Turning back from the edge

In Peter Katsilis’ profession, true success is marked by client relationships coming to an end.

The licensed bilingual social worker at the May Dugan Center sees about six clients per day, including many who are experiencing homelessness in the greater Cleveland area. Others might be looking for a job or escaping a tragic situation. Katsilis has helped many achieve their goal for a better life since he started working for the Ohio City non-profit three years ago, but like many area health and human service workers, he can’t settle on any one choice as the best success story.

“One individual went from being a St. Herman House resident to a job foreman there in a year,” he says. “That was one of the bigger turnarounds that I’ve seen.”

Another resulted in Katsilis finding a new shelter for a client who immediately wanted to go to New York to escape the abuse of her niece.

“She was scared to go back to the [Cleveland area] shelter she was at when she met me,” he says. “To be able to find her a safe place and arrange for a bed in New York – I never thought I’d be able to do it under that pressure. I was proud of that.”

Organizations can provide numbers and brochures to back up the good work they do, but few things are more impactful than reflections straight from the client. And while those in crisis face untold challenges, they don't often share the stories of how they overcome them.

Fresh Water contributor Brandon Baker, however, sought out those compelling success stories from May Dugan Center and Lutheran Metropolitan Ministries clients. Their tales will give readers pause.

'I was the guy hanging out in front of the store.'

Kelly Reinhold grew up on the near West Side, but he never knew a thing about the May Dugan Center until he decided he needed it.

“I started drinking before I reached double digits,” Reinhold says during a break from a Monday evening GED course at the May Dugan Center. “I was the guy hanging out in front of the store. Recovery? I used to think it was a death sentence.”

Reinhold says he lived several years with a mental and physical obsession with drugs and alcohol that led to “panhandling and dumpster diving.” He eventually went to YMCA of Greater Cleveland’s Y-Haven transitional housing facility and achieved five years of sobriety, beginning in 2009. However, he openly refers to that period as “nothing,” and not because he relapsed in late 2014.

“I was just stagnant,” Reinhold said. “All I did was work, I didn’t do anything else.”

He continued living an isolated life, eventually finding his way back to a lifestyle of addiction and homelessness.

“I was spiritually, emotionally, financially bankrupt,” he says.

He finally decided to return Y-Haven last year, determined to do things differently this time. Part of that included being brutally honest with himself about the need for an education and a meaningful career.

He discovered the May Dugan Center simply by stumbling upon a flier for its Education and Resource Center (ERC) as he escorted a recovery program peer who was unfamiliar with the Ohio City neighborhood. Reinhold was also enrolled in the program, which is part of his return stay to Y-Haven. The flier evoked something in him.

“I’m 47 and I don’t have my GED? There’s something wrong with that,” he says. “I don’t want to be 50 years old doing meaningless work, making meaningless wages – the vicious cycle.”

Reinhold came to May Dugan’s ERC last winter filled with disdain for traditional education. Lead ERC teacher Brenda Williams says that’s common; many clients arrive with backgrounds of abuse, assault and more. That’s why she and other teachers work with ERC Coordinator Sue Marasco, Ph. D. to maintain a trauma-informed environment that is physically and emotionally safe.

The ERC offers three morning and two evening courses each week. Clients range in age from 17 to over 70, Williams says.

Reinhold has completed three of the four tests needed to get his GED. He has also been sober for seven months. He previously preferred physical labor, but time spent around the Center has him thinking about going back to school for a degree in social work so that he can one day help people who have traveled a path similar to his own.

He’s certain he wouldn’t feel that way if he hadn’t seen the May Dugan Center flier that one night.

“This is a gem in the middle of poverty,” he says. “What they do for the community is fabulous.”

‘My past doesn’t dictate my future’

Tomeka Ewing had grown tired by 2008, and told as much to the case managers and employees of Lutheran Metropolitan Ministries’ Community Re-Entry program, who supported her through all of her setbacks.

“I ain’t gettin’ high no more,” Ewing recalls telling Re-Entry staff at the time, adding that the urge to use had left her. It was a moment long in coming.

Ewing had used crack cocaine for about 25 years by then and been in and out of jail for a litany of charges, ranging from theft to domestic violence. She first learned about the Re-Entry program while she was in transitional housing and pregnant with her first daughter, now 25. Ewing wanted to get clean with a baby on the way.

Tomeka Ewing

Tomeka Ewing

Ewing went on to give birth and move into her own place while attending weekly group sessions with the Women’s Re-Entry Network, which is part of the Community Re-Entry program.

Before her recovery began in 2008 when Ewing was still on that difficult road, her “guardian angels,” including Cleveland attorney and former Community Re-Entry case manager Melanie GiaMaria, came to visit her in county jail or listen to her fears during a custody battle. She says that attention was critical to her eventual sobriety because others lacked that sort of patience and understanding.

“They loved me and taught me how to love myself and to advocate for myself,” she says. “My past doesn’t dictate my future. Yes, I have a past, but I’m not that person anymore.”

Today, Ewing is preparing for classes that will earn her a Master of Social Work degree at Cleveland State University. She’s also a group and individual counselor at Community Assessment & Treatment Services in Cleveland, helping others rehabilitate from drug use like she did eight years ago.

“Recovery is doable, but it starts with you and it ends with you,” Ewing says. “If we’re not willing to go the extra mile, we can’t blame anybody but ourselves. We’ve got to face obstacles and barriers.”

‘I want to work, I want a job.’

Repeated rejection filled Eladio Munoz’s first two years back in Cleveland after he spent three months visiting his mother in Puerto Rico.

He willingly left a job as a machinist after a year and a half while renting a room at a friend’s house. His plan was to reboot, visit family and perform tasks like painting his mother’s home before returning to the Midwest to find another job.

Instead, Munoz returned to a life of constant flux and barely getting by on food stamps. He wound up at the St. Herman House, where he was introduced to Katsilis and the May Dugan Center with goals of gaining employment and his own residence.

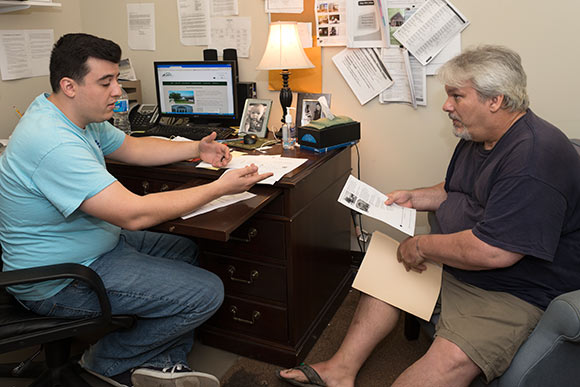

May Dugan Community Education Classes

May Dugan Community Education Classes

He stayed at the shelter for about a year and found a job under the guidance of May Dugan’s Counseling and Community Services Department. However, he received a double dose of rejection when that business closed and his Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Association application wasn’t approved.

“People tried to tell me to apply for disability,” Munoz says with a hint of anger, “but I’m not disabled. I want to work, I want a job.”

When he wasn’t visiting with Katsilis, Munoz could be found at the nearest library scouring online job postings and print classified sections. He was emboldened by a varied work history that included technician jobs in hospitals, maintenance and security guard shifts.

It paid off, as Munoz now works at a restaurant in Rocky River and lives in an apartment on West 25th Street. His next goal is to get a car.

“You can’t stay still, you’ve got to keep a positive mind,” he says. “It was a process, and it was time consuming, but I hung in there.

“May Dugan, they helped me a lot. I did what I had to do to better myself.”

This story is one of a Fresh Water series supported in part by the May Dugan Center.

.jpg)