Legal clinic helps people expunge criminal pasts

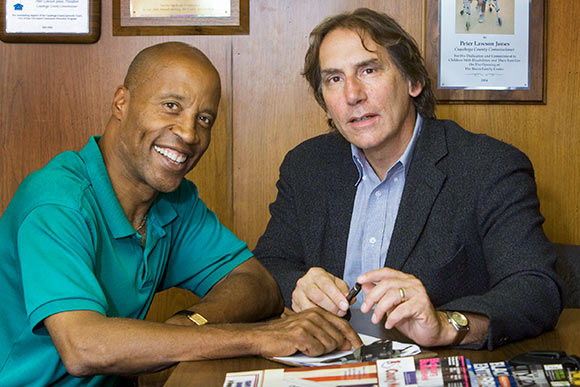

On an overcast Saturday morning, when most attorneys his age are golfing, James Levin sits behind a metal desk in a basement office of the Famicos building on Ansel Road in Glenville, trying to unravel the convoluted legal history of a Cleveland man named Albert.

Just a couple weeks go, Albert held a decent job as a custodian at Progressive Field and before that worked at a McDonald’s on Broadway. Until his employers’ background searches turned up a bench warrant for violating his probation on a domestic violence charge. His boss at Progressive Field told him he could have his job back, if he clears the warrant.

Today, the wiry 44-year-old is anxious, intense, broke and desperate to solve his situation so that he can return to gainful employment. A counselor at the Fairfax workforce center told him about Levin, who runs the Famicos Foundation Legal Works clinic out of the former Notre Dame convent and school that Famicos converted to senior housing.

In chronicling his intricate journey, Albert reveals that since 1989, when he found himself serving ten years in Mansfield Correctional Facility, anger has led to most of his troubles. Most recently, he did another three years for assaulting his now ex-wife.

“It’s always something dealing with my hands, aggression, domestic violence, young man,” he declares to Levin, who’s nearly 20 years his senior. “No dope, nothing else.”

For another 20 minutes, Albert sincerely tries to convey his long and perplexing history of loving and fighting with his high school sweetheart that features fleeing with their son with 12 police vehicles in pursuit, throwing paint on her car, and being arrested in her driveway after she told a police officer that he threatened to kill her and her boyfriend with a bike lock. Levin listens intently, while he peruses Albert’s court docket history on his laptop.

Finally, through a series of pointed questions, Levin cuts through Albert’s Gordian narrative to the present problem: Upon his early release in 2013, a judge put him on probation, and – at his ex-wife’s insistence – ordered him to take classes in anger management and domestic violence, attend Narcotics and Alcoholics Anonymous sessions, and find a job. Couldn’t get to the classes or sessions, he tells Levin, but came close on the job.

“Why couldn’t you get to the classes?” Levin inquires.

“I only had my bike, and we had a bad winter, as you know.”

“I also know that it’s June and has been nice for two months. Take the classes.”

Next, Levin lays out their plan: He will get them on the court docket in a few weeks so they can show the judge that Albert is trying to comply with his probation orders by taking the classes. “Are you clean?” Yes, Albert confirms. Except for the marijuana that he smokes every day, as he has since he was 10. When he waffles about being able to stop, Levin states, “If you want to take care of this and move on with your life, you need to quit now, so that nothing shows up in your test.”

Lastly, he will need to find $20 to pay Levin to go to the Clerk of Courts and $30 to pay for his court appearance. He’s uncertain about the money, but once he returns to his custodian job, Albert promises to repay as much as he can and more. “Just get me tickets if the Indians get into the playoffs,” Levin deadpans.

Last year, Levin approached the Famicos Foundation about opening a legal clinic to help people deal with minor criminal issues that can prevent them from finding jobs, renting apartments, buying a house or a car and so on. The idea was inspired when he was embroiled in a homicide case and was unable to convince key witnesses to testify on behalf of his client because they had warrants for traffic violations, minor felonies or misdemeanors on their records.

“I was struck by how rampant these problems were,” says Levin, who has always balanced his law career defending the poor and disenfranchised with his arts and cultural impresario endeavors, from birthing Cleveland Public Theatre and IngenuityFest to founding the Cleveland World Festival at the Cultural Gardens and the FireFish Arts Festival he’s launching in Lorain this fall.

“They were all problems,” continues the Cleveland Arts Prize winner, “that an experienced lawyer could effectively resolve by going down to the clerk’s office or talking to a bailiff, getting something placed on the docket and getting the warrant vacated or the suspension resolved.”

While citizens can pursue their own expungements, which refers to the ability to seal arrest and conviction records for a clear slate, they usually get lost in the oft-confusing legalities or slip through the cracks of the overloaded court system. Eligible candidates are allowed to have one felony and one misdemeanor. Sometimes, Levin explains, judges will forgive additional minor misdemeanors.

“Expungements aren’t necessarily a high priority for judges, and certainly not for the bailiffs,” he adds. “Early on, I found 8 or 10 of motions that my clients had filed for expungements but were not ruled on that I was able to get placed on a docket and then resolved.”

Famicos approved the project and provided a small monthly stipend to operate the office, and he opened the clinic in April of 2014. Glenville’s Ward 9 Councilman Kevin Conwell also stepped forward, publicizing Legal Works at ward meetings and promoting expungements as a way for people to advance their employment prospects.

Levin holds office hours on Thursdays and Saturdays, and he occasionally does “road shows,” meeting with potential clients who line up at various community locations. Since opening, he has helped more than 200 clients like Albert get their criminal records expunged, resolve sometimes multiple driver’s license suspensions, set up payment plans for fines and court fees, or even write a simple will, like he did for an 83-year-old retired Cleveland school teacher who wanted to leave her home to her caretaker daughter.

One of his clients, Alice Jones, a retired nurse in Cleveland, had a judgment lien placed on her home by a credit card company but had no idea why. After some digging, Levin found the company had the wrong person named on one document and a false signature on another. Still, they wouldn’t vacate the judgment that was keeping Jones from obtaining the bank loan she needed to replace her roof.

Finally, Levin went to the collection lawyers on a Friday and informed them that if they didn’t vacate the judgment by Monday, they were going to see his very elegant, articulate 93-year-old client in front of the TV cameras talking about their credit card and their law firm. Two days later, the judgment was vacated, and Jones got her loan.

“It was scary, and I would have been out of my mind dealing with them if Mr. Levin had not helped me,” Jones says. “He’s an excellent attorney and a nice man who’s honest, patient and works very hard.”

Levin’s decades of experience in law help him with cases in ways a private citizen could never help himself. Like the time he visited a judge he knew in chambers and, after a 40-minute discussion of American history, was able to get him to vacate a couple of his client’s license suspensions.

He also knows that his expungement clients must face “the lottery” of being assigned an empathetic adjudicator. Some judges, Levin relates, are gung-ho to sentence everyone to prison; others work assiduously to keep people out; and the rest are at least willing to consider a good story before issuing a sentence.

“That’s a due process and equal protection argument that’s never really been explored,” Levin says. “There’s a certain randomness to your fate, and if you pull that 10-15% of judges that almost relish putting you away, 18 months of your life could evaporate in jail.”

Currently, Levin is pursuing establishing a second clinic at Pilgrim Church in Tremont. He’s also pursuing additional funding so that he can hire law school graduates and train them to handle routine expungement cases. Before they pass the bar, he can accompany them if they go to court, and it will furnish them with valuable “face-to-face client exposure.”

Because of his commitments to the two festivals in August and September, Levin believes that office will not open before this October. He plans to open another five or ten Legal Works clinics and is in discussion with several councilmen and community foundations throughout the city for support.

Although he’s not sure who else helps people with these issues, possibly the Legal Aid Society of Cleveland, he has enlisted several other attorneys who provide their services pro bono when he needs them. Ultimately, he’d like to see a similar legal clinic in every urban neighborhood.

“The community underestimates the degree that the criminal record and these warrants can drag people back from living their lives or the impact that it has on economic development,” Levin says. “So we should put more legal resources toward this problem.”

As for the growing demand for his legal expertise, Levin concludes with a smile: “I never go to bed at night wishing I had more clients.”

About the Author: Christopher Johnston

Christopher Johnston has published more than 3,000 articles in publications such as American Theatre, Christian Science Monitor, Credit.com, History Magazine, The Plain Dealer, Progressive Architecture, Scientific American and Time.com. He was a stringer for The New York Times for eight years. He served as a contributing editor for Inside Business for more than six years, and he was a contributing editor for Cleveland Enterprise for more than ten years. He teaches playwriting and creative nonfiction workshops at