Standing strong: Cleveland’s gay bars survive the pandemic, catch a second wind

When Ohio Governor Mike DeWine ordered bars and clubs to shut down in March 2020 to stop the spread of the coronavirus, Kevin Briggs panicked. He and his husband John had owned Vibe Bar & Patio, a gay bar on Lorain Avenue near West 117th Street, for only about a year.

Early in the pandemic, they didn’t know how long the shutdown would last or if their fledgling business would survive it.

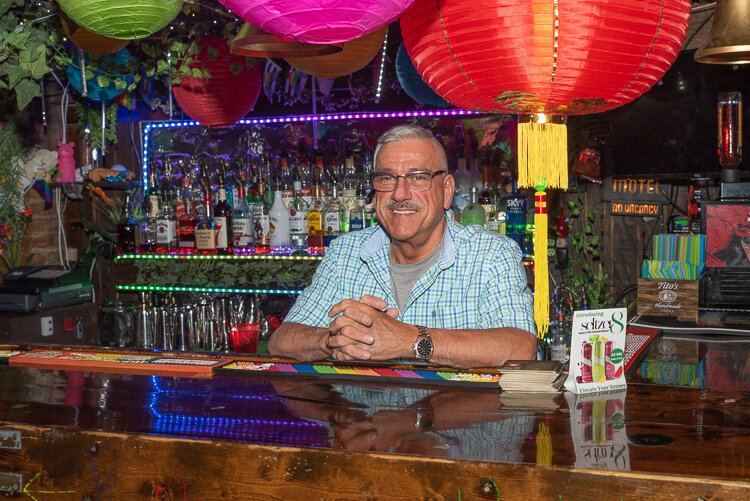

Kevin Briggs and his husband John, owners of Vibe Bar & PatioGay bars and nightclubs in Cleveland and nationally had been closing at high rates for more than a decade before the pandemic, according to research by an Oberlin College professor.

Kevin Briggs and his husband John, owners of Vibe Bar & PatioGay bars and nightclubs in Cleveland and nationally had been closing at high rates for more than a decade before the pandemic, according to research by an Oberlin College professor.

Would the pandemic add to these closures? Not in Cleveland. Vibe, and the handful of Cleveland gay bars and nightclubs in business before the pandemic, remain open.

They’ve often survived by tapping federal COVID relief for small businesses and by coming up with programming that has appealed to patrons’ desires for COVID-safe entertainment.

Briggs remembers the anxiety he felt when he first learned of the shutdown, long before vaccines were available.

“We lose money, that’s one thing, but I was really freaking out about my employees,” Kevin Briggs says. “What are they going to do?”

The Payroll Protection Program eventually helped cover employee wages for Vibe and other gay bars in Cleveland, but business owners had to dig into their own pockets to cover other expenses: internet, utilities, maintenance costs.

“The bills didn’t stop just because we were closed,” says Briggs.

Like other gay bar owners in town, Briggs and his husband had other sources of income to keep the lights on through the three-month shutdown. But the subsequent reopening in May posed further challenges. There were new expenses—masks, sanitizers, signage.

Events that bring customers and additional revenue to town – like CLAW, the national annual leather event downtown—were canceled. Social-distancing requirements limited the number of people who could be served and fear of COVID-19 restrained the number who wanted to be. And while most people obeyed mask mandates and social-distancing rules, others resisted the health orders.

Greggor Mattson, A professor of LGBTQ+ social history at OberlinEven with such events, remaining open before the pandemic was difficult for many such establishments, says Greggor Mattson, a professor of LGBTQ+ social history at Oberlin. His research shows that 37% of gay bars and clubs nationwide closed between 2007 and 2019

Greggor Mattson, A professor of LGBTQ+ social history at OberlinEven with such events, remaining open before the pandemic was difficult for many such establishments, says Greggor Mattson, a professor of LGBTQ+ social history at Oberlin. His research shows that 37% of gay bars and clubs nationwide closed between 2007 and 2019.

That rate has been much higher in Cleveland due to population declines. The number of LGBTQ+ bars and clubs has dwindled from a high-water-mark of over two dozen establishments serving a wide array of community niches in the 1970s and 1980s, to just six gay bars, most small establishments, when the pandemic struck.

Ken Myers, who has owned the Leather Stallion Saloon, near downtown Cleveland since 2014 and officially the city’s oldest operating gay bar, said that keeping a gay bar afloat – even before the pandemic – could be difficult.

“A lot of people don’t understand that many of these businesses are labors of love,” Myers says. “We’re in it for the community, not to make money, we’re just trying to do our best.”

Nearly two years into the pandemic, things have returned to some semblance of normal at Cleveland’s gay bars. Depending on the night, the dance floor at Twist is packed, the pool tables at Cocktails are full, the stage at Vibe is booked, and the (heated) patio at the Leather Stallion Saloon is the place to be. The Hawk boasts a steady roster of regulars and Old Brooklyn's Shade, the newest gay bar in the Cleveland area, is steadily building faithful clientele.

Jim Tasker, manager at Cocktails bar“I think people are going out more now than they used to,” says Jim Tasker, who has managed Cocktails, a bar in the Detroit Shoreway neighborhood, for nearly three decades. “It’s like they were so bottled up for so long from all the restrictions. You could feel that energy at the bar.”

Jim Tasker, manager at Cocktails bar“I think people are going out more now than they used to,” says Jim Tasker, who has managed Cocktails, a bar in the Detroit Shoreway neighborhood, for nearly three decades. “It’s like they were so bottled up for so long from all the restrictions. You could feel that energy at the bar.”

In the year-plus since vaccines and boosters were made widely available and government health orders on businesses were lifted, people have begun doing more of what they used to do. For the gays of Cleveland in particular that often means going out.

“We’re about back to where we were at before the pandemic, attendance-wise,” said Sascha Mascias, a.k.a. Sassy Sascha, a cis-female drag queen who hosts events at Vibe, Twist, and other venues throughout the city. Like many entertainers, she took her routine online to stay connected with her audience during the pandemic but missed the rush of a live audience.

“We’re about back to where we were at before the pandemic, attendance-wise,” said Sascha Mascias, a.k.a. Sassy Sascha, a cis-female drag queen who hosts events at Vibe, Twist, and other venues throughout the city.“The show must always go on!” Mascias says.

“We’re about back to where we were at before the pandemic, attendance-wise,” said Sascha Mascias, a.k.a. Sassy Sascha, a cis-female drag queen who hosts events at Vibe, Twist, and other venues throughout the city.“The show must always go on!” Mascias says.

Nevertheless, COVID is still here, and many people who used to go to gay bars before the pandemic are still staying home, some out of an abundance of caution and others because of lifestyle changes.

Greggor Mattson, whose partner is immunocompromised, is one of those people.

“It’s going to be a while before we’re back at the bars,” he says.

A professor of LGBTQ+ social history at Oberlin, Mattson has interviewed more than 130 LGBTQ+ bar and club owners in 37 states as part of his work researching the decline in the number of these businesses nationwide over the past two decades.

“To some degree it’s a historical accident that bars would be the one place queers could find each other,” he says. “Bars have never been the totality of the LGBTQ+ community, but they’ve been important tent poles. Over time, we’ve acquired more.”

Advances in technology and sociological changes were stressing gay bars even before the pandemic, he said.

With the rise of dating apps and social acceptance of LGBTQ+ people, community members in Cleveland and other cities around the country now have a lot more options when it comes to connecting. Pride flags fly outside of all types of businesses – from board game cafes to coffee shops in addition to other bars. Cruising has become app-based. And, in cities lucky enough to have them, LGBTQ+ centers and other community-oriented spaces provide still more places to meet other than a bar.

Also alcohol consumption habits are changing. Although many people drank more during the pandemic, there are indications that some people—especially Millennials —are cutting back on drinking.

While countless other small businesses in the city have shut down permanently, Cleveland’s gay bars have so-far survived the pandemic.

While countless other small businesses in the city have shut down permanently, Cleveland’s gay bars have so-far survived the pandemic.“That suggests to me that the most vulnerable gay bars had closed before the pandemic,” Mattson notes. “But also, I think the pandemic reminded us that virtual interactions aren’t always a substitute for the in-person pleasure of sitting next to a stranger and getting to know someone who’s perhaps different from you, whether in terms of generation or ethnicity or hometown.”

While countless other small businesses in the city have shut down permanently, Cleveland’s gay bars have so-far survived the pandemic.“That suggests to me that the most vulnerable gay bars had closed before the pandemic,” Mattson notes. “But also, I think the pandemic reminded us that virtual interactions aren’t always a substitute for the in-person pleasure of sitting next to a stranger and getting to know someone who’s perhaps different from you, whether in terms of generation or ethnicity or hometown.”

As the dust of the pandemic settles, Cleveland’s gay bars are adapting to a new landscape. The rise of the Delta and Omicron variants caused further disruptions in business for many places, raising concerns about future waves. And as the pool of customers remains smaller than before the pandemic, some venues are struggling while others thrive.

To lure customers back, most bars redecorated or made other renovations like expanding and weatherizing patio areas, which became popular features in the era of social distancing. Some expanded programming, adding enticements such as drag shows, go-go dancers, karaoke, trivia, open-mic nights and other events. At Vibe, for instance, Briggs launched new events on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays, hoping business would pick up.

“We didn’t do weekday events before, and it’s definitely helping,” Briggs says.

Meanwhile, other bars haven’t changed much at all, relying on a built-in base of regulars.

“We all have our crowds and the different things each bar is known for,” says Myers. He attributes the Leather Stallion’s survival to its roots in the leather and greater fetish community, which the bar will welcome back in full force when CLAW returns in April.

“COVID willing,” Myers says dryly.

Cocktails stopped doing live shows—previously a reliable entertainment staple on Friday and Saturday nights—but people started coming more often for the pool tables and the laid-back, everybody-knows-your-name atmosphere, says Tasker, the manager at Cocktails.

“Whatever we’re doing, it’s working,” he says.

Mattson, the researcher at Oberlin, says the bars most likely to succeed post-COVID will be those that are deeply involved in their community, support other community organizations, and reach out to serve the vast diversity of LGBTQ+ people.

“That’s what the places that have survived here in Cleveland are doing or have moved to do much more,” he says.

Kevin Briggs , Sascha Mascias and John Briggs at Vibe Bar & PatioDespite the historic decline of LGBTQ+ bars and clubs, they remain the most common LGBTQ+ space—particularly in suburbs and rural areas lacking in other friendly spaces.

Kevin Briggs , Sascha Mascias and John Briggs at Vibe Bar & PatioDespite the historic decline of LGBTQ+ bars and clubs, they remain the most common LGBTQ+ space—particularly in suburbs and rural areas lacking in other friendly spaces.

“Those are the places where the decline concerns me most,” Mattson says, “because losing that one place can mean losing the one spot where someone who is newly out or newly widowed can find connection with the community.”

Gay bar owners and managers in Cleveland acknowledge the decline, but says they’re not worried because they understand the need they fill for many parts of the LGBTQ+ community.

“Times have changed,” says Tasker, the manager at Cocktails, “but I think some people will always feel more comfortable going to a gay bar.”

For that reason alone, he thinks there will always be at least one gay bar in Cleveland. But that’s really up to patrons.

“Whether or not Cocktails is still here in 15 years – I hope so; [even though] I won’t be!,” he quips. “But if the customers don’t support and keep supporting their local gay bars, they will become a memory.”

Peter Kusnic is a writer and editor based in Cleveland.

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 18-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland.