in the shelters were not for aesthetics. “These patterns were more for utilitarian purposes for instances of visual checks,” he explains. “When the staff walks around at night, they don't need to open the door and check [on people]. They can just peek in to make sure the individuals are okay in there. And at the same time, it also helps with the air circulation.”

The men staying at 2100 Lakeside gave positive feedback about the individual shelters to Sinbondit and his team. “It gave them a sense of privacy,” he says. “So better privacy also meant a sense of security—because with the space around them they feel more secure rather than being out in the open.”

Sinbondit maintains a design focus on being ecofriendly and sustainable. “Around 60% of our carbon footprint is produced in the construction industries with all the material waste,” he explains. “So, we’re looking at how we can efficiently build and make it affordable for populations.”

Going worldwide

Additionally, Sinbondit says the men had sense of security and privacy. He says he’s working with CIA students are creating similar structures for Ukrainian refugees and natural disaster victims who are staying in mass shelters and camps.

On an international level, Sinbondit works with North Ridgeville-based 30 Hearts and Ethiopian nonprofit SVO in developing design concept and construction plans for a community in Bako, Ethiopia that includes family and community center, six homes, a first aid clinic, library, community kitchen, learning center, and case worker offices.

On an international level, Sinbondit works with North Ridgeville-based 30 Hearts and Ethiopian nonprofit SVO in developing design concept and construction plans for a community in Bako, Ethiopia that includes family and community center, six homes, a first aid clinic, library, community kitchen, learning center, and case worker offices.

“My role with [30 Hearts] is to design housing for the orphaned children and the women that that dedicate their life to take care of them,” he says.

He and his team are currently working on creating shelters in Ukraine, working on a belief that refugee camps and shelters need to stop being considered “temporary” housing.

“All refugee camps are described as temporary,” he says. “But I think 99%—if not 100%—of refugee camps are always permanent.”

That belief stems from his childhood days living in the Laos-Thailand border camp. The concept started developing when Sinbondit was in graduate school.

“Instead of designing skyscrapers and towers, I was looking at refugee camps and how to plan refugee camps mindfully,” he says. “We want to provide design and architecture as a tool—make it accessible for populations that normally can't afford design and architecture, so they don't become shantytowns or slums. We can mindfully plan refugee camps. There are refugee camp examples throughout the world that have really poor living conditions because it wasn't planned ahead.”

.jpg)