Lead in Cleveland: confronting a silent killer

This series of stories, "Grassroots Success: Awakening the Power of Families and Neighborhoods," explores how meaningful impact on our communities grows from the ground up. Support for "Grassroots Success" is provided by Neighborhood Connections and NewBridge Cleveland Center for Arts & Technology.

The Greater University Circle Community Health Initiative (GUCCHI) is funded by a grant from the Cleveland Foundation.

Demetrius Wade was a normal infant when he was born on January 20, 1983. For the first two years of his life he was a typical happy child; however, by the time he turned two, his personality had changed.

“When he was born he was laughing,” his father Darrick Wade explains, “but by the time he was two years old he was real aggressive. He was still in Pampers at his grandmother’s house, and he said something to her. She couldn’t understand him and he took the back of his hand and slapped her glasses and her cigarettes off of the table and shook the chair.

"I started watching him, and it got worse.”

Wade says the next serious episode came when a fifth grader refused to walk to and from school with five-year old Demetrius.

Demetrius Wade“He [Demetrius] fought that boy every day all the way to and from school,” Darrick says of his son. “He was very mean. He was murderously mean.

Demetrius Wade“He [Demetrius] fought that boy every day all the way to and from school,” Darrick says of his son. “He was very mean. He was murderously mean.

“By the age of seven, I knew he was a little bit slower in school and he had the aggression and anger problems. I watched him for about five years and I watched all the children in Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority in our building as well as others,” says Wade of Lakeview Terrace, where he lived at the time.

In the late 1980s, Wade was awarded an economic development grant for public housing and he began a construction rehabilitation business working on the units in the CMHA complex in which he lived.

“I was reading the HUD regulations and I noticed the lead dust. I had Demetrius tested at about nine years old and he came back with high levels of lead. So I had all of the other children tested in Lakeview, and their levels were real high.”

Wade says that they were lucky that their CMHA complex off of W. 28th St. and Detroit Ave. was tenant-managed, enabling them to test the children.

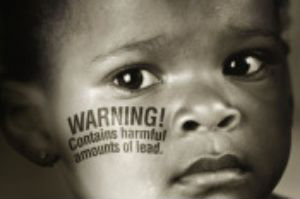

Darrick WadeLead poisoning is linked to brain and nervous system damage resulting in behavioral and learning difficulties, lower IQs, lower academic achievement, antisocial behavior, hyperactivity, emotional issues, and increased criminal and delinquent behavior.

Darrick WadeLead poisoning is linked to brain and nervous system damage resulting in behavioral and learning difficulties, lower IQs, lower academic achievement, antisocial behavior, hyperactivity, emotional issues, and increased criminal and delinquent behavior.

“My son passed September 15, 2007," says Wade. "There was so many things that was wrong with him when he passed that was linked to lead. Because of the damage that was done to his brain, it affected all of the organs in his body… He had an enlarged heart; he had liver problems, kidney problems, breathing problems, diabetes, and problems with his esophagus.”

Living with the illnesses linked to lead poisoning for so many years, the Wade family was used to critical situations involving Demetrius’s health.

“When he died, when I went in there [into his room] and he said, ‘Dad, I’m here’,” Wade recalls. “I got him up and he wasn’t dead, and I was so relieved. I said he’s all right! I made it! So I called 911 real fast and the paramedics came, and they put him on the gurney and he was smiling. I said he’s going to go to the hospital, I know the routine, his stomach’s filled up with bacteria, they pump his stomach, he’ll be in there three to four days and then he’ll come home. I said, 'you want your hat?,' and he said, 'yeah,' and we laughed and I wasn’t worried about a thing.”

About six hours later, the hospital called with the terrible news.

“I just lost it because I thought I got him there in time,” says Wade. “I thought I got him there in time. He was up; he was talking like usual. I thought I got there in time.

“And I think about that a lot, then I think about the other kids. I think about the illnesses. I think about how they came on and what order and sequence they came on. Diabetes first, then asthma, then breathing machines, then their hearts start messing up, and then it’s going to attack the organs. It’s a slow process. It was 15 years for Demetrius to go from being diagnosed to death.”

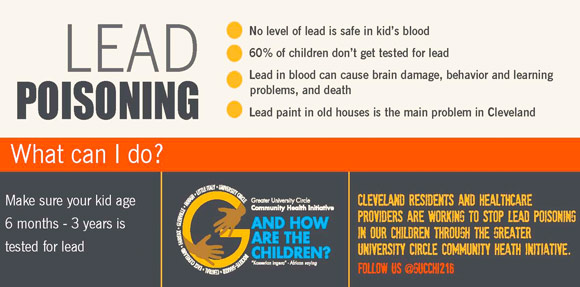

In Ohio, the law requires all children less than six years old be tested for elevated blood-lead levels if they meet any of the following criteria: the child lives in or regularly visits a property built before 1978, the child is on Medicaid or the child lives in an area in which at least 12 percent of the children under six are predicted to have elevated blood-lead levels. State law requires contact from a health department when a child’s blood-lead level is 5 μg/dL or greater. At 10 μg/dL and above, the state requires an on-site public health investigation.

In Ohio, the law requires all children less than six years old be tested for elevated blood-lead levels if they meet any of the following criteria: the child lives in or regularly visits a property built before 1978, the child is on Medicaid or the child lives in an area in which at least 12 percent of the children under six are predicted to have elevated blood-lead levels. State law requires contact from a health department when a child’s blood-lead level is 5 μg/dL or greater. At 10 μg/dL and above, the state requires an on-site public health investigation.

Pre-1978 housing is the largest source of lead exposure and 80 percent of the housing stock in Cuyahoga County falls into that category. The number rises to nearly 90 percent in the City of Cleveland proper.

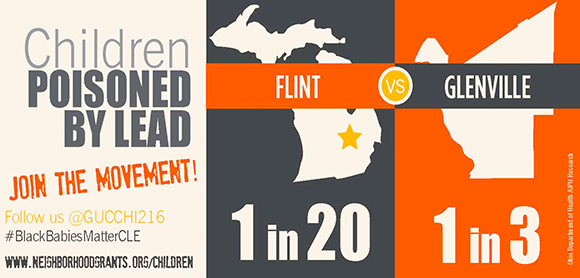

At 10.22 percent, Cuyahoga County had the highest percentage of tested children with elevated blood-lead levels in Ohio in 2014. The individual neighborhoods with the highest levels were Glenville (26.5 percent), St. Clair–Superior (23.4 percent), and Collinwood (20.3 percent). Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) research found nearly 40 percent of Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD) preschoolers had elevated blood-lead levels, the effects of which are irreversible.

There are public efforts underway to address the issue. In 2015, Cleveland received $3.3 million in grants from HUD to investigate 220 homes in which at least three children have been poisoned by lead. Cuyahoga County also received a $2.9 million HUD grant to address lead hazards in 230 homes.

Also in 2015, the BUILD Health Challenge awarded $250,000 to Engaging the Community in New Approaches to Healthy Housing (ECNAHH), a program developed by Environmental Health Watch, MetroHealth, and the Cleveland Department of Public Health to improve asthma, lead-poisoning, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease related to unhealthy housing, as well as prevention-based maintenance and targeted home interventions on the near-west side of Cleveland, including the Stockyards, Clark-Fulton, and Brooklyn Centre neighborhoods.

A problem of this scale, however, is going to require more than public and nonprofit intervention It's going to require the people.

A Grassroots Approach to Lead Abatement

Begun as a qualitative study in spring of 2014, the Greater University Circle Community Health Initiative (GUCCHI) is funded by the Cleveland Foundation and is anchored by Neighborhood Connections (the community arm of the Cleveland Foundation), CWRU, Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals, and local residents. Community partners include the CMSD, faith-based institutions, and local stores, bars, barbershops and salons, among others. The effort stemmed from the Greater University Circle Initiative when India Pierce-Lee, program director for community development for the Cleveland Foundation and Lillian Kuri, the Foundation's program director for arts and urban design, decided to look at the health of the GUC community and reach out to Neighborhood Connections for guidance in building trusting community partnerships.

In 2014, GUCCHI team members interviewed more than 100 people in Greater University Circle community to determine the most critical issues they are facing. Case Western submitted the resulting data to the Cleveland Foundation, which subsequently awarded the initiative $500,000 in April 2015. The group split the funds between Birthing Beautiful Communities, which targets infant mortality rates and an initiative to address alarming child lead poisoning rate in Glenville.

“In Glenville, we took at hard look at the area that had the most children afflicted with lead poisoning and embarked on a survey (which is still underway) to engage, inform, educate residents and ascertain what we can do to assist them (including homeowners) regarding this situation,” GUCCHI project manager Neal Hodges explains. “We hosted a community conversation at the historic Karamu House with acting legend Bill Cobbs and Cleveland Clinic renowned urologist and renal transplant surgeon Dr. Charles Modlin to bring attention to the initiative. We also partnered with CWRU's Milton A. Kramer Law Clinic Center to assist us with policy/systems change.”

In addition to a team of leaders, the group also includes a Health Leadership Committee consisting of senior level executives and residents of GUC and Community Health Action Teams of Glenville residents who meet monthly.

“Every step that we have made, we have collaborated with residents,” Hodges says, “even to the point of choosing what communities to work in. We've held (and still do) knee-to-knee conversations with people. When we meet, we sit in circle, when applicable, or in the round with tables so everyone is equal. Believe me, it hasn't been easy, but what we are dealing with is attempting to shift the cultural thinking on both sides of the spectrum (community and institution alike). We truly are using the upstream approach where we are attempting to address the root cause and we are listening to residents for guidance and answers.”

GUCCHI’s lead action strategy includes building community awareness, remediation, and systems changes. So far members have knocked on nearly 1,100 doors in highly affected area of Glenville to discuss the lead issue, pass out information to residents, and connect them to services. More than 100 residents have expressed interest in having their homes remediated, and GUCCHI is working to get qualified applicants signed up for Housing and Urban Development (HUD) lead remediation grants. They estimate they have reached over 3,500 residents through door knocking, lead awareness parties, and distributing information at community events.

Additionally, members are working to enforce a citywide rental registry of lead-free rental homes; City Council Health Committee Chair Brian Cummins and Ward 9 Councilman Conwell plan to pilot a landlord engagement program to increase registry use. Meanwhile, Kramer Law Clinic is researching policy and advocating for change to increase lead remediation for low-income owners and renters.

Additionally, members are working to enforce a citywide rental registry of lead-free rental homes; City Council Health Committee Chair Brian Cummins and Ward 9 Councilman Conwell plan to pilot a landlord engagement program to increase registry use. Meanwhile, Kramer Law Clinic is researching policy and advocating for change to increase lead remediation for low-income owners and renters.

Per Hodges, when he and his fellow project manager Jackie Matloub started the campaign, they were in unchartered water. They swam through just the same. “What I've learned is that race and racism is a major player/contributing factor with these issues, but people don't want to talk about it. At times it's frustrating, especially when the data tells you the truth – because we deal with data; no personal opinions here. You have to talk about it … It took years to create the monster and it's going to take years to destroy it, but you have to start somewhere.”

Next, GUCCHI hopes to locate non-HUD remediation funds and integrate with GUCI's Greater Circle Living Program to increase affordable housing. The group has also set a second priority of making the area lead-safe within ten years.

“We truly believe in igniting the power of ordinary people to do extraordinary things,” Hodges says. “Residents know their community, and they know their community’s ills. If you listen, they also know how to fix it. They just need some support.”

Battle by Prevention: a Network Forms

In January 2017, the Cleveland Lead Safe Network (CLSN) will convene formally for the first time. Retired Rental Housing Information Network of Ohio community manager Spencer Wells formed the group to secure the passage and implementation of legislation to prevent childhood lead poisoning in Greater Cleveland. The group's goals include ensuring rental units are free of building-related lead hazards, the prioritization of low cost lead hazard control measures, longevity of interim controls, lead-safe repair and properly addressing lead hazards using inspection measures that take into account deteriorated paint and hazardous levels of lead dust. Lastly CLSN is striving for sustainable funding for enforcement and holding landlords accountable for maintaining lead safe housing.

The Network is comprised of individuals and organizations focused on families who plan to work with local government and hold them accountable for public safety. Group members assert that establishing and maintaining lead-safe housing will have the greatest impact on lead poisoning.

“Part of our critique of the [current lead] strategy is that the way in which lead poisoning is usually addressed is that a child has to be poisoned first,” CLSN chairperson Marvin Brown says. “Then after the child has poisoning, the state and other agencies move in to protect the child. Although – as we’ve seen in Cleveland – that actually hasn’t panned out in a way one would hope even though we have legislation on the books. So what we’re looking at doing is a little bit of the opposite approach and trying to make sure that housing is safe for children to move into before they move in rather than discovering that a child has been poisoned then tying to solve the issue after the fact.”

“I was interested because I run the Northeast Ohio Black Health Coalition,” adds CLSN chairperson Yvonka Hall. “We’re the only coalition in the state of Ohio that focuses exclusively on African-American health disparities. When I looked at the lead crisis that we have here in Cuyahoga County, we didn’t have community involvement and engagement. So when Spencer reached out to me, this was an opportunity for my organization to become involved and to help get the community involved.”

The group plans to develop projects with local communities, enlisting residents who are directly affected as active participants. Individuals living or working in Cuyahoga County may join CLSN. Organizations may participate by designating a CLSN member to be a representative and endorsing CLSN position papers.

“We’re just getting started with real membership,” Wells explains. “We have 57 people who have registered to stay in touch, and we’re hoping that a large number of them will convert over to membership over the next couple of weeks. We’ve talked to a lot more people than that … We’ve done some informal outreach to City Council people and got feedback in terms of what they want to do.”

Tasks will include educating local residents about the risks of lead poisoning, steps to improve housing safety and setting up neighborhood workshops for community members to learn about the issues, as well as advocating for the implementation of a Lead Safe Housing Ordinance in Cleveland. Although Wells says the latter is far more important to the group.

“We’re not doing outreach and education primarily,” he says. “We’re primarily doing advocacy to come up with a new way of addressing lead poisoning that doesn’t involve poisoning the children first. We want to get to the houses before the children move in.”

Although meetings haven’t formally begun, group officials have been working hard to get everything in place.

“The reason it has taken a while is to make sure we have something that is comprehensive that actually looks at [the issue] from a different way- from our vantage point and from the vantage point of the community," Hall says. “I think a lot of programs actually start off and don’t really look at how it may be impactful to the community and just throw pieces together. What we don’t want to be is pieces just thrown together, and then we figure out the parts as we go along. We want to make sure that we are as broad as possible in our scope of our services and how they impact the community, and that’s why we’re a network … [CLSN] can encompass all of the ways people are impacted by lead.”

The group strives not only to work toward the goal of a safer environment for residents, but also hopes to fill the gaps in current anti-lead-poisoning actions.

“One of the things we discovered is that nobody in Cleveland was reaching out in any formal way to the survivors of lead poisoning and engaging them through telling their stories,” Wells says… “That outreach directly to community members that are at risk is another one of our goals. We’re not quite sure how that’s going to work. That’s going to take some money to hold a lot of neighborhood workshops, but we’re committed to trying to find that to do it.”

Learn more about how to protect your family from lead exposure here.