Filling the silence: CLE Silent Film Festival will celebrate the music of J. S. Zamecnik

The first-ever Cleveland Silent Film Festival and Colloquium: Music That Once Filled the Silence will this month celebrate the emergence of music paired with films at venues around Northeast Ohio.

The festival kicks off Sunday, Feb. 13 and runs through Sunday, Feb. 20. The weeklong festival is presented by Cleveland Arts Prize, the Cleveland Institute of Art Cinematheque, Cleveland Institute of Music, Case Western Reserve University, and the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, and features films and their associated concerts, discussions, and a workshop.

The festival kicks off Sunday, Feb. 13 and runs through Sunday, Feb. 20. The weeklong festival is presented by Cleveland Arts Prize, the Cleveland Institute of Art Cinematheque, Cleveland Institute of Music, Case Western Reserve University, and the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, and features films and their associated concerts, discussions, and a workshop.

A silent film festival has been a persistent dream for Emily Laurance, visiting associate professor of music history at Oberlin Conservatory and the festival’s chief organizer.

“I've long wanted to build something like this in Cleveland, a city whose history was shaped by the same era that produced these cinematic classics,” she says. “It gives [music students and working musicians] opportunities to engage with past art in ways that also bring out their own creativity, and to think about the power and potential range of meaning of purely instrumental music.”

At the center of the Silent Film Festival is a name long forgotten.

American composer, conductor, and native Clevelander John Stepan Zamecnik (1872–1953) was a pioneer in composing music to accompany then-silent films. He deserves to be remembered—and celebrated—as one of the most important figures in the silent film era and a pioneer in the evolution of film soundtracks.

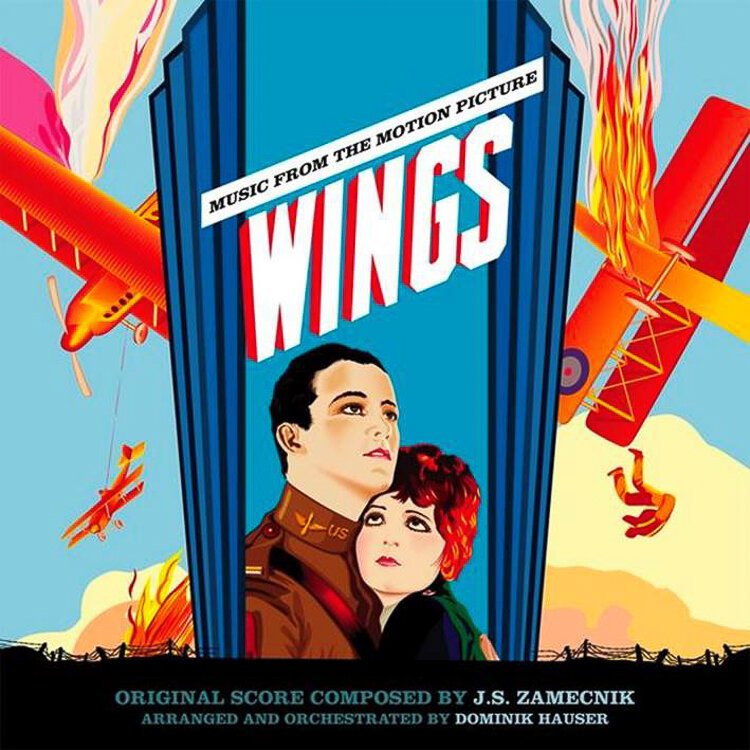

Zamecnik (pronounced ZAM-ish-nick) would go on to score some 40 films, including the 1927 film “Wings,” the first movie ever to be given an Academy Award for best picture.

If you haven’t seen this classic, you’ll want to catch it when it’s shown on Friday, Feb. 18 at the Cleveland Institute of Art Cinematheque in a gloriously restored version that not only preserves the original color tinting, but also Zamecnik’s original musical score.

Cinematheque director John Ewing likes to describe “Wings” as the story of “two American flyboys who love the same woman, each other, and airplanes (not necessarily in that order). The thrilling aerial sequences and battle scenes are authentic as well as spectacular.”

The Cinematheque is one of five area institutions that will be participating in this week-long celebration of one of several of Cleveland’s forgotten Past Masters whose rediscovery—and celebration—identified last fall by Cleveland Arts Prize as derverving redisovery..

The festival begins on Sunday, Feb. 13 at 3 p.m. at the Hermit Club, where Zamecnik once wrote music for and led a small orchestra in a series of zany musical revues so popular they had to be staged across the street at the Euclid Avenue Opera House.

The Feb. 13 performance will feature members of the Cleveland Orchestra, led by Isabel Trautwein, performing the chamber music Zamecnik wrote during his studies with the great Czech composer Antonín Dvořák in Prague.

The program will include a masterwork from Dvořák’s brief sojourn in America that gave us his majestic New World Symphony, as well as colorful examples of the music Zamecnik wrote to accompany specific kinds of scenes in silent films. Tickets are $15 to $100 and can be purchased in advance.

It was the rapid rise in the 1910s of the newest rage—silent movies—that was to open a whole new career path for Zamecnik—one his famed teacher Dvořák, who died in 1904—could never have foreseen.

It was the rapid rise in the 1910s of the newest rage—silent movies—that was to open a whole new career path for Zamecnik—one his famed teacher Dvořák, who died in 1904—could never have foreseen.

Zamecnik gave his compositions titles such as “The Awakening,” “The Furious Mob,” “The Evil Plotter,” and “Remorse.” Word spread, and soon movie theaters all over the United States were writing his publisher, Cleveland-based Sam Fox Publishing, begging for this music.

Audiences from New York to Los Angeles, sitting in the dark, were riveted to the action on the screen as Zamecnik’s imaginatively conceived and richly scored music set the mood. It was only a matter of time before Hollywood came knocking on his door.

Zamecnik’s music breathed life and color into every film he was involved with—from sea battles between the U.S. Navy and the Barbary Pirates in the 11-reel 1926 silent epic “Old Ironsides,” to the poignant humor of the 1928 “Abie’s Irish Rose,” an eagerly anticipated adaptation of the longest running play in the history of the American stage about a marriage between a Catholic and a Jew.

Zamecnik was to prove equally adept at tackling more serious subjects in such landmark films as the 1929 “Betrayal,” the final silent appearance of the great German actor Emil Jannings. Zamecnik also scored the 1933 Spencer Tracy film The Power and the Glory.

Zamecnik’s music was played in thousands of movie theaters virtually every night for 15 years. The opening theme of a popular circus march he composed for the 1935 film “World Events” would begin and end 20th Century Fox’s nationally distributed Movietone Newsreels for decades.

And if the music to which many Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies characters zipped about seems strangely familiar, it was because they were often Zamecnik’s recycled silent movie cues.

Zamecnik stuck with his craft until his retirement in 1938, continuing to provide music for fighting Marines, the adventures of Rin Tin Jr., and Charlie Chan in Egypt. But his heart, he admitted to his sons, would always belong to the Silent Era.

Finally getting to hear Garbo talk had come at a steep price: tinny, low fidelity recorded music that struggled to be heard above the dialogue and the now endless sound effects. In the Age of the Silents, the glorious sounds of rich orchestral music performed live by musicians sitting a few feet away had given audiences an almost visceral thrill, enriching and deepening what was unfolding on the screen: the sweetness of first love, the rush of bravery, the sting of betrayal, the rediscovery of hope.

Finally getting to hear Garbo talk had come at a steep price: tinny, low fidelity recorded music that struggled to be heard above the dialogue and the now endless sound effects. In the Age of the Silents, the glorious sounds of rich orchestral music performed live by musicians sitting a few feet away had given audiences an almost visceral thrill, enriching and deepening what was unfolding on the screen: the sweetness of first love, the rush of bravery, the sting of betrayal, the rediscovery of hope.

For one week in February, Clevelanders will be able to know again what Jazz Age audiences experienced when the lights dimmed, and the camera’s eye opened on another world.

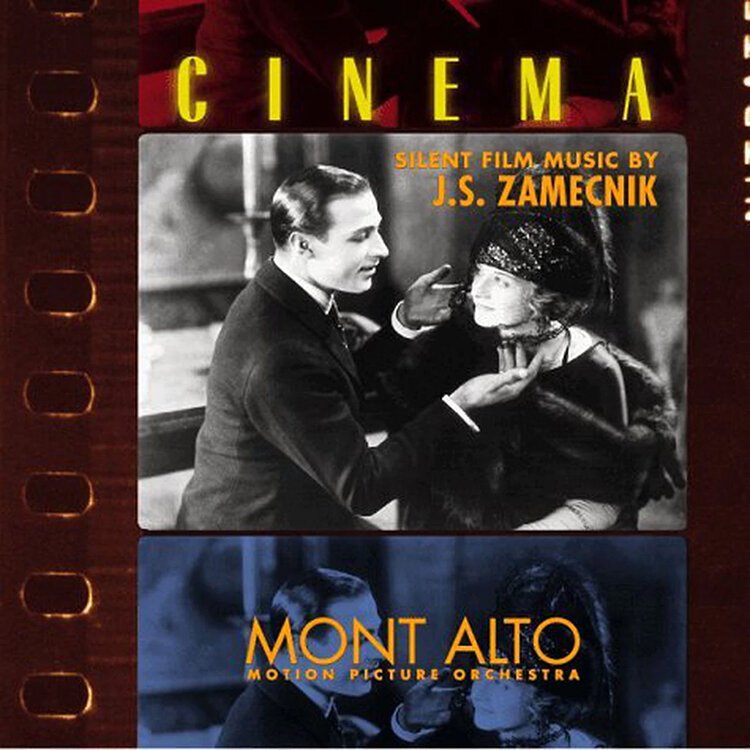

Four of the films for which Zamecnik produced full scores will be shown during the Cleveland Silent Film Festival—three of them accompanied live by the renowned Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, which has won national praise for its mastery of the art of performing this music.

Oberlin’s restored 1913 Apollo Theater will show “Steamboat Bill, Jr.,” directed by and starring the great physical comic genius Buster Keaton. Awaiting the visit from a son he hasn’t seen in years, a beleaguered excursion boat owner expects a husky scrapper like himself. Jr., played by Keaton, shows up with a pencil-thin mustache and beret, strumming a ukulele.

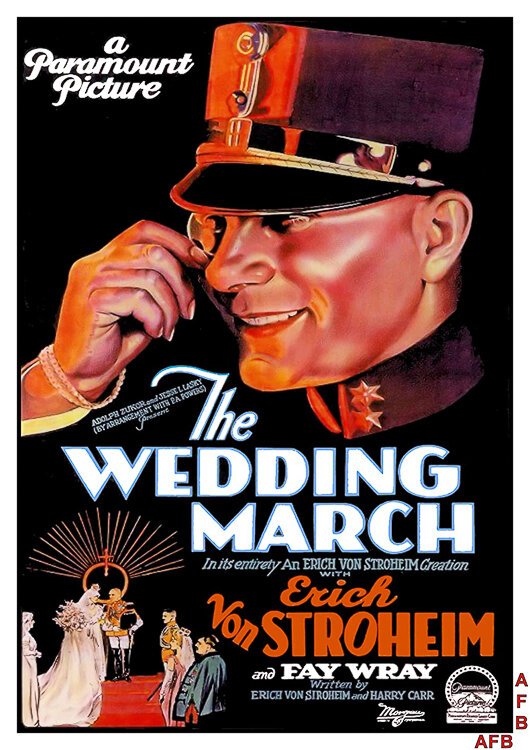

The Cinematheque will show Eric von Stroheim’s lavish silent 1928 melodrama “The Wedding March” on Saturday, Feb. 19 at 7:30 p.m. On Sunday, Feb. 20 at 3:30 p.m. Cinematheque will close Cleveland Silent Film Festival with a showing of the 1927 film “Sunrise”—the deeply affecting story of love lost and found, which many consider the greatest film of the Silent Era.

Under the guidance of Mont Alto Orchestra director Rodney Sauer, Oberlin Conservatory students will accompany short silent films with historic photoplay music. The performance is on Tuesday, Feb. 15 at 7:30 p.m. at the college’s Birenbaum Innovation and Performance Space and is free and open to the public.

“Cleveland is the perfect place to do a silent film festival that focuses on music,” says Oberlin’s Laurence. “Not only because it was a center of early film music publishing, but because of the number of exceptionally high-quality music students in the area.”

Case Western Reserve University will host Sauer on Friday, Feb. 18 for a free colloquium on the art of silent film scoring. “This is an emerging field of employment for professional musicians,” says Sauer.

Laurence adds, “It has been humbling and gratifying to see the excitement this project has generated, and how it's enabled so many area arts and educational institutions to work together towards a common vision, and to find new audiences to share it with, especially in a time where we all need something to bring people together and create something positive.”