Old school still rules: Lee-Harvard’s high census response rate could teach others a few tricks

Miles Hackney has lived in the Lee-Harvard neighborhood for more than 50 years. The brick and vinyl-sided colonial on the city’s east side was new when he bought it in 1968, and so was the neighborhood.

Historically known as Cleveland’s “Black suburb in the city,” Lee-Harvard was a place of opportunity where Black people could afford to buy homes and raise their families in a good neighborhood.

Hackney, 79, and his wife brought up four children here, sharing family meals in the eat-in kitchen, attending block club meetings with their neighbors, and eventually sending their kids off to high school and college. Although the neighborhood has aged – most of his lifelong friends have died or moved, and the basketball hoop that he built for one of his daughters, a star high school athlete, is now rusted, its backboard covered in moss – the area remains mostly stable and the homes are well-kept.

Miles Hackey outside of his home on East 177th Street in the Lee-Harvard neighborhoodWhen asked why he filled out the 2020 census, Hackney had a simple answer. “I’m still living; I gotta be counted,” he said. “Most of the neighborhood is dwindling, so we’ve got to find a way to appropriate the funds.”

Miles Hackey outside of his home on East 177th Street in the Lee-Harvard neighborhoodWhen asked why he filled out the 2020 census, Hackney had a simple answer. “I’m still living; I gotta be counted,” he said. “Most of the neighborhood is dwindling, so we’ve got to find a way to appropriate the funds.”

At a time when the city of Cleveland has a census self-response rate of 50%, the lowest among U.S. cities with a population over 300,000, Lee-Harvard is a rare bright spot. The response rate in the census tract where Hackney lives is 62.3%, and it reaches as high as 70.7% a few blocks to the north in the heart of the neighborhood.

By comparison, the St. Clair Superior neighborhood a few miles to the west, where internet access is at 12% and there is a larger number of hard-to-count groups of people, has a response rate of 27%. West Park, a mostly white, middle-class neighborhood that mirrors Lee Harvard on the west side and has also been called a suburb in the city, ranges from 72.4 to 83.4%.

Stymied by a shortened September 30 deadline and the COVID-19 pandemic, community groups are working furiously to improve Cleveland’s census response rate. An accurate count is important to ensure that the city does not lose millions of dollars in federal resources. Black and low-income residents are especially likely to be undercounted, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Leah Hudnall, Hackney’s granddaughter, says her grandparents grew up in public housing before moving to Lee-Harvard, at a time when housing discrimination kept many Blacks from moving to the suburbs. Hudnall also grew up in Hackney’s house and now lives in the Mill Creek development in Slavic Village. “They [Lee-Harvard residents] have very, very deep roots when it comes to civic engagement, even when you go all the way back,” she says. “That legacy has continued on.”

Hackney is a part of that history of civic engagement. He and his neighbors organized what he called a “vigilante group” to push drug dealers out of the neighborhood when the crack cocaine epidemic hit Cleveland in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. More recently, they organized to push back on a proposed retirement home that could have been sited right across from his house (residents preferred single-family homes).

Lee-Harvard’s strong census participation rate can partially be explained by the fact that there are more homeowners in the neighborhood than in other parts of the east side, according to census data (about 78% of homes are owner-occupied, compared to 40% in other parts of Cleveland), and homeownership might correlate with stronger census response rates.

Lee-Harvard’s median income of $33,491, according to 2010-2014 American Community Survey data from the Center for Community Solutions, is also higher than the city’s average of $26,179; people living below the poverty line are typically another hard-to-count population.

Additionally, Lee Harvard has a relatively high percentage of senior citizens (42.9% receive Social Security income) who grew up in the Civil Rights era and tend to exercise their democratic rights.

Yet residents like Hudnall say the area, which didn’t suffer as much during the 2008-2009 recession as other parts of the east side but also hasn’t rebounded as strongly as other parts of the city, also has a strong tradition of civic engagement. More than anything, this sets it apart from its neighbors and lies at the heart of its success, the residents say.

Elaine Gohlstin, executive director of the Harvard Community Services Center (HCSC), a nonprofit that provides social services and also coordinates development programs within the area, said City Council Ward 1 (which includes Lee-Harvard) in the past had the highest voter turnout of any ward in the entire city; it still has the highest voter turnout on average on the southeast side, she said.

“Some of these residents have been around here 50 to 60 years,” Gohlstin says. “They’re still going out there with their walkers and canes trying to do what they need to do to keep the community together.”

Getting word out

Elsewhere in the city, dozens of community groups have tried every trick in the book to try to boost its ailing census response rate: caravans moving through neighborhoods and big door-to-door census “blitzes,” for example.

Organizers and residents in the Lee-Harvard area, though, appear to have kept things simple.

That’s not to say that a lot of hard work didn’t go into getting the word out, though. Gohlstin says the Lee-Harvard community center held “meetings upon meetings” in the months leading up to the pandemic, reiterating messages about the benefit of completing the census and busting myths about it, including fears that the government would use the information against Black residents.

Once the pandemic hit, public meetings were no longer an option. One of the main contact points became the center’s monthly food distribution, where volunteers could give out information on the census in addition to food.

There is also a “very active” group of retired women, called the Ward 1 Volunteer Navigators, who went door-to-door to make sure folks got counted. “They’re social workers, teachers, people that have always been active and wanted to stay active,” says Gohlstin.

Hudnall suggested the neighborhood’s high census response rate comes partly from the homeowners like her grandfather who have lived in the area for more than 40 years. That means developing relationships with neighbors and stating engaged. So, some communication around the census likely happened organically that way.

“They’re calling one another, holding one another accountable,” says Hudnall. “They’re concerned about the health of their neighbors, and if they’ve been civically engaged or not.”

Kristin Schmidt, manager of the Lee-Harvard branch of the Cleveland Public Library, says her library branch’s patronage is mostly senior citizens who are long-term residents of the neighborhood, “whose stability lends to the higher voter and census turnout.”

Neighborly bonds

Joe Jones, Ward 1 councilperson and lifelong resident of Lee-Harvard, says he wasn’t satisfied with the area’s census response rate and wanted it to be higher. He criticized the federal government for shortening the timeline.

“There should be a fundamental effort to prep at least two years in advance,” says Jones. “Even if my community is getting counted, others are not.”

Both Jones and Hackney say they were concerned about the direction the neighborhood is heading. Many of Hackney’s neighbors have died or moved out, and he says he worries that nearby residents no longer have the desire to be civically engaged. Jones also says he knows new development in the neighborhood has lagged in comparison to other parts of the city—leading to fears about losing vibrancy in the area.

Bill Shelbrick, 42, is a more recent transplant to Lee-Harvard says he thinks the neighborhood’s community spirit is still going strong, noting that during and after he planted his garden in his front yard, many neighbors came by to talk to him.But Bill Shelbrick, 42, a local contractor, lives just a block away from Hackney and had a differing opinion. He said he intentionally moved to the neighborhood nine months ago, citing the friendliness of area residents and the affordable housing. He said he thinks the neighborhood’s community spirit is still going strong, noting there are plenty of young families who live near him.

Bill Shelbrick, 42, is a more recent transplant to Lee-Harvard says he thinks the neighborhood’s community spirit is still going strong, noting that during and after he planted his garden in his front yard, many neighbors came by to talk to him.But Bill Shelbrick, 42, a local contractor, lives just a block away from Hackney and had a differing opinion. He said he intentionally moved to the neighborhood nine months ago, citing the friendliness of area residents and the affordable housing. He said he thinks the neighborhood’s community spirit is still going strong, noting there are plenty of young families who live near him.

“Once I planted my garden, I had people coming from all over the neighborhood stopping by and being like, ‘oh my god, I want to see your garden!’” says Shelbrick.

Jones says she also worries that the COVID-19 pandemic kept many seniors from responding to the census. “It’s lower than what we should have had due to the fact that people are afraid of the virus,” she explains. “It’s probably uncomfortable for people to open their doors and even get counted.”

With little time left, Lee-Harvard’s response rate is still about three points lower than it was in 2010.

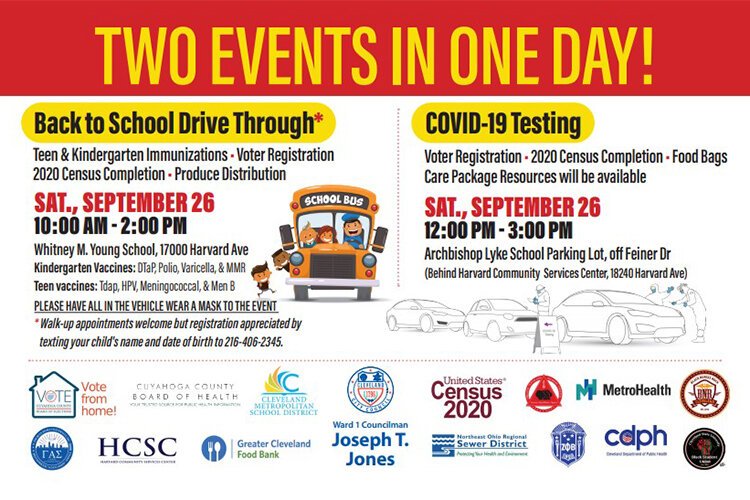

Recognizing that, Jones, the HCSC and other partners are planning a final push on Saturday, Sept. 26 at Whitney Young School and the Harvard Community Services Center—offering free immunizations for kids, mask distribution, voter registration and census outreach.

Even with some work left to do, Lee-Harvard advocates are proud of the work they’ve done.

“We have the largest senior citizen population in the city of Cleveland, yet we’re still getting it done,” says Jones.

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 20-plus Greater Cleveland news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland. You can find NEOSOJO on Twitter and Facebook. Lee Chilcote is founder and editor of The Land, and Conor Morris is a corps member with Report for America.

About the Author: Lee Chilcote Lee Chilcote is founder and editor of The Land. He is the author of the poetry chapbooks The Shape of Home and How to Live in Ruins. His writing has been published by Vanity Fair, Next City, Belt and many literary journals as well as in The Cleveland Neighborhood Guidebook, The Cleveland Anthology and A Race Anthology: Dispatches and Artifacts from a Segregated City. He is a founder and former executive director of Literary Cleveland. He lives in the Detroit Shoreway neighborhood of Cleveland with his family.