The very Irish history of Cleveland's west side philanthropy

Charleen Reynolds-Cuffari can make anybody understand the kind of woman her grandmother was before uttering a word. Asked to describe the late May Dugan’s personality, the Kamm’s Corners resident narrows her eyes and raises a tightly clenched fist, forcing you to catch her drift.

“I had the tough grandmother,” Reynolds-Cuffari says. “She ruled with an iron fist.”

May’s parents, James and Annie, instilled that toughness in their children after emigrating from Ireland in 1883 and settling in Cleveland after stops in Quebec and Detroit. May had three brothers, and at least two other siblings who died during infancy.

May’s parents, James and Annie, instilled that toughness in their children after emigrating from Ireland in 1883 and settling in Cleveland after stops in Quebec and Detroit. May had three brothers, and at least two other siblings who died during infancy.

Maintaining a bit of grit became a necessity for May by the time she reached her 30s. Her first husband, William Reynolds, and father both died in 1928, leaving her to run the family business and depend on her oldest son to help raise four small children. Another child had already died at the age of two. Then the Great Depression arrived just one year later.

However, none of those factors overtook May Reynolds Dugan’s renowned reputation as one of the greatest givers Cleveland has known. Dugan (who largely dropped her married name of Reynolds) wasn’t the endowment-and-grant type of philanthropist you typically read about today. Instead, she was the type to offer her home as a place to stay for one, two or even 25 community members at a time.

“Somebody might knock on the back door, looking for something to eat, and she always had something for everybody,” says Patrick Reynolds, Dugan’s grandson and president of the May Dugan Center’s board of directors. “That wasn’t uncommon.”

Dugan’s grandchildren and other living relatives struggle to think of a time when she wasn’t concerned about the community’s welfare. Her fight for others’ well being is what led to a group of Clevelanders and Dugan family members to petition the city for the Near West Side Multi-Service Center to formally become the May Dugan Center in 1974, despite multiple suggestions to name it after local politicians and other more recognizable figures.

Only a few locals truly knew about Dugan’s brand of community service, but the Center’s board sought to change that.

“You know how you name things after so-called important people that have a name already and are in the spotlight? Well, (Dugan) was just a regular person who raised her family,” says Mary Rose Oakar, one of the Center’s founding board members and former Cleveland councilwoman who would later become Ohio’s first Democratic Congresswoman.

“It was about time. Everybody plays a role in a community. You don’t have to be some big dude to (deserve recognition)," she adds. "Lots of times, it’s people who do a good job and raise a family.”

The change became official after May Dugan died in the 1970s, when, as family members recall, she was 84.

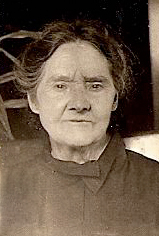

May Dugan"You give. You don’t expect to receive."

May Dugan"You give. You don’t expect to receive."

Reynolds-Cuffari spent most Saturdays of her youth at Grandma Dugan’s house, which was on the same lot as Dugan’s Tavern. Today, the parking lot of Spice Kitchen + Bar sits on that land.

Reynolds-Cuffari’s father, Iggy, who is believed to have initially suggested the Center change its name to honor May Dugan, would drop the young girl off on Saturday mornings and pick her up on Sunday night. Reynolds-Cuffari would spend much of the first day cleaning her grandmother’s house, while Sundays were spent accompanying her at St. Malachi Parish for Sunday service. At some point during those weekends, Dugan would send her granddaughter to pick up goods from the old Isabella Brothers Bakery on West 69th Street.

Meanwhile, a young Patrick Reynolds would ride his bike from his family’s home near West Boulevard and Lorain Avenue to his grandmother’s home to spend summer days with her. Both grandchildren shared the same lasting image from those days: May sitting on her front porch, engaging with a steady stream of visitors, including many who were unashamed to come with their hands out.

“She’d have a pocket full of change,” says Reynolds-Cuffari, a retired stenographer from the Cleveland Police Department. “She’d help anybody. Her motto was: You give. You don’t expect to receive.”

In addition to neighbors in need, it was common to see people such as late U.S. Rep. Michael Feighan standing in the yard talking to Dugan, recalls Reynolds. However, those conversations would revolve around how Dugan could become a governmental conduit for a voiceless friend and not about how she might help herself.

While neither Patrick nor Charleen say they witnessed their grandmother opening her doors to 25 penniless people - a story shared by the May Dugan Center and others - they both find it entirely plausible. The same goes for Margaret Lynch, the executive director of the Irish American Archives Society whose great grandfather was the nephew of Annie Dugan. Lynch believes May Dugan’s propensity to give back amid adversity was rooted in a common, Irish practice, dating back to the 1880s when the Dugans and many other families emigrated on “famine ships” from areas like Achill Island, Ireland, to ports in Quebec and Boston.

“Because of this chain migration situation, there were interrelated families – McManamon, Gallagher, Dugan,” Lynch says. “(My great aunt) didn’t emigrate until 1921, but they ended up in a household with 21 people on Whitman in Ohio City … There was a lot of coming and going. If they didn’t have money, she wouldn’t ask for it," says Lynch. “That’s how people did things.”

The tradition among immigrant neighborhoods at the time, notes Lynch, was one of neighbors looking out for each other, helping out with whatever was the task at hand, including anything from immigration paperwork to making lunch for nearby factory workers.

“May was the inheritor of this," says Lynch, "and that’s how she was brought up. I don’t know the specific details of those 25 people, but I’m sure she did that.”

By the time May turned four, the family moved to what was known as The Angle neighborhood of Cleveland on Hanover Street, which is present-day West 28th Street. Her parents ran a saloon, setting an early example for both May’s entrepreneurial and philanthropic ways. It also galvanized the idea that a tavern could and should be a community center.

“A bar is a bar serving alcohol, but it’s also a community center,” Lynch says. “It’s also a place where people were looking for help of different kinds. My great grandfather took over the Dugans’ bar in The Angle (after they moved to West 58th Street) and he would write letters for people that wanted to write back to their families in Ireland. My grandmother would take them to the post office."

She continues: “I don’t know for sure if the Dugans did that (sort of thing) for other people, but they were a leg up on some of the other people (who emigrated from Ireland)," adds Lynch. "I think, given May Dugan’s later history as a community person, I’m thinking this practice started with her parents with helping people out.

“They were people who figured out more quickly than some of their peers how to navigate in this world. And they were in a position to help other people.”

May DuganCarrying Out Her Legacy

May DuganCarrying Out Her Legacy

May Dugan Center's executive director Rick Kemm just loves when visitors ask that famous question.

“Was May Dugan really a person?” a potential tenant asked Kemm during a recent tour of the Center's vacant, third-floor space. This question allows Kemm to discuss Dugan’s background and that she was still alive during the building’s construction. Such conversations inevitably turn to the symmetry between Dugan’s neighborhood philanthropy of the 1920s through the 1960s and the health and human services the Center that bears her name has been providing for the nearly 50 years that followed.

“I love telling that story because not only is it important to tell what we’re doing today – what our mission is and how we fulfill our mission through our five core programs," says Kemm, "but to even go further back because we’re really living May Dugan’s legacy.”

Reynolds and Kemm agreed that May would be particularly proud of the center’s mental health and education programming. Her grandson still remembers her urging him to keep his nose in his books and learn even more than she had.

“She helped feed, clothe and house people,” Kemm says. “To this day, we’re still helping feed, clothe and find housing for people, and helping people find jobs.

“It’s wonderful to be able to live May Dugan’s legacy.”

This story is the first of a Fresh Water series supported in part by the May Dugan Center.

.jpg)