Boosting the dream: Cuyahoga Arts & Culture grants set these two artists on an upward trajectory

Filmmaker Cigdem Slankard makes films that reveal the immigrant stories in her adopted hometown of Cleveland. Her films have a positive outlook on the city’s ability to be a portal of opportunities for immigrants landing here in search of a better life.

For dancer LaChanee Hipps, dance opened up opportunity, including a spot in the dance corps of East Cleveland’s vaunted Shaw High School Marching Band, at Alabama State University, a HBCU (Historically Black College and University), and as a member of the Cavaliers’ PowerHouse Dance Team. Hipps own experiences inspired her to start Buck Out Cleveland, an organization that she founded in 2016 to give young Black women the tools they need pursue dance careers.

Over the past four years, both Slankard and Hipps received Cuyahoga Arts & Culture (CAC) funding to pursue their work. In 2019 Slankard received a $5,000 SPACES Urgent Art Fund grant through CAC’s partnership in the fund. Hipps in 2019 received a $5,000 Karamu House Room in House Residency, which is funded through CAC; and then Buck Out received a $5,000 Project Support grant in 2021 and a $7,640 Project Support grant in 2022.

The funding helped the two artists boost their careers, develop other young aspiring artists, and give back to others in Northeast Ohio.

Note: The deadline for CAC 2023 Project Support Grant applications is May 31. Click here to start the process. SPACES Urgent Art Fund is accepting applications until May 27.

Both women express their gratitude for CAC support because it allows them to reach people and channel their experiences as an immigrant, as women of color, and as artists. The CAC grants helped Slankard and Hipps to thrive in their respective arts over the past three years.

“Artists tell us that a grant from a CAC-funded organizations like Karamu, SPACES. and Julia de Burgos can be a difference maker in their careers—helping them launch a project or attract new money,” says CAC executive director Jill Paulsen. “LaChanee and Cigdem are two fabulous people who remind us that when artists get flexible funding, access to physical space, and professional development they can—and deserve to—go far.”

Here is a look at how CAC helped boost Hipps’ and Slankard creative careers.

Cigdem SlankardThrough the camera lens

Cigdem SlankardThrough the camera lens

Slankard was born and raised in Turkey, but as fate would have it, she followed a trail from earning a degree in translation and interpretation in Istanbul to attending graduate school in filmmaking in upstate New York and at Ohio University, to landing a job in Cleveland.

Slankard says she had no preconceived notions about Cleveland when she arrived, and that wide open lens is evident in her films, which are mostly about Cleveland as a place of opportunity, despite its own ability to see it.

“For the past 10 years, the films I have made are refugee-focused stories about home, housing and what does it mean to be from somewhere,” says Slankard, interim director and assistant professor, at Cleveland State University School of Film & Media Arts. “This was indeed a deep question for me both from my upbringing as daughter of a refugee family and also as an immigrant.”

In her latest film, “Breaking Bread,” Slankard enters the homes of refugee families as they prepare and sit down to a meal—sometimes on a rug, sometimes on a banquette of pillows, or in a cramped Cleveland apartment with modest furnishings.

Slankard uses Virtual Reality (VR) to enable viewers to scroll 360-degree views of her subjects as they slice and dice, talk to family members handling babies, or share space with kids playing video games. The idea, she says, is to generate empathy and a sense of commonality with something as familiar as making a family meal or trying to get young ones to log off video screens.

“Breaking Bread” begins with mundane daily check ins on school and work, but the more the camera lingers, the more we see the appreciation for the relative safety and opportunity in the U.S. That appreciation is mixed with the frustration of not being able to convince landlords to invest in fixing things, in communications gaps, or with the unsettled feeling created in childhood from constantly moving.

“I am from Ohio,” Slankard says. “I have never lived somewhere this long. This is the most settled I’ve been. It’s where I built my home and raise my children.”

But Slankard’ s film shows the worries that often accompany being a refugee in a new land. “As I was making ‘Breaking Bread,’ I would drive to my comfortable house in Rocky River and I would think about what people had told me, like [Congolese refugee] Emmanuel who said, ‘I prayed that God gives me English,’” Slankard explains. “He is happy for the most part because he can sleep at night knowing his children are safe. But he prayed that he would be able to learn to communicate.”

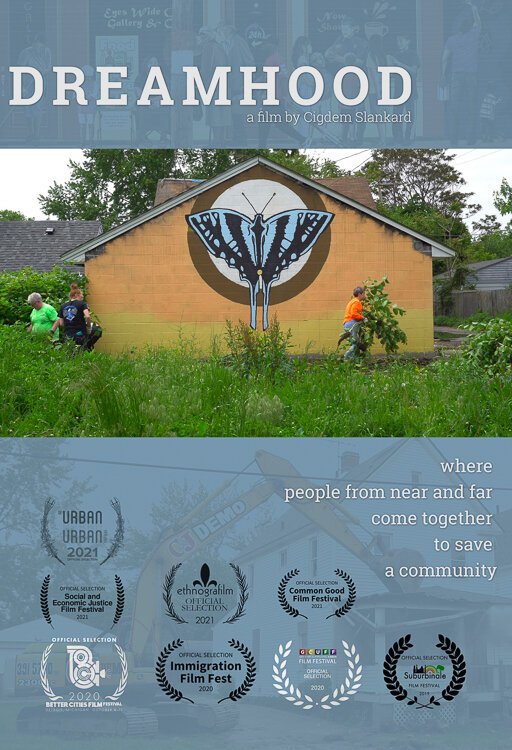

Slankard sees her films as a celebration of how diverse Cleveland is becoming—as evidenced in her 2019 documentary “Dreamhood” about life in Cleveland’s near west side community International Village. There are scenes of a bustling elementary school, where multiple languages are spoken, of houses being fixed up, and of murals celebrating multi-culturalism in a neighborhood that was rocked by the 2008 foreclosure crisis.

“Turkey is so crowded, there’s no room,” says Slankard. “In Cleveland, the prime real estate [is vacant]. You wonder, ‘how come there’s no business here?’ Cities are [about] changing demographics. We also need people here to work.”

As an immigrant herself, Slankard sees Cleveland as a place for potential opportunity and a diverse community.

“It’s rather serendipitous how people end up in Cleveland as refugees,” she says. “They don’t have a choice. If they find they can afford to stay, they stay. I think [my] work does make a case for having a diverse group of people around us. It makes for a richer life.”

Weaving a tapestry through dance

Weaving a tapestry through dance

As a professional dancer who achieved her dreams that others had not even considered, Hipps says she sees herself creating a rich tapestry of young talent by teaching young Black women how to dance at Buck Out Cleveland’s MidTown studio space.

“Our mission is to bridge the gap between Northeast Ohio youth through dance and exposing them to potential dance careers,” she says. “I was one of the first [from Shaw High School] to have a successful college dance career.”

Making the leap from the well-respected high school’s marching band to a college band wasn’t without its trials and tribulations. Hipps didn’t earn a spot in the bands right away—she had to take classes and build skill while dancing with professionals in various dance forms like jazz and ballet before earning a spot as a Mighty Marching Hornet with the marching band at Alabama State.

Hipps credits her college dance sorority, Tau Beta Sigma, for “activating the service person in me.”

After she graduated college with a B.S. in biology, Hipps realized she had a lot to offer the next wave of young Black women like herself. So, she organized pop-up workshops and offered private lessons while also balancing duties as a program manager at the arts education-oriented Rainey Institute. That experience became the basis for Hipps’ studio and the founding of Buck Out Cleveland in 2019.

Small and looking for a sustaining source of income, Buck Out Cleveland has cemented relationships with the Cleveland Metropolitan School District and alumni groups at several HBCUs across the country.

“I was sought after for these skills,’ Hipps says. “I found myself evolving into someone who cares about these students’ whole being. I feel like I’m navigating my purpose to be able to provide a safe space for these dancers to not only grow and tone their bodies, but also emotionally and socially connect.”

Hipps says she sees her charge as building the pipeline from high school to college marching band—and eventually to a professional career in dance. She offers workshops and mock auditions and prepares her students (who can be as young as nine years old) mentally for the grueling task of disciplining their bodies and minds. She tells her older students that she expects them to come back one day and contribute to that growth in others.

“I say, ‘this is your time to teach and show us what you’ve been learning,’” she says. “They are Buck Out Cleveland. They are the future.”

Hipps makes a convincing case based on the strength of her own experience as a professional. As she nears the end of her 20s and starts to focus more on teaching, Hipps reflects on the impact mentors and coaches make—and that impact is just as important as the accolades received from being on stage.

“From my coaches and teachers, I absorbed the discipline or using [teaching as a] platform,” she says. “Even now. I’m looking for ways to grow. My biggest mentors are my parents. It’s not [just]about going to school but being able to have someone to lean on.”