Business Unusual: Local manufacturers adapt, preserve jobs, and carry on during pandemic

As a high school senior at Max Hayes High School, Nadia Akhlif was looking forward to a celebratory spring—she’d graduate from high school, find a summer job, and attend Cuyahoga Community College in the fall.

But like most Northeast Ohio students, Akhlif’s spring didn’t go as planned.

In March schools closed early and summer jobs fell through due to coronavirus shutdowns.

However, thanks to a new initiative by the Cleveland manufacturer National Safety Apparel (NSA), Akhlif found an opportunity to do an unexpected summer job—sewing face masks.

“I didn’t have any experience using [an industrial sewing] machine before I started,” recalls Akhlif. Her only experience was sewing handmade clothing for her nieces and nephews alongside her grandmother.

Valerie Mayen, owner of Yellowcake Shop, organizes an order of face masks inside her store in 78th Street Studios.“But my instructor [at NSA] was helpful, so it only took me two to three hours to learn how to use the machine and make my first mask,” she continues.

Valerie Mayen, owner of Yellowcake Shop, organizes an order of face masks inside her store in 78th Street Studios.“But my instructor [at NSA] was helpful, so it only took me two to three hours to learn how to use the machine and make my first mask,” she continues.

Creating face masks was not only a new endeavor for Akhlif, but for NSA as well.

Prior to the pandemic, NSA focused on sewing fire and water-resistant safety gear for industrial workers.

The company also ran a training program at its sewing school across from its main office in Brook Park, where it trains its new employees to sew protective outerwear.

When shortages in personal protective equipment (PPE) became evident during the pandemic, the company decided to add surgical gowns and face masks to the PPE line of products it was already making.

The company now produces between 7,500 and 15,000 masks and 1,000 to 2,000 gowns per day.

NSA joins the ranks of several manufacturers across Cleveland that found an opportunity to not only fill a public health need during the coronavirus pandemic, but also generate a new source of revenue to keeps its workforce employed amidst a shrinking economy.

Pivoting to PPE

In late March, former Ohio Department of Health director Amy Acton warned that “The [PPE] supplies we received, and the state’s reserve, will not meet the immediate or future needs of Ohio’s healthcare providers and first responders.”

In response, manufacturing companies across Cleveland stepped in to offer their services.

For NSA, creating masks and gowns was simply a matter of maximizing the resources that they already had available and expanding into an unused portion of the NSA Sewing School building.

“We were able to start creating face masks almost immediately,” says Morgan Farrow, a talent acquisition and human resources coordinator for NSA. “We already had a sewing school, and we had leftover space that wasn’t being utilized. So, we decided to put more emphasis on the training program to use that space efficiently.”

NSA converted its sewing program into one- to three-day intensive training sessions to instruct new employees on mask making, while also continuing to produce the company’s normal PPE products.

Extra space in the sewing school building also allowed NSA to expand from training three or four people at a time to training 10 to 15 people per shift—while maintaining social distancing throughout the expansion.

NSA wasn’t the only local company to make the mask pivot. Other local companies were also able to use mask production to grow (or retain) their workforces and find alternative sources of revenue.

Yellowcake Shop, which typically focuses on designing luxury women’s fashions, had to cancel its lineup of spring fashion events and temporarily close its retail store in 78th Street Studios because of coronavirus shutdowns.

When owner Valerie Mayen heard about the mask shortage, she decided to use her free time to offer to make 500 masks.

The demand was so high that Mayen was able to make masks for both community agencies and make custom masks for individual customers.

Mayen says the switch allowed her to hire 35 men and women, who picked up supplies from Mayen’s shop then sewed masks from home.

The move allowed her employees to maintain social distancing, stay at home with out-of-school children, and still earn an income.

Since March, Mayen has created about 30,000 masks for RTA, Lutheran Metropolitan Ministry’s homeless shelters, and Dave Supermarkets, as well as online customers.

Cleveland Whisky invested in a few new pieces of technology to improve their distilling process, and within three days, the company was bottling hand sanitizer.A smooth transition

Cleveland Whisky invested in a few new pieces of technology to improve their distilling process, and within three days, the company was bottling hand sanitizer.A smooth transition

“I got a call early on [in March] from a representative from the Cleveland Clinic,” says Cleveland Whiskey CEO Tom Lix. “They’d been on a distillery tour a couple months before and wanted to know if we could help make hand sanitizer.”

With restaurants temporarily closed, Lix wanted to find a way to re-deploy his sales force team, who would typically be making sales calls to bars.

Through a $15,000, Small Business Recovery grant from Citizens Bank, Cleveland Whiskey was able to retain its sales staff and have them produce hand sanitizer.

“We’re an innovator in the whiskey space so we were already using some of the technology that we needed to make the switch,” says Lix. “We also utilized the distillery staff and had some help from Cleveland Clinic pharmacists to get us started.”

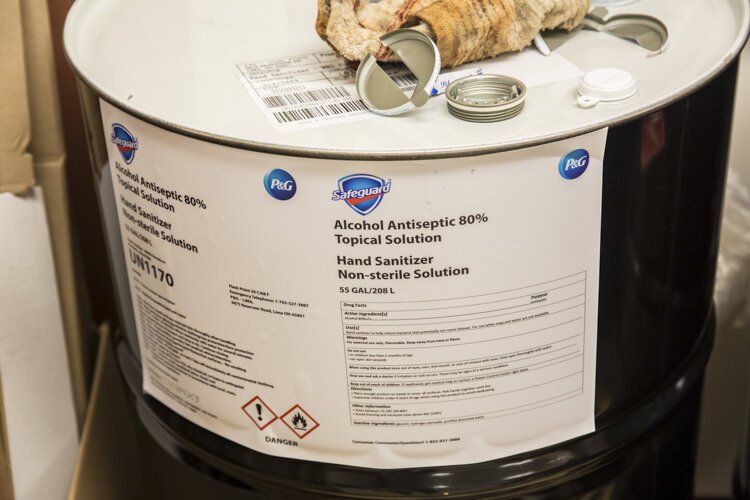

Cleveland Whiskey invested in a few new pieces of technology to improve their distilling process to create hand sanitizer. The Manufacturing Advocacy and Growth Network (MAGNET) and Columbus-based plastic container manufacturer Axium Packaging donated plastic bottles to fill with sanitizer.

Within three days of that Cleveland Clinic call, Cleveland Whiskey was producing and bottling hand sanitizer while keeping up with its monthly 10,000-bottle whiskey production.

“To date, we’ve produced and bottled approximately 12,400 gallons of sanitizer,” says Lix. The hand sanitizer was all donated to the Cleveland Clinic.

Challenges to Pivoting

However, not all PPE products were as easy to create, as masks, gowns, and sanitizer.

This was particularly for true for products requiring multiple components in their production—like face shields.

“Early on, we created a ‘hit list’ of what hospitals most needed” explains Brandon Cornuke, MAGNET ‘s vice president of startup services. “The top thing was face shields.”

MAGNET, which provides consulting services to manufacturers and start-ups, first tried to match the hospital’s needs with manufacturers that were already creating face masks.

“However, doctors kept telling us that the face shields in the market weren’t really what they needed,” recalls Cornuke. “The face shields were all disposable. They were also constructed with foam, which might actually help trap the virus.”

MAGNET is one of 2000 companies who has repurposed their operations and produce PPE for front-line medical workers.MAGNET then worked with a team of its engineers to adapt an open source design for hospital use, then made a call for companies that could make each subcomponent of the safer, COVID-resistant shield.

MAGNET is one of 2000 companies who has repurposed their operations and produce PPE for front-line medical workers.MAGNET then worked with a team of its engineers to adapt an open source design for hospital use, then made a call for companies that could make each subcomponent of the safer, COVID-resistant shield.

Within days, over 1,000 Northeast Ohio companies responded. Through a partnership with Jobs Ohio and the Ohio Manufacturing Alliance, MAGNET was able to help facilitate the creation of a whole new supply chain.

“We found one company that could do the injection molding, and one company that would create the rubber, and one company that cut the plastic” says Cornuke.

“Usually, it takes 12 to 18 months to create a new product like that,” said Cornuke. “We were able to do it in four weeks. Compared to normal times, that’s lightning fast.”

Cornuke attributes the lightning-fast innovation and product development of PPE to companies’ willingness to be open to new processes.

“One of the things that we saw was the openness to products that aren’t perfect but are good enough” says Cornuke. “The fact that [companies] would try things, experiment, and adjust was really important.”

Ethan Karp, President and CEO of MAGNET, emphasizes the role of company culture in driving the shift to creating PPE. He says that many of the companies responded simply out of a desire to “do the right thing.”

“The best thing by far is the knowledge that we are helping out in the midst of a pandemic, and NSA will continue to produce face masks as long as there is a demand,” says Farrow.

Lix, likewise, emphasizes the importance of company culture in driving hand sanitizer production.

“We have a simple mission statement that says that every day we make good whiskey and do the right thing. This gave us an opportunity to do the right thing, something important, something right here in our community.”

Positive long-term effects

Whether the companies continue to produce PPE items will depend on their ability to find new markets for their product once the pandemic ends.

“For many of the companies, [the switch to PPE] is not a sustainable pivot,” says Karp. He asserts that many of the manufacturers they work with did not go on to permanently produce those PPE items.

“But for others, they took our order and then went out and found other customers,” he continues. “They aren’t waiting on a handout from the state... They are asking, ‘How do I go and find a commercially viable solution for this opportunity?”

Many have started offering their products via the online Ohio Emergency PPE Makers Emergency Exchange, where businesses and individuals can search for products from local manufacturers.

However, even for those companies which do not go on to produce PPE permanently, the act of pivoting has itself provided long-term business benefits.

Mayen of Yellowcake Shop says the process sparked her to re-think her approach to design and customer service. While she doesn’t think she’ll make masks indefinitely, she does say it will affect how she does business in the future.

“Usually my customers can come into the shop and we can help fit clothing in-person. With online sales, I couldn’t fit each person for their mask. So, we had to invest in creating a really clear website and answer every single person’s phone call.”

“Moving forward, we definitely expect to do less travel shows and more online sales.”

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Journalism Collaborative that includes 16 Greater Cleveland news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland.