Help Wanted: Shortage of mental health workers stresses agencies, patients

Unprecedented demand and a sparse employee pipeline are adding stress to Ohio’s already strained behavioral health system.

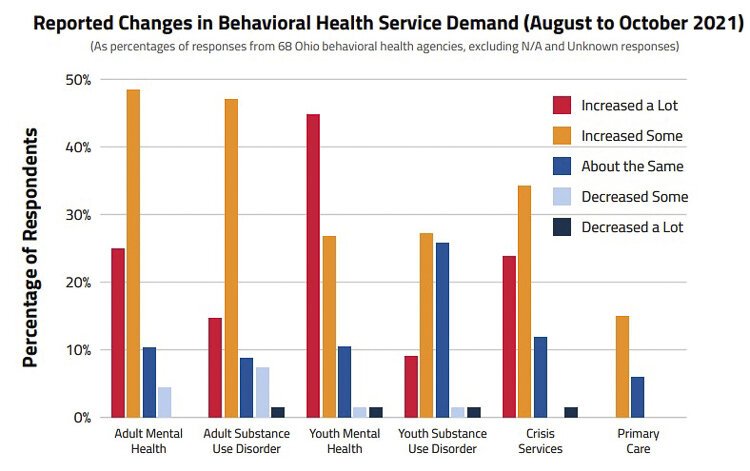

From 2013 to 2019, demand for behavioral health services rose 353% statewide, according to data from the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. Demand spiked again in 2021—with providers reporting a 70% hike in need for adult and youth mental health services

and a 60% increase in the need for addiction services.

“Demand is definitely up,” said Eric Morse, CEO The Centers in Cleveland, a nonprofit that offers an array of services including case management, counseling, psychiatric services, and substance abuse treatment. “It was high before COVID, I think. COVID has just made it even worse.”

“Demand is definitely up,” said Eric Morse, CEO The Centers in Cleveland, a nonprofit that offers an array of services including case management, counseling, psychiatric services, and substance abuse treatment. “It was high before COVID, I think. COVID has just made it even worse.”

There are many reasons for the shortage, says mental health professionals.

Workers and clients got used to telehealth appointments, and it’s difficult to get workers to want to go back into private homes where much of mental health assistance takes place, Morse says. Low pay also discourages new people from entering the profession, and existing workers get burnt out as caseloads go up—making them more likely to switch careers or retire.

Justin Larson, who oversees support programs for Thrive Peer Recovery Services for those suffering mental health or substance abuse disorders, says the pandemic hindered his ability to find new workers.

“Sometimes it’s been difficult to find peer recovery supporters that actually want to work in a hospital, [especially during Covid peaks],” he says. “It was kind of difficult to get people to want to work in an environment where people were coming in that may be positive for COVID-19.”

Higher demand and a lean staff mean longer waits for services, which could be dangerous for patients.

“I can’t even imagine—that could be a potential death,” says Kelitha Bivens-Hammond, a peer supervisor at Thrive. “Honestly, if we had to turn someone away, they could go back and use and overdose. That’s my first thought. This is a life-or-death situation.”

Longer Waits, Higher Risks

Bivens-Hammond knows first-hand how dangerous addiction and mental health issues can be. Before becoming a peer recovery counselor, she struggled with her own addiction. She began using alcohol at age nine. At 21, she started going to treatment centers. After 27 attempts at sobriety over about 20 years, she got help from Thrive.

“I know I would have died. I know that for a fact,” says Bivens-Hammond. “That’s where I was headed. I had already been institutionalized. I had already been to jail. There was nothing left for me, except to die.”

Kelitha Bivens-Hammond works for the nonprofit as a supervisor and counselor at St. Vincent Charity Medical Center in Cleveland.Bivens-Hammonds helps up to 10 people a day at Thrive’s location at St. Vincent Charity Medical Center in Cleveland. Thrive also has locations at MetroHealth, University Hospitals, the Cleveland Clinic, and elsewhere around the state.

Kelitha Bivens-Hammond works for the nonprofit as a supervisor and counselor at St. Vincent Charity Medical Center in Cleveland.Bivens-Hammonds helps up to 10 people a day at Thrive’s location at St. Vincent Charity Medical Center in Cleveland. Thrive also has locations at MetroHealth, University Hospitals, the Cleveland Clinic, and elsewhere around the state.

A shortage of behavioral health services could add pressure to other systems, The Center’s Morse says, adding that people may need to go to the hospital or visit an emergency room to receive services. If an incident occurs, police may be called—leading to criminal charges or further damage to someone’s mental health.

“We know statistically that the suicide rate and overdose rate continue to get worse,” he says. “I would say if we had better capacity to help people that those numbers—I would hope—would go down. That would be ultimately what I would hope. If we had good access to health, there would be less death.”

Lots of Turnover

Hiring and retention are the main obstacles to meeting the demand, mental health care providers say.

“The number of providers who want to enter the community behavioral health space is still a challenge,” says Morse. “The job market is obviously very employee-friendly right now. Even though we have increased our wages pretty substantially over the last two years, we’re still competing with jobs that are for sure a lot less stressful than doing the work here. Particularly among case managers, where we typically hire people with a bachelor’s degree in psychology, sociology, or social work. People with those degrees can get higher-paying jobs that are less stressful.”

Morse employs 28 case managers. He’s budgeted for 40, and he says he can use 60 to 80 because demand is so high. Each case worker serves around 100 people. Median salary is $40,000 annually.

“This is another reason why we have turnover,” he says. “The job is really, really hard. The caseload should be around 40 to 50 because these are people who need a lot of attention. Because of the staffing shortage, caseloads being at 100, it really changes the work. It changes your ability to respond to the needs of everyone you’re serving.”

Luke Church, a team lead for Thrive at the MetroHealth location, says the system definitely needs more people. “I don’t think that’s for lack of trying,” he says.

The difficulty lies in finding the right people with the right background, credentials, temperament and passion.

“It’s a niche sort of employment market,” says Church. “With an employment shortage on top of all those variables, I think it’s tough to find people. There’s just not enough bodies necessarily that are able even to apply.”

Five peer counselors report to Church. “Two more people would make it more comfortable,” he says.

Paul Bolino, CEO of the non-profit Community Counseling Center in Ashtabula County, is looking to fill 11 positions across his agency, representing a 10% workforce shortage.

“We’re short-staffed in multiple programs,” he says. “A lot happened during the pandemic. As the stress built, people made different choices and made some changes. We were not immune to the great reshuffle.”

Bolino says attrition is also a factor. “We also have a number of private practitioners in the area that are retiring,” he says. “They’re leaving the workforce, and that’s hard because when you’re dealing with commercial insurance that requires a higher license—an independent license—and years of experience, we’re not backfilling those positions quick enough. So, when those providers leave the networks, leave the area, or leave the workforce, the younger clinicians don’t have time to make that up.”

Bolino says the trained workforce has to be built up.

Building a Pipeline

To that end, Community Counseling Center has started an internship program. Bolino also points to a planned new social work program at Kent State University’s regional campuses.

“We said, “let’s bring in people who are new to the field, [who] are students, whether traditional or nontraditional students,” he explains. “Let’s bring them in as interns, develop them in our system, then hope through our engagement with them during that time we get them to stick around and be part of our organization for the longer term.”

The Center’s Morse is trying a similar tactic.

“We’re looking at how we can be more present in the schools—to really hype this up as a good career,” he says. “You can start as a case manager, then get your master’s degree and then move up to being a therapist. Then move into management. It can be a good career for someone, not just a job. We want to promote that.”

Even if the pipeline issues are solved, salary will likely remain an issue.

“Obviously, there’s a point in which if we could get the salaries high enough, I think it would be a more appealing job and maybe we’d have less vacancies,” Morse speculates.

The number of providers who want to enter the community behavioral health space is still a challengeBolino agrees that good salaries would be an incentive in attracting workers. “We’ve got to continue the process of making these jobs attractive and making them pay enough with solid benefits so you can have a career in that position,” he says. “There’s just so many things at work. But if we don’t, we will serve less people, and I don’t think we can afford to do that with how heavy things are right now.”

The number of providers who want to enter the community behavioral health space is still a challengeBolino agrees that good salaries would be an incentive in attracting workers. “We’ve got to continue the process of making these jobs attractive and making them pay enough with solid benefits so you can have a career in that position,” he says. “There’s just so many things at work. But if we don’t, we will serve less people, and I don’t think we can afford to do that with how heavy things are right now.”

Ohio legislators also see the need. In May, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine announced that the state will commit $85 million to strengthen the behavioral health system. The money will be used to create scholarships and paid internships to lure new employees into the field.

“More options for entering careers in behavioral health will mean more new clinicians to help patients in need,” Ohio Council of Behavioral Health & Family Services Providers CEO Teresa Lampl said during the announcement.

That’s welcome news around the state.

“It’s going to take more than a village,” Bolino says. “It’s going to take a state and beyond to address this.”

Tiffany Alexander is a writer and educator based in Cleveland.

This story is a part of the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative’s Making Ends Meet project. NEO SoJo is composed of 18-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland.