Conquering barriers: One refugee’s story of fulfilling his career goals in Cleveland

Juvens Niyonzima grins with excitement as he enters the ice rink at the Cleveland Heights Community Center for the first time.

“It has always been my dream to ice skate” says Juvens, who was born in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). “But we didn’t have ice where I grew up in Africa. So, I just did a lot of rollerblading.”

Juvens NiyonzimaIt doesn’t take long for Niyonzima to master the ice. Within minutes, he is twirling, gliding, and skating backwards. When asked by fellow skaters where he learned his moves, Niyonzima shrugs.

Juvens NiyonzimaIt doesn’t take long for Niyonzima to master the ice. Within minutes, he is twirling, gliding, and skating backwards. When asked by fellow skaters where he learned his moves, Niyonzima shrugs.

“It’s the same thing as rollerblading,” he says. “Just on a different surface.”

Yet rollerblading isn’t the only skill that Niyonzima is adapting to fit a new context. Since moving to Cleveland from Rwanda in 2020, Niyonzima has been working to translate his education and job experiences from back home into a sustainable and meaningful career in America.

That process, however, hasn’t been as smooth as his moves on the ice.

The journey to Cleveland

As a child growing up in the DRC, Niyonzima dreamed of either working in science at a laboratory or owning his own media company—offering printing, videography, photography, and graphic design services. Yet his dreams were often interrupted by the country’s ongoing civil war.

“I went to a total of seven schools from primary school to high school,” he recalls. “I had to move all the time because of the civil war.”

Niyonzima eventually received his high school diploma in biology and chemistry from a school in Rwanda. With additional training, he received a certificate in graphic design, and began working in a media production company in Uganda.

Niyonzima then moved to Cleveland in January 2020 as part of the U.S. Resettlement Program. And while he had hoped to either work in a hospital laboratory or for a media production company, he discovered he wasn’t qualified for those positions.

“Everyone wanted me to show my U.S. work experience and high school diploma,” he says.

However, Niyonzima couldn’t afford to return to school full-time. He needed to find a job within three months, before his resettlement agency stopped paying his rent.

“The only job that was available at the time was to be a cleaner at University Hospitals,” says Niyonzima. “So, I took the cleaning job. I worked in that for eight months.”

At the same time, he looked for ways to upgrade his skills.

Barriers to working in healthcare

Niyonzima’s story isn’t unique. While studies have found that half of all refugees in the United States find work within the first eight months of their arrival, their jobs are often not aligned with their skills or education levels. This is true not only for high school graduates like Niyonzima, (who took the cleaning job that didn’t even require a high school diploma), but for those with advanced degrees as well.

The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimates there are over 250,000 immigrants in the United States who have healthcare undergraduate degrees, but are working below their skill levels. This phenomenon, known as “brain waste,” is often due to the lack of recognition of academic and professional credentials earned abroad. For many refugees, diplomas and paperwork are also often lost due to war and frequent migration.

The refugee resettlement process also makes it difficult for refugees to return to school to upskill or receive higher certifications in their field. Many adult refugees like Niyonzima are enrolled in a federally funded resettlement program called Match Grant. This program helps pay for rent, bills, and other expenses. But it is contingent on refugees looking for and accepting work immediately—even if the work is low paying.

This requirement severely limits refugees’ ability to return to school and look for higher paying, higher skilled jobs.

Brain waste has negative impacts both on refugees and the communities where they are living. Underemployment has been found to have a negative impact on refugee’s mental and physical health, and can result in lower life satisfaction. Brain waste also deprives local economies of much needed skilled labor.

Bridge to success

Niyonzima knew that he’d need to further his education in the United States to move up in his field. He first attended courses at Ohio Media School to get exposure to the U.S. education system, improve his English, and receive a diploma from an American institution.

“I went because I wanted to upgrade my knowledge and documents,” he says. “Even though I had a certificate in graphic design from Africa, no one would hire me in that field.”

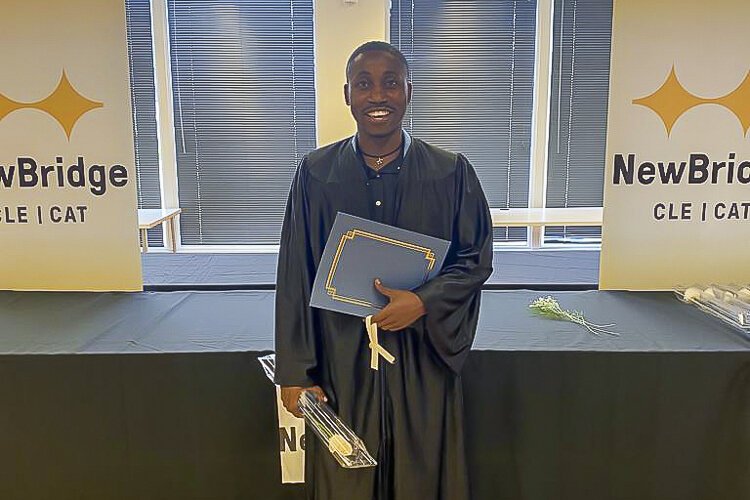

He later attended phlebotomy classes at New Bridge Cleveland. New Bridge helps students to identify and pursue educational and career pathways in the healthcare fields and was uniquelysuited to fit Niyonzima’s situation.

First, the 10-week training program accepted his international high school diploma.

“We’ve had several students from other countries,” says New Bridge director of academic affairs Maya Lyles. “Our goal is to get people employed. So as long as they are eligible to work here, we accept diplomas from other countries.”

It was also free to attend and allowed Niyonzima enough time to continue in his cleaning job.

New Bridge trains approximately 100 students each year in phlebotomy, with a 90% employment rate once students graduate. The course includes a week of soft skills and work readiness, six weeks of in-classroom learning, and four weeks of externships at Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals, or another healthcare facility in the Cleveland area.

Moving up

After graduating from New Bridge, Niyonzima secured a new job at University Hospitals (UH) working as a phlebotomist.

“My managers and coworkers [at UH] got surprised,” says Niyonzima. “From cleaning the trash to working in the laboratory—it’s a big difference.”

Niyonzima says he believes hospitals can help other immigrant employees move up in the healthcare field more easily than he did, however. He recommends offering paid, on-the-job training for refugees with previous experience working in hospitals. That way, they can both earn an income while upgrading their education for an American context and limit the time they spend in low-skills, low-wage roles.

He says he also believes that hospitals need more mentorship for newly arrived refugee employees. Niyonzima has built an informal support group on social media for other Africans who are either working or hoping to work at UH. The group provides encouragement and shares job opportunities, and also raises money for refugee community members in Cleveland who need help.

Finally, he insists that employers should pay more attention to the often-overlooked refugee staff members.

“Many of us, our documents are from Africa, or we don’t have our documents because of the [DRC civil] war,” he says. “That doesn’t mean we don’t have skills.”

This is part three of four-part series exploring barriers to health for Cleveland refugee communities. Read part one here and part two here.

This project is part of Connecting the Dots between Race and Health, a project of Ideastream Public Media that investigates how racism contributes to poor health outcomes in the Cleveland area and uncovers what local institutions are doing to tear down the structural barriers to good health. The project is funded by the Dr. Donald J. Goodman and Ruth Weber Goodman Philanthropic Fund of The Cleveland Foundation.