Cleveland insider: Sarah Allison Steffee Center for Zoological Medicine

While visitors enjoy the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo’s exhibits such as the new Rosebrough Tiger Passage, Wallaby Walkabout and the exotic RainForest, few realize that the Zoo is also home to the Sarah Allison Steffee (SAS) Center for Zoological Medicine, wherein the facility's 3,000 animals and specimens receive the very best care. In addition to veterinarian services, the SAS Center also focuses on science, conservation, education and research.

For example, graduate research assistant Austin Leeds studies oxytocin – a hormone that plays a role in social bonding and sexual reproduction – as a measure of bonding between social groups of gorillas, while Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) graduate student Janny Evanhuis compares giraffe movement in zoos to that of those in the wild where a poorly understood skin disease is affecting many of the populations.

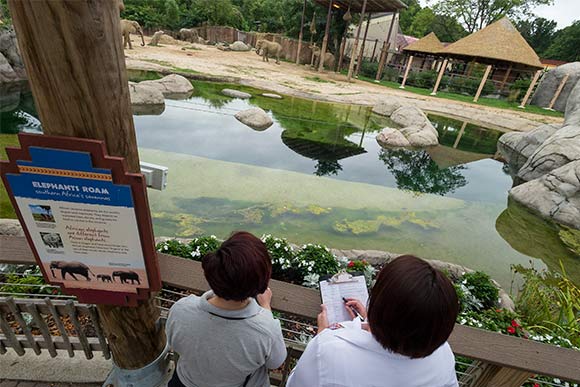

Graduate research associates Laura Bernstein Kurtycz and Bonnie Baird observing the elephants

Graduate research associates Laura Bernstein Kurtycz and Bonnie Baird observing the elephants

Graduate research associate Bonnie Baird measures how adding enrichment devices such as elevated feeders and working with social structure has improved social behavior and health amid the Zoo’s African elephant herd. All the while, the Zoo’s veterinary epidemiologist researches the impact of diet on cheetahs by comparing infrequent large meals to more frequent small meals. (In the wild, cheetahs only eat every few days.)

The Zoo’s formal relationship with CWRU includes four doctoral student positions. The students take classes at CWRU to receive their doctoral degree in biology while conducting research at the Zoo, which also hosts students from Baldwin Wallace, Colorado State University, The Ohio State University, and the Tri-C veterinary technician school. Some members of the Zoo staff also maintain adjunct teaching positions at each of these universities. The Zoo’s education department has a formal relationship with Miami University master’s program in advanced inquiry as well.

Top Priority: Animal Health and Wellness

“We typically have four full-time PhD students who all have a lab component to their projects,” former Cleveland Metroparks Zoo associate research curator Mandi Wilder Schook explained. “In addition, our veterinary resident works in the lab, as do several master’s students from local universities. They learn endocrine assay techniques to monitor various hormones in the species they are studying," she said of the qualitative and quantitative evaluations students perform on various substances sampled from animals.

"We also have long-time dedicated volunteers that come in weekly to help us process samples by weighing out fecal samples and making various sample dilutions. Students do all aspects of running the hormone tests, including collecting and drying samples, weighing them out, diluting them, running the assays and analyzing the data. On the veterinary side of things, we have a conservation medicine resident, often train veterinary technicians while they are in school for four to eight weeks at a time, and have visiting veterinary school preceptors.”

Educational research is among the many activities unfolding within the SAS's 24,000-square-foot building, which is divided into four areas. They include a quarantine area wherein new animals spend 30 days undergoing medical evaluations and an animal hospital with separate treatment areas for small and large animals, a radiology lab, clinical labs, and a pharmacy. The conservation and science wing houses offices, laboratories, a library and a new endocrinology laboratory. Lastly, the Reinberger Learning Lab is an adjoining education pavilion where Zoo visitors learn about veterinary care via displays and views to surgical suites where veterinarians perform treatment procedures.

“Animal health and wellness has always been the Zoo’s primary concern, so the SAS Center was designed to deliver not only the best care possible for the Zoo’s animals but to enhance that work through research, education and conservation capabilities,” Schook explained. “The facility was designed to support technological advances in veterinary care with state-of-the-art equipment.

“The SAS Center brings the Zoo’s conservation and science department together with veterinary medicine staff to encourage collaborations that can have the greatest impact on animal health. It also engages Zoo visitors in animal life cycles and care with memorable exhibitry supported by on-site educators through the Reinberger Learning Lab. The SAS Center reinforces the Zoo's role as a leading institution in scientific animal management.”

Currently, the Zoo has two full time veterinarians, a veterinary epidemiologist who studies population health, and four veterinary technicians. Their preventative health program attempts to increase animals’ day-to-day health and comfort. Staff veterinarians use cutting-edge equipment (such as ultrasound and a CT scanner) to diagnose health concerns.

“In addition, our epidemiologist looks at health on a species level to provide optimum diets, lighting and other aspects of day-to-day life to ensure good health and welfare.” Schook said. “Many of our animals are trained for voluntary ultrasound or blood collection, which allows us to be better able to monitor health and diagnose any issues.”

SAS Center veternarians perform an annual check up on Metroparks Ranger K-9 officer Logan

SAS Center veternarians perform an annual check up on Metroparks Ranger K-9 officer Logan

Members of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums – with which the Cleveland Zoo is accredited through 2019, said Schook, share information and work together to find ways to best care for various species. Zoo staff also publishes their research findings in nationally recognized peer-reviewed journals. Lately, they have been focusing on animal diets.

“We have looked at the standard commercial animal diets that often come in the form of a grain or biscuit (think of it like cereal that humans eat that is fortified with vitamins and minerals), and then enhanced or completely changed the diet by adding more greens or natural forage for our herbivores, or adding more meat for our carnivores,” she said. “In many species, making these changes has resulted in improved health and behavior.”

An Extended Obligation

A significant amount of time, effort, and formal research goes into providing science-based care for the Zoo’s animals. Employees also perform research related to both local species and those on other continents. Finally, the Zoo often provides information and resources for local scientists.

“Whenever an animal in our collection dies, the veterinarians complete a full necropsy to determine cause of death and to learn as much as possible regarding the health of the animal,” the Zoo's veterinary epidemiologist Dr. Pam Dennis explained. “Tissue samples are taken from all the organ systems and are examined by pathologists to determine if there are signs of disease. Additionally – to learn as much as we can about the individual animal as well as the species – tissues are shared with other scientists seeking to answer specific questions.

“Some of the questions being asked by scientists are [regarding] general anatomy or physiology, others are focused on evolutionary processes, while others are asking more specific health related questions. We have also provided samples to the US Fish and Wildlife Service to aid in identifying endangered species in the illegal wildlife trade. All the information gained from this additional work adds to our knowledge and understanding of the animals in our care.”

Mary Ann Raghanti, associate professor and interim chair of the department of anthropology at Kent State University, began working with the Zoo in 2003 as a graduate student researching the physiological correlates of primate behavior. Since then, she has received many brains from the zoo from a large variety of animals, from turtles to hippos.

“We routinely use these specimens to learn more about the species themselves,” she said. “Each organism is exquisitely adapted to be very successful as that organism. That requires specializations in the organization and structure of the brain. This information also contributes to and improves our understanding of how brains function. Finally, this information helps to identify why we, as humans, are uniquely susceptible to neurodegenerative processes that are associated with decreased cognitive function, such as Alzheimer’s disease.”

She added that although we are not the only species with cognitive decline associated with neurodegeneration, we do appear to be unique regarding several diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease.

“By identifying how our brains differ from those of other species, we identify what neuroanatomical features make us human. Those same features that set us apart may make us vulnerable to disease processes,” she said.

From MRI imaging whole brains to using molecular techniques to examine genetic differences, sectioning and staining the brains to measure cell types, neurotransmitters, and other components, the samples provide information otherwise unobtainable.

“The value of the Zoo samples cannot be overstated,” she added. “I think that we are obligated to provide the best quality of life to the animals housed in zoos, and we have an obligation that extends after they die to learn as much as we can from each individual.”

Mandi Wilder Schook was an associate research curator with the Cleveland Metropark Zoo for more than six years. Just after being interviewed for this article, she accepted a position with Disney's Animal Kingdom.

The Cleveland Metroparks is a member of Fresh Water's underwriting network.