New Leaf Project study shows one-time direct cash transfers positively impact the homeless

Facing the challenges and frustrations of being homeless in Vancouver

Facing the challenges and frustrations of being homeless in Vancouver

Thousands of people experience homelessness in Northeast Ohio every year. But what if these people were given money? Money that they could use to dig their way out of poverty and turn a new leaf?

Co-Author Jeneane Vanderhoff and her husband AdamWhen poverty and homelessness beat reporter for The Tremonster Jeneane Vanderhoff (who is currently experiencing homelessness along with her husband, Adam) was considering reporting on any existing solution that might help alleviate the problem of homelessness in Northeast Ohio, she seeing an interesting study. “I read a study—I think it was Canada—they just recently gave homeless people $7,500 and saw how the people spent it," she recalls. "It basically got them out of homelessness. It did quite a bit to turn their lives around; they really didn’t waste the money—it’s a recent study.”

Co-Author Jeneane Vanderhoff and her husband AdamWhen poverty and homelessness beat reporter for The Tremonster Jeneane Vanderhoff (who is currently experiencing homelessness along with her husband, Adam) was considering reporting on any existing solution that might help alleviate the problem of homelessness in Northeast Ohio, she seeing an interesting study. “I read a study—I think it was Canada—they just recently gave homeless people $7,500 and saw how the people spent it," she recalls. "It basically got them out of homelessness. It did quite a bit to turn their lives around; they really didn’t waste the money—it’s a recent study.”

The Tremonster's research led Vanderhoff to The New Leaf project in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, which recently published the study. The project demonstrated that money from one-time cash transfers was spent wisely and provided stability in the lives of individuals experiencing homelessness.

In Northeast Ohio, homelessness statistics reflect an alarmingly large problem for the region’s population and economy. The Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless (NEOCH, which supports the Cleveland Street Chronicle (a NEOSOJO member outlet and partner on this report), published census data that showed about 23,000 people experiencing homelessness in 2018 in Cuyahoga County; and Akron Citizens Coalition for Emergency Shelter Services (ACCESS, Inc.) published data from the Point in Time count, which found 546 homeless individuals in Summit County on one night in January 2019.

In a 2017 study, the National Alliance to End Homelessness found a chronically homeless person costs the tax payer an average of $35,578 per year, and a homeless person in supportive housing costs on average $12,800 per year.

Vanderhoff was curious if the solution in Vancouver could be applied to help reduce homelessness in Northeast Ohio. In January, Vanderhoff was able to reach Claire Williams, co-founder and CEO of Foundations for Social Change, which launched the New Leaf project.

Here is Vanderhoff’s conversation with Williams.

Jeneane Vanderhoff: Claire, could you start off with a basic explanation of the New Leaf project?

Claire Williams: The New Leaf project was the world’s first randomized, controlled trial to test the power of direct cash transfers with people experiencing homelessness. What that looks like is we gave 50 people who were recently homeless a one-time cash gift of $7,500. That amount was benchmarked against the 2016 income assistance rate (or the welfare rate, I think you call it in the United States)—so, people basically got a year of income assistance in a one-time lump sum, which was directly deposited into a no-fee checking account with our local credit union.

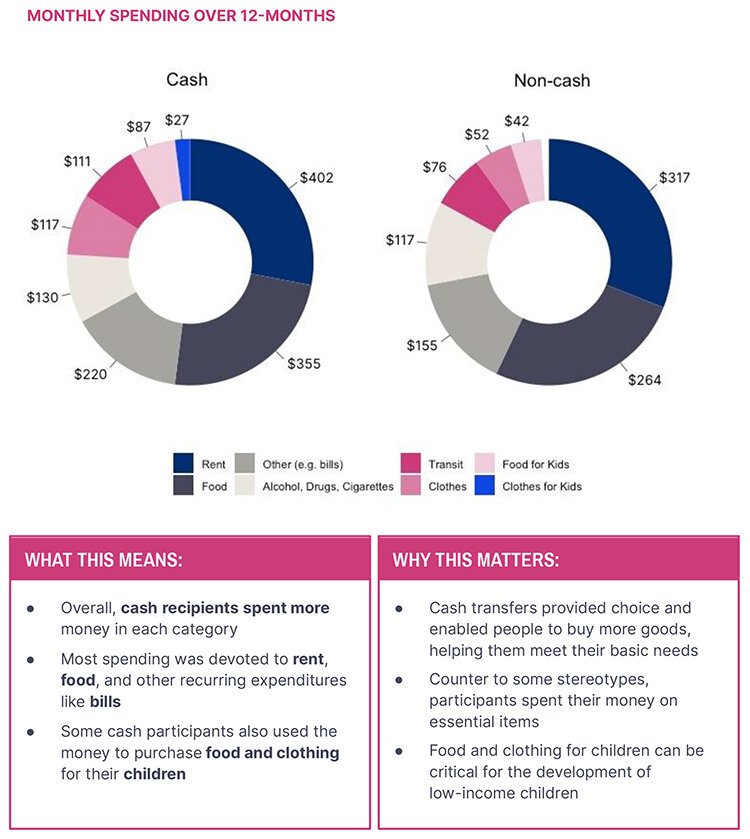

Then, we collected data on people over the course of 12 months to two years, depending on when people were enrolled. What we saw is that—very quickly—people in the cash group moved into stable housing faster, they spent fewer days homeless, and they retained over $1,000 through 12 months—which is incredible in a place like Vancouver, in the Lower Mainland, it’s really expensive to live here.

We saw that there was an increased spending on food, clothing, rent, and that people were achieving greater food security. Then, what I call the darling of our data set: we saw that people made wise financial choices with the money, so we saw a reduction by 39% in spending on drugs, alcohol, and tobacco. I call this “the darling of our data set” because it just flies in the face of the mainstream cultural narrative around people living in homelessness or poverty that they can’t be trusted to make wise financial choices, where in fact our data shows that is not the case.

If you think of cash-based interventions on a spectrum, at one end of the continuum you would have something like what we’re doing (which is a one-time cash transfer); the other end of that continuum would be a universal basic income (where everyone is getting a certain amount of money to cover their basic needs). Right now, we do not have a basic income in Canada, but I think there is an incredibly powerful rationale for introducing something like that—especially based on our data and the growing data from studies across North America.

People, we need money—we live on a monied planet, so we need money to meet our basic needs. In Canada, when the pandemic hit, we as a federal government, offered everybody initially $2,000 a month, which, to me, communicates that’s the bare minimum you need to exist in society. So why are our governments not providing that support? Poverty is not cheap. It’s not free to maintain the status quo, it’s incredibly expensive, and that’s on top of the human suffering.

Vanderhoff: What’s the difference between Universal Basic Income and your one-time cash transfer program?

Williams: We are not a Universal Basic Income-driven organization—we are a big proponent of it and a big supporter of it, but Universal Basic Income is a huge undertaking. It’s something that’s undertaken by a government.

We have people both here in British Columbia and in Ontario. There are policy makers and academics who are performing options analysis to explore whether it’s viable, and it could take years to implement a Universal Basic Income. Whereas, what we love about direct cash transfers is that they are an elegant and simple approach to poverty reduction and, in this case, ending homelessness—we’re empowering people to move beyond homelessness. We privately fundraise the dollars and we can put money into people’s hands very quickly.

Vanderhoff: Did you see an increase in Vancouver homelessness with the COVID-19 pandemic?

Williams: I have not seen any numbers, Jeneane, but absolutely—there’s no way that we are not seeing an increased number of folks entering homelessness. I know just from news reports that a number of people are living in economic precarity in Canada. Rents have gone down, I think, in Vancouver by about 12%, but the cost of property and the cost of living has not decreased. I know it’s more expensive to get groceries now, so when people are facing reduced working hours or full unemployment altogether, we’re just going to see people entering homelessness more often. I haven’t seen any proven statistics yet, so it’s more anecdotal and a hunch as opposed to anything I’ve seen in the news.

Vanderhoff: In my research, I saw that the New Leaf project helps with shelters and other Vancouver homeless support—did you pick people from shelters? Did people sign up? How were the original program participants picked?

Williams: Yes, we worked with four different shelter organizations. Neither myself nor anybody on the team had experience working with people who are experiencing homelessness, so we partnered with existing organizations because they have a wealth of knowledge and expertise, and we worked with them to identify people in shelter who might be a good fit for our program.

We sat down with them; we ran them through an interview and some screening questions. Once people were successfully screened, they were randomly assigned to a “cash group” or a “non-cash group.” This is a randomized control trial, so it’s all done by a computer. It randomly selects who’s in a “cash group” and who’s in a “non-cash” group.

Vanderhoff: Do you think that your country’s perspective on homelessness differs from our perspective on homelessness? I personally experience homelessness—I’m still in the midst of it—I came from a middle-class family. I’m 40 years old. I went to college, and then to see how people looked at me and treated me…I felt so at home when reading on your website that you’re doing something like this, I’m just so amazed that I just want to thank you. Do you feel Canadians see homeless people in a different way than we do in the United States?

Williams: I absolutely do not, no. First of all, I want to acknowledge what you shared, and I’m sorry for those experiences. It’s hard. I know, just from the folks we’ve talked to, when you are experiencing homelessness, people often feel invisible, they feel like they’ve had their dignity taken away, so I just want to express my heartfelt compassion for that experience.

Do I think that Canadians regard homelessness differently than our American brothers and sisters? Absolutely not. I think there are pockets of compassion, both here in Canada and in the US, but by no means do I think that we are morally superior in how we regard people who are homeless.

Vanderhoff: So, you guys have citizens who don’t like this program—that stand up against it?

Williams: Oh, absolutely. Since we’ve gone public, we’ve actually had more interest from American organizations than we have from within Canada.

Vanderhoff: Wow.

Williams: There are a lot of cash-based projects going on in America—Americans, I find you’re much more open-minded, you’re much more willing to take risk. And then, the harmful, negative stereotypes—they are as prevalent in Canada as they are in the U.S. I think it’s natural, when you first tell people you’re going to hand out a large sum of cash, people are a little bit in shock. They’re in awe. We’re very precious about money here in North America.

We have this kind of puritanical attitude that everybody—one, has started from the same starting point, or given the same privilege; and two, if you just pull up your bootstraps and work a little bit harder, you, too, can get ahead. So, I think people are initially shocked and they say, “Oh my gosh, you’re giving out a huge amount of cash!” But I think that just comes from the cultural narrative we’re steeped in, as well.

Then, when it comes to homelessness and poverty, we love to tell the story about the person that is homeless is that old guy with the beard who’s rifling through the garbage and he’s lazy and he just drinks all the time—but that could not be further from the truth.

I think there’s a real education component that’s missing from the conversation around homelessness, as well as any humanizing—and just realizing that homelessness [is] not because people lack character, it’s because they lack cash or they lack a support system.

We didn’t all start from the same place. So, I try to empathize with people who are initially like, “You can’t just give away money!” Then we have a conversation and I say, “Actually, you can.” In some cases, people are more interested in the story that is painted in the media—that we see painted in Hollywood movies and literature around homelessness and poverty—but then there are other people who see our data and say, “Oh my gosh, this actually works!”

And on top of reducing suffering and empowering folks to move beyond homelessness, it actually saves money. So, why the heck aren’t we doing this?

Vanderhoff: Could someone be doing this here?

Williams: Absolutely. There are a number of cash-based projects—people are testing Universal Basic Income in Stockton, California, they’re testing it in Oakland, California, as well. There’s the Mississippi Magnolia Mother’s [Trust] Project where they are giving cash transfers to single moms, and then we are having some initial conversations with organizations and a possible funder (I can’t say their name right now) around partnering with U.S.-based organizations to do something like this, there.

I think Jack Dorsey, as well, who is the founder of Twitter [is working on it]. I think he has given $10 million or more to fund cash-based projects. So, there’s money there.

Vanderhoff: Where do you feel your own planning for the Vancouver New Leaf project fell short?

Williams: We are the first people to do it, so we didn’t have a model to work off. There were lots of lessons learned out of our project.

One lesson we learned was around recruitment: I thought it would be easy to recruit people, but we were going into shelters with the assumption that the right people were going to be in the shelter when we were in the shelter (at the same time) and that’s just not realistic.

Homelessness is a full-time job; you’re not just sitting around waiting for somebody to show up in a shelter. It was a little more structured than just walking in and saying, “We’re here,” but it had its limitations. We would pre-identify people, so I would tap you on the shoulder and say, “Hey, Joe, you’ve been identified as a possible candidate to participate in this survey" (at the time, people didn’t know what the project was about).

We would tell a potential candidate “You will receive $20, and you need to be in the shelter on Thursday at noon.” And then our candidates would forget to be in the shelter on Thursday at noon because they would be out looking for a job or were stuck in a line to fill in some government form.

That inspired us to create an online recruitment platform for our next extension project, which will allow people to apply on their own terms on their own time, as opposed to us demanding that they be in the shelter when we’re there. We’re looking at ways to streamline our process, to democratize our participation in our project and increase our efficiency.

Vanderhoff: I get it, Claire. You might hear things from the church community or people in the homeless community. You might get word about people that might fit, and you might go and set up an appointment, but it was just hard to get into their lives because they were—homeless people are really busy—they’re out on the streets looking for work all the time.

I can see where it would be hard to get homeless people to fit into your schedule. We’ve had people looking for us for weeks like that. I can understand how that problem would make it hard for your program in the beginning.

Williams: Yeah, we didn’t announce it as the project that gives away money, they just knew that it was a research project. And life happens, right?

Vanderhoff: How did you pick out those original recipients?

Williams: We worked with four specific shelter organizations and then identified people that they thought would be a good fit. [Now, with New Leaf Project online registration], instead of going into a shelter and requiring people be there to answer our screening questions, they can just log on to our platform and answer the screening questions online at a time that is convenient to them.

Vanderhoff: The hotel they have me and Adam in—they book rooms here at $139 per night. I’m sure, with COVID-19, I know they’re getting a deal, but they must be paying $40 per night or more. Think about that—how many rooms they have; they have to have roommates, but still, that’s expensive in itself. We could have an apartment for much cheaper than that, you know?

With the planning, I can just imagine getting that sum of money—I got a COVID-19 [pandemic relief] check, and I wanted to get a cheaper car—that is just enough money, maybe, to put a down payment on a car, get your credit, if you had none, restarted.

Did the homeless recipients think about it before they spent the money? They thought about it, didn’t they—because now it’s your money?

Williams: Oh, absolutely, yes. It gives people a choice. They get to choose how they move their lives forward. We all want choice; we don’t want to be treated like children. It gives people agency, and I think just showing that we believe in people made a difference in peoples’ lives.

If you look at our Statement of Impact, you’ll see there is a graph on a cost-benefit analysis. Not surprisingly, to Jeneane’s point, putting people in shelter or hotels—it’s not cheap.

It’s more in many cases than you would pay to have your own apartment. Over the course of the cash transfer, we saw that there was a savings of $8,600 per person that received the cash transfer—primarily from reducing their reliance on the shelter system of care.

Once you subtract the cost of the cash transfer, that’s a net savings of $600 per person. That’s just measuring obvious things; not necessarily looking at reduction in crime because our group isn’t big enough. Nor are we looking at things like chronic health issues that a lot of people develop when they’re in homelessness.

There are massive costs beyond what we just see in that moment when it comes to homelessness. This could be a potential life saver as well as a potential cost saver.

Vanderhoff: Thanks Claire, it was nice talking to you.

For more information about Foundations for Social Change’s New Leaf project, which demonstrated the power of cash-transfers to provide stability to the lives of people experiencing homelessness in Vancouver, click here.

This story was sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative (NEOSOJO), which is composed of 20-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland. Weiss is the editor and Vanderhoff is a reporter for The Tremonster. The West Park Times and The Cleveland Street Chronicle contributed to this report.