In gentrifying Ohio City, helping the ones who need it most

As Cleveland’s Rust-Belt-city-on-the-rise narrative continues to captivate outsiders and enable the city to attract big-ticket events like next year’s Republican National Convention, staffers and volunteers at nonprofits like the May Dugan Center in Ohio City maintain a front-line view of a more sobering story.

“They’ll be outside around 6 or 7 a.m., but we don’t open our doors until 8,” Larry Eason, head maintenance technician at May Dugan, said when describing the scene of the agency’s weekly fresh produce distribution.

Once those doors open, people get a ticket from the front desk and wait for their number to be called so they can get their hands on vegetables and fruit donated to May Dugan by the Cleveland Food Bank.

“We see people that are really hurting, and it’s grown in the last two years,” Eason said. “The city’s doing well, but we still have a lot of neighborhoods that are not.”

The building at 4115 Bridge Ave. gets busier on the fourth Wednesday of each month, when clothing, health screenings and others foods in addition to produce are distributed. Add in Narcotics Anonymous, counseling and other programs, and it’s easy for the Ohio City facility to average 500 people on those Wednesdays. That number is high when you consider that May Dugan only services residents from near west side neighborhoods of Cleveland, like Ohio City, Tremont, Clark-Fulton Stockyards and Detroit Shoreway.

Weekly fresh produce distribution at The May Dugan Center

Weekly fresh produce distribution at The May Dugan Center

“There’s a 45 percent poverty rate in Ohio City alone,” Executive Director Rick Kemm says. “We’ve got people who walk from Detroit Shoreway over here (to receive help).”

May Dugan services clients in five core areas: Basic Needs; Counseling and Case Management; Education and Resources; Health and Wellness; and education, support and resources to teenage mothers through its MomsFirst program. The Center received 17,433 client visits in 2014, with each core area doling out an increased amount of services compared to the prior year.

More than 10,000 of those visits took place on Food & Fresh Produce Distribution days. While the Center mostly attributes the whopping 75 percent increase to the offering of an additional produce day, that second day of service was only offered because of the need.

The May Dugan Center is a short drive away from the booming businesses of West 25th Street and close to renovated homes that helped the neighborhood’s median sales price jump by 23 percent from 2013 to 2014. However, the realities of its clients make the Center feel a world away from all of that.

Executive Director Rick Kemm and Deputy Director Andy Trares of The May Dugan Center

Executive Director Rick Kemm and Deputy Director Andy Trares of The May Dugan Center

“You have to admit the Ohio City neighborhood is reviving -- you can’t find any housing stock anymore, people are snatching up all these properties and renovating them, but there are still pockets of poor people that still live within the neighborhood,” Kemm says.

According to the City of Cleveland’s 2014 neighborhood fact sheet for Ohio City, which relies on data and estimates from the 2010 U.S. Census, 26 percent of families, or 1,063 households, earned income totaling less than $10,000.

In response to the basic needs around the community and other nearby neighborhoods, the Center provided about 400 health screenings, held more than 1,100 counseling sessions, enrolled 168 teen mothers into MomsFirst and took on 1,849 calls from 2-1-1 in the past year. Most aren’t surprised that those figures were overshadowed by feel-good Cleveland stories surrounding tech, sports and other industries.

“I’ve been in this field for 38 or 39 years, and that’s the way it’s always been,” says Roberta Taliaferro, May Dugan’s director of counseling and community programming. “I’m a native Clevelander, so I’m glad to see (positive news), and some of those things will be beneficial to everybody, but most people don’t want to hear about poor people or mentally ill people.

“That’s always been the case.”

How it started

Kemm says only small bits of the May Dugan Center’s history have truly been told and presented to the public before. As he and his staff work on the early parts of a to-be-determined historical project, they've realized they’re trying to fight poverty in many of the same ways its founders did in the late 1960's, when the nonprofit was first incorporated as the Near West Side Multi-Service Corp.

A national request for proposals from President Lyndon B. Johnson’s office accompanied his launch of the War on Poverty in 1964. In response, a group of near west side residents worked with city officials to craft a funding proposal to construct what is now the May Dugan Center. Kemm says the facility outlasted its counterpart— another multi-service center in the Hough neighborhood that received War on Poverty funding.

“When they celebrated the 50th anniversary of the War on Poverty, we said, ‘wow, we’re still doing this,’ but it’s different,” Kemm says. “People have more access to services they may need.”

Much like the food distributions that go on at the May Dugan Center today, the building was known as a food crisis center when its doors opened in 1975. Starving citizens and those in emergency situations rang a doorbell to receive food that was collected by churches and other donors. The actual May Dugan was the daughter of Irish immigrants who wanted to help her neighbors overcome the financial hardships her family had experienced. At one point, Dugan, the owner of a few local taverns, clothed, fed and housed more than 20 homeless people in her attic, garage and wherever else they would fit.

Much like the food distributions that go on at the May Dugan Center today, the building was known as a food crisis center when its doors opened in 1975. Starving citizens and those in emergency situations rang a doorbell to receive food that was collected by churches and other donors. The actual May Dugan was the daughter of Irish immigrants who wanted to help her neighbors overcome the financial hardships her family had experienced. At one point, Dugan, the owner of a few local taverns, clothed, fed and housed more than 20 homeless people in her attic, garage and wherever else they would fit.

“She was always down at City Hall, complaining to elected officials that we need more jobs,” Kemm said. “She did that through the ‘30s, the ‘40s, the ‘50s and the ‘60s, until she was too old. When the funds were approved to build this facility, that’s when they petitioned to name it after her when she died.”

What May Dugan Can Do

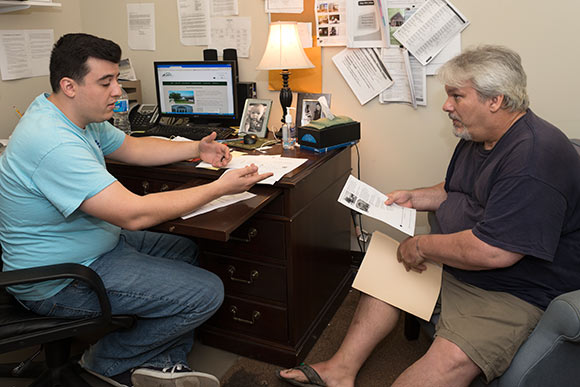

The May Dugan Center prides itself on offering “wrap-around” services, or a variety of programs made possible by a diverse pool of partners, donors and volunteers. Within its core areas, the May Dugan Center today collaborates with entities like the Cleveland Metropolitan School District, the West Side Catholic Center, the LGBT Center and more under an array of contracts and signed memorandums of understanding. Tenants include Refugee Response, six Cuyahoga County Adult Probation officers, and the Council for Economic Opportunities in Greater Cleveland’s Home Energy Assistance Program (HEAP).

“What’s unique about May Dugan is we are preventing homelessness,” Kemm says. “May Dugan is working with people who want to pull themselves up, people who have experiences with bad luck or they lost their jobs, but May Dugan has the resources to help people get themselves back on their feet.”

In some cases a confidence boost can be the difference. Samantha Mallory needed just two and a half months of the May Dugan Center’s GED course to help her find a job. In fact, it was the same soldering assembly job a Cleveland-area factory previously denied her because she didn’t have a GED diploma.

“They brought me back in for a second interview,” Mallory says. “It was more about being dedicated to getting it.”

The 28-year-old says her fear held her back more than her trouble with math. Mallory had already been laid off, and when she tried to take GED courses before, she went to a much larger class elsewhere that lacked the individualized attention she would go on to receive at May Dugan.

“It was something that I always put to the side because I was scared to do it,” the mother of one admitted, “but I’m glad I did it. I wasn’t going to make as much money as I am now."

“They basically told me to stop looking at it as numbers and stop overthinking it. Any time I had a problem, (the instructors) were there.”

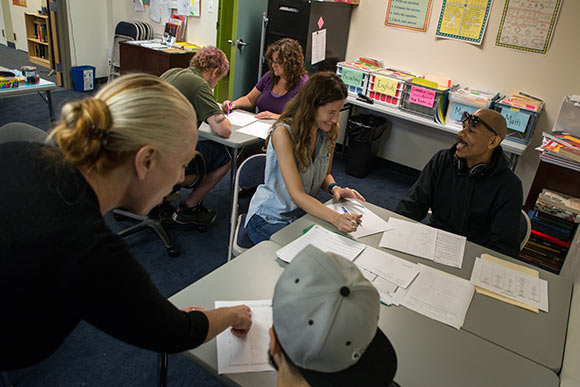

Through May Dugan’s Education and Resource Center, about 270 adults took courses on basic literacy, workforce development and trauma-infused instruction, which pays attention to the mental and emotional barriers that hold some people back from bettering and sustaining their lives.

The Center’s services ‘wrapped around’ to nearly every facet of life. HEAP provided utility assistance to 670 clients last year, while 50 clients received HIV/AIDS counseling. During the holidays, 12 sponsors participated in the Adopt-a-Family program, providing gifts and necessities valued at $7,800, according to the May Dugan Center.

The Kemm Influence

With prior experience raising funds at Eliza Bryant Village and overseeing fund distribution at United Way of Greater Cleveland, Kemm was ready to lead a nonprofit by 2008. However, the Great Recession ensured that he would have to adjust on the fly.

Shortly after getting the job, the board informed him of a $200,000 hit in funding. He also dealt with what he described as a “neglect in maintenance and staffing morale,” as well as an expiring lease with the city and foundations that had become put off with the way the May Dugan Center was being operated.

Despite conceding that “it was just a mess,” Kemm didn’t let the early troubles thwart his vision or that of the late May Dugan.

“This building was meant to be an anchor on this corner so that poor people know where to go for help,” he says.

Kemm says he had to regain trust with funders and justify the Center’s requests with better outcomes in his first couple years at the helm.

“There were local foundations that said, ‘oh, no, Rick. May Dugan is no longer on our radar screen,’” Kemm recalled. “People were telling me this. Three different foundations that I had built good relationships with … We needed to rebuild programming so that we could say, ‘we helped 50 people find a job instead of three the year before.’”

Outcomes in 2015 look favorable, too. For instance, Counseling and Community Service clients reported consistent decreases in their symptoms over time. Thirty-nine percent of the clients reported always or often feeling interference from their symptoms in their initial survey. That percentage dropped to 31 after six months, and to 0 percent annually.

One of May Dugan’s biggest breakthroughs of the past year happened when it earned accreditation status from the Commission on Accreditation for Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) and certification from the Ohio Mental Health & Addiction Services Department. Those achievements enabled May Dugan to bill Medicaid, Medicare and insurance companies for its services. That brought $85,500 in new revenue last year, narrowly eclipsing the $85,000 goal that May Dugan had set for itself. The Center is already halfway to its 2015 goal of $157,000 in such revenue.

“A lot of community health centers have either crumbled under the pressure of trying to get money or meeting productivity goals, but I think because Rick is good at getting foundations involved, it’s just a different mind set,” Taliaferro says. “We do truly make our clients the center. They are the ones who run the agency, and we wouldn’t be here without them.”

That client focus is what has Kemm on the hunt for a capital improvement grant to get work done on the restrooms. It would complement a recent City of Cleveland grant for more than $100,000 that will repair the leaky roof and level the sidewalk. It’s also what has he and his staff determined to turn around a two-year cycle of expenses outweighing revenues, including last year’s difference of $119,119. To combat that, Kemm says staffers have identified grants like funding from the Victim of Crimes Act. May Dugan also received a personal invitation from an official at Bank of America to apply for a $200,000 grant.

Kemm believes that type of funding will help the Center create the type of change it has sought for more than four decades.

“People don’t want to be homeless, people don’t want to be dependent on government funding,” Kemm says. “It makes me feel really proud that we continue to be innovative in identifying the necessary resources that we need to help these people."

.jpg)