Living a childhood dream: East Cleveland woman to convert Rockefeller-Rudd house into museum

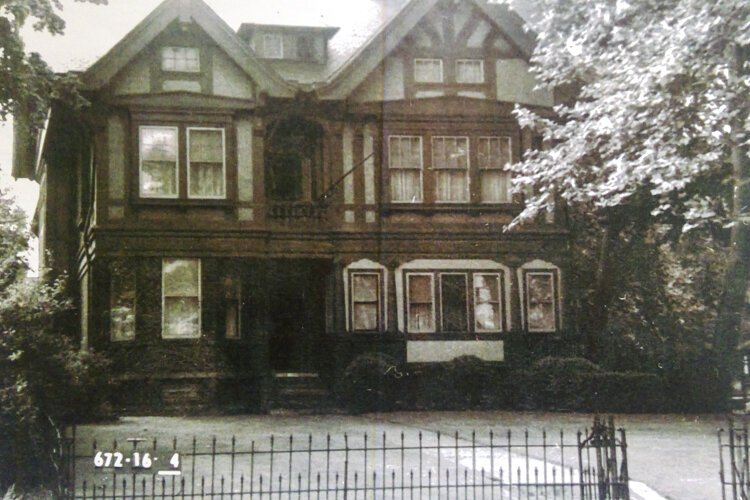

Sheila Sharpley has had her eye on the house at 13204 Euclid Ave. in East Cleveland. Even as a child, she recalls dreaming of one day owning the seven-bedroom, five-bathroom Tudor Colonial home that once belonged to Mary Ann Rockefeller Rudd (sister of John D. Rockefeller) and her husband, William Culver Rudd.

“It was just one of those houses I used to see all the doggone time,” says Sharpley. “I should have been a real estate agent instead of an insurance agent.”

The exterior of the Rudd-Rockefeller house on Euclid Avenue today.The historic house even caught FreshWater Cleveland’s attention when it wrote about The 8 Most Interesting Homes in Cleveland back in 2018. Now Sharpley is the proud owner of the Rudd-Rockefeller home and is in the process of repairing and restoring it to open a museum.

The exterior of the Rudd-Rockefeller house on Euclid Avenue today.The historic house even caught FreshWater Cleveland’s attention when it wrote about The 8 Most Interesting Homes in Cleveland back in 2018. Now Sharpley is the proud owner of the Rudd-Rockefeller home and is in the process of repairing and restoring it to open a museum.

In 2012, Sharpley almost missed her chance at the Rudd-Rockefeller mansion. A friend was looking for a house, and Sharpley on a whim decided to find out if her dream house was for sale.

She discovered that then-owner Marian Pledger had sold it a week before her inquiry.

“I was devastated,” Sharpley says. “I called my husband, Michael, and he said, ‘What is meant for you is meant for you. It just wasn’t for you.’ Seven days later, the agent called me and said the woman who bought the home had lost her job and moved to Boston. She asked if I wanted to buy the house.”

Sharpley jumped at the chance and bought the condemned 7,900-square-foot mansion for $32,000. “I got it for a song,” she says, “I got it for nothing.”

After she bought the house, Sharpley turned to Angelina Bair, a librarian, historic property expert, and founder of Bair Consulting, to research and unveil the history behind the Rockefeller-Rudd mansion.

The house was built in 1901 by the Windermere Realty and sold to Annabell Wilson Nobles and Newman Nobles. In 1905, the house was sold to the Rudds. William was president of Chandler and Rudd grocery and operated Rudd’s Pharmacy, reportedly out of the house at one time.

William died in 1915, and Mary Ann left it to her two surviving children,

William died in 1915, and Mary Ann left it to her two surviving children,

Frank then sold it to the Children’s Guild in 1966. Additions and alterations were made over the past 118 years, including a sordid history of additional land parcels purchased, a change of house number (from 13176 Euclid to 13204 Euclid), and the conversion of a two-car garage to three-car garage.

It changed ownership a few more times before Sharpley was able to buy the house she had always coveted.

However, by the time she took possession, the mansion was in bad shape. Vandals had invaded, stealing all the copper plumbing and ripping out fixtures. (Some vandals had even attempted to drag radiators down the two stairways and the boiler from the basement but gave up when they realized they were too heavy to carry down the street.)

“They knew we were not there, and they stole every piece of plumbing,” Sharpley says, as she keeps an optimistic outlook. “But the plumber said, ‘I know where the pipes are and I don’t have to remove it.”

A neighbor stole the wooden planking boards outside that were once used to tie horses, and Sharpley says evidence of squatters living in the home, like children’s toys and garbage, was obvious.

Additionally, Pledger moved into an assisted living facility and left most of her belongings behind. “When she left the house, it was full of furniture, pictures, it was just full of a whole bunch of stuff we had to get rid of,” Sharpley says. “She just took what she wanted to take. She took the bare-bones minimum.”

Despite the mess, Sharpley only saw the beauty and the history of the house and has been slowly working toward restoring it and turning it into a museum, of sorts, of 1901 living. “I want it to be preserved forever,” she says.

And the hardwood floors, crown molding and original wood trim are all intact, and the house is otherwise in good shape, Sharpley says.

While Sharpley knows a lot of work has to be done to the home—a new roof, a new heating and cooling system, and all new plumbing—as well as alterations reversed from when it was a group home (in addition to the Children’s Guild, other owners included the Cuyahoga County Boys Home and Cleveland Crossroads for Youth). For instance, Sharpley says one bathroom has three shower stalls, seven closets, and two toilets in it.

The third floor originally served as a ballroom—like many area home designs of that era—but Sharpley says it had been divided into small rooms and a bathroom. “I want to put it back to the way it was and make it a ballroom again,” she says.

Another project includes turning the basement into a professional kitchen so she can serve food to tour groups and school children who might come through on educational tours. “I would like for schools to come through and learn about early times, learn about East Cleveland,” she says. “I want them to learn about how clothes were washed [in the early 1900s], how you made butter, how did you light a stove.”

But for the most part, Sharpley wants to take the main parts of the house back to the early 20th century and make the whole house a museum. She says she would like to make one of the five bathrooms reflect a typical bathroom of the era.

Vandals tried but failed to drag radiators down the stairs.She says many of the light fixtures in the library are the original fixtures, although the living room and dining room have no lights currently. “I want to make it like you walked back into the 1901 time period,” she says.

Vandals tried but failed to drag radiators down the stairs.She says many of the light fixtures in the library are the original fixtures, although the living room and dining room have no lights currently. “I want to make it like you walked back into the 1901 time period,” she says.

Sharpley has already begun collecting pieces that will fit the historic theme. She secured an 1896 washer for $60 from Facebook Marketplace, as well as a 15-pound glass and marble pen set, found a pair of 1895 scissors and a piece of a wedding dress owned by the same person, and is collecting photographs from the early 1900s.

“And I’m eyeballing an 1890 wood icebox,” she says. “But I need a new refrigerator and I need a real one.” Sharpley says she considered buying an 1890 pipe organ for two months, but it sold before she could make an offer.

Sharpley says she is taking her time to get everything fixed and every detail correct. She estimates that the repair work will cost between $100,000 and $150,000 but will not estimate the cost of the antiques she is collecting.

“When you walk into the house, I want it to reflect that time period from 1901 to 1921,” she says. “From the curtains to the knickknacks, and I want that kitchen to be from 1901.”

Cleveland Storyteller Dan Ruminski has been helping Sharpley piece together the history of the Rudd-Rockefeller home, and she says he has offered to put together a fundraiser for the project.

“I know it’s going to take me a minute to get everything the way I want it, but that’s the way I really want it,” she says.

Despite the work ahead of her, Sharpely is thrilled that she finally owns the house she’s been keeping her eye on since childhood. “This is my dream,” she says. “It’s my dream home. It’s my legacy. I want to pass it on to my son so he can pass it on to his children. If I didn’t think I could do this, then I wouldn’t.”

And Michael’s words came true. “I knew this would eventually be mine,” she says. “And now it is.”