Northeast Ohio agencies prepare for booming 'silver tsunami'

Area agencies prepare for booming 'silver tsunami'

After World War II, millions of U.S. military veterans left the ravages of war to return home and create life. They married and produced babies in massive numbers starting in 1946. By the time the baby boom ended in the mid-60s, 76 million babies had been born in the United States according to the Population Reference Bureau, which was a huge leap from the approximately 50 million that made up the previous “Silent Generation.” Today, baby boomers, between 53- and 71-years-old, have begun to retire. As they age and become less independent, they are stirring a “silver tsunami” across the United States, straining public and nonprofit agencies and pressuring the private senior-housing market.

Locally, the city of Cleveland, Cuyahoga County and nonprofits that help seniors are aware of the coming wave and are taking steps to prepare. Their top aim is to keep seniors at home since they prefer that option and because nursing homes, which are funded mostly by Medicaid, are significantly more expensive. But whether government agencies and nonprofits will have enough money and resources to handle the burgeoning senior population is unclear. Even now, some low-income homebound seniors lack consistent access to food, making them food insecure. Others are isolated and can’t find reliable transportation.

Emily Muttillo, applied research fellow at the Center for Community Solutions, a Cleveland nonpartisan think tank that studies health, social and economic issues, says senior advocates are warning that existing funds and resources are insufficient. Among those sounding the alarm is Richard Jones, director of Cuyahoga County's Senior and Adult Services.

“We need to get our heads out of the sand and realize we have a major issue on the horizon,” Jones says.

Meanwhile in the private sector, developers are building more nursing homes, assisted living communities and independent senior apartments. At least one local firm, Omni Properties, has switched its focus from offices and industrial buildings to senior housing.

“Based on overall senior population and projected growth and the senior housing units we have and the construction going on, we (senior housing developers) will not be able to keep up with demand,” says Mario Sinicariello, president of Omni Senior Living.

"A major demographic shift"

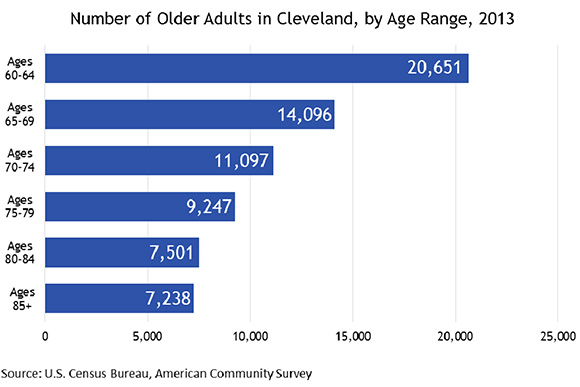

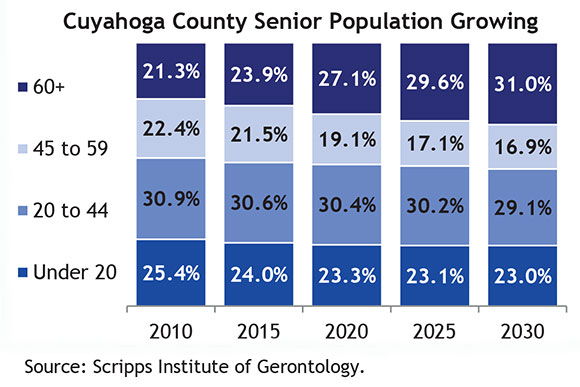

According to the Center for Community Solutions, 21.3 percent of Cuyahoga County residents were 60 and older in 2010. That number rose to 23.9 percent in 2015, and is projected to reach 27.1 percent in 2020, 29.6 percent in 2025 and 31 percent in 2030.

“2030 will be the first time there will be more older adults in the county than children,” Muttillo says. “That’s a major demographic shift.”

The larger regional picture is even more dramatic. Douglas Beach, CEO of the Western Reserve Area Agency on Aging, which provides meals, in-home care and other services for seniors in five counties, adds that in 2010, those 60 and older made up 21 percent of the population in the agency’s coverage area. The percentage is projected to nearly double to 40 percent, by 2040.

Benjamin Rose Institute on Aging

Benjamin Rose Institute on Aging

That’s a worry for government agencies like the Cuyahoga County Division of Senior and Adult Services, which since 1992 has assisted about 30,000 seniors annually. The division’s $18 million budget is funded mostly through a county health and human services levy. The division investigates reports of senor abuse and neglect; helps seniors find housing, healthcare and food programs; provides in-home health aides after a hospital stay; and financially supports municipal and nonprofit senior centers. For the most part, county services are free for seniors earning about $18,000 a year or less. For many of them, Social Security is their sole income source.

Nonprofits are doing their part. Senior Transportation Connection gives 500 rides daily to seniors and disabled citizens throughout the county. About 80 percent of program funding comes from municipalities and nonprofits that used to transport seniors themselves, says Janice Dzigiel, the organization's executive director.

Also, the Greater Cleveland Food Bank’s new three-year plan, approved in 2016, focuses on the growing senior population, says Karen Pozna, foodbank spokesperson. The foodbank supplies hot senior meals through various organizations, including the Benjamin Rose Institute on Aging, and recently launched a farmers market program that delivers fresh produce to senior apartments in Cleveland.

Still, the Western Reserve organization's Beach says Ohio ranks amid the ten worst states in the nation when it comes to senior food insecurity and is the single worst Midwestern state. Northern Ohio’s food-insecurity rate for seniors is the second highest in the state.

Jones, from the county agency's point of view, sees the senior hunger problem locally.

“I received a request for help this year from a senior center operated by the city of Euclid,” he says. “They don’t have enough money to fund their home-delivered meal program.”

Part of the problem, Muttillo adds, is that federal money for local senior services—administered through the 1965 Older Americans Act—is not keeping up with the soaring population. The amount allocated annually for each senior has fallen from about $54 in 1993 to $30 in 2014, and will continue to drop. Western Reserve has felt that pinch. Beach says the agency has served a total of 602,000 fewer meals over the last 14 years.

Jones recommends appointing a task force that consists of government officials and business leaders to study the issue regionally.

“Our community needs to recognize that older persons helped build a strong city and county,” he says. “They worked hard all their lives. There is a moral and ethical imperative that we make sure they live their lives with dignity and purpose, and feel valued as persons who have made contributions over their lifetimes.”

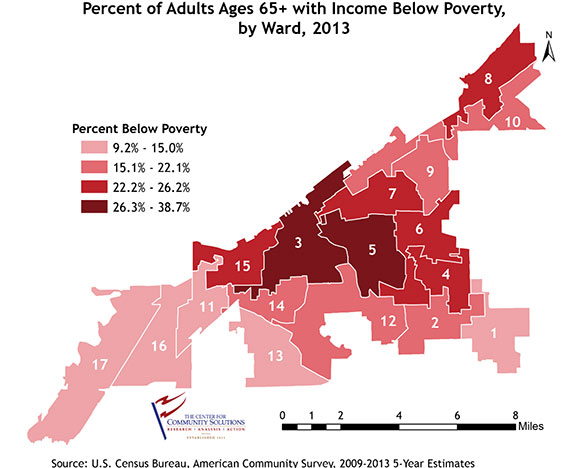

Cleveland officials have acknowledged the silver tsunami. In 2014, the city joined the World Health Organization’s Global Network of Age-Friendly Cities, a worldwide effort to prepare for aging populations and increasing urbanization. As part of that partnership, the city asked the Center for Community Solutions to study how area seniors were doing. The resulting January 2016 report found almost 22 percent of Cleveland residents 60 and older live in poverty. The report says seniors worry about crime and safety, and that they need help maintaining their homes and connecting socially.

The study led to a three-year action plan with a host of recommendations, including a falls-prevention campaign, age-friendly business developments, additional senior-companion volunteers and home-repair programs. It also calls for identifying gaps in long-term care and fighting workplace age discrimination.

Meanwhile, Western Reserve has lobbied the Ohio General Assembly to examine malnutrition in seniors, and a legislative commission is due to release a report next year. Also, the agency is planning a campaign to address senior hunger.

“We have a tough road ahead but if we pull together like we have in the past we can do what’s right for seniors,” Beach says.

Challenging the housing industry

While government agencies and nonprofits work to keep seniors in their homes, the private sector is experiencing an increasing demand for independent senior apartments, assisted-living communities and nursing homes. Some seniors are moving by choice, others by necessity. Michael Deemer, executive vice president of Downtown Cleveland Alliance, says the 55 – 64 age group is downtown’s fastest-growing demographic.

“It’s consistent with what we’ve seen nationally among millennials and baby boomers,” he says. “They are looking for a place with diverse amenities that is less car-dependent with shorter walks. Downtown, you have easy access to buses. And healthcare is important for seniors; you have Cleveland Clinic, St. Vincent (Charity Medical Center) and University Hospitals.”

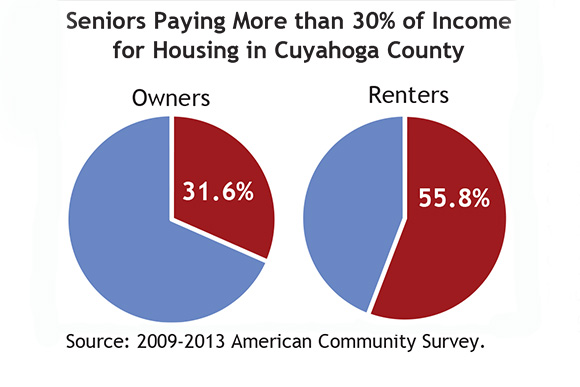

However, there is a problem. Cleveland proper lacks affordable, high-quality assisted living. Hence senior residents seeking it must often move outside the city where assisted living gets pricey.

"When you make less than $20,000 annually, you probably can’t afford assisted living,” Jones said.

"When you make less than $20,000 annually, you probably can’t afford assisted living,” Jones said.

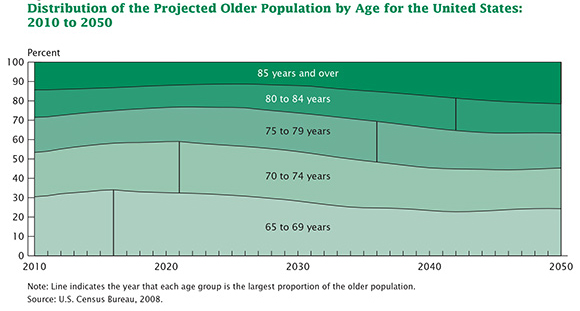

Even for those who can afford it, opportunities may become limited. In April 2016, Patrick Finley, Omni’s managing partner, told the Brecksville Planning Commission that a shortage of senior housing is becoming a crisis even as senior-living developments pop up throughout the region. According to numbers Omni mined from the U.S. Census Bureau, those ages 80 – 84 will grow by 81 percent nationally between 2015 and 2030, bringing that population from 5.8 million to 10.5 million.

“That’s significant,” Sinicariello says. “How do you serve an additional five million seniors?”

The demand is so great that Omni has turned its attention almost entirely to senior living developments. The firm has started projects in Strongsville and Westlake, and is partnering with Danbury Senior Living in North Canton to build senior housing in Hudson, Tallmadge and Massillon.

Sinicariello says new senior housing is needed to reinforce and replace aging stock. He says 56 percent of independent senior apartments in the United States are at least 25 years old, and 27 percent of assisted-living communities are older than that. Conversely, newer facilities have amenities baby boomers desire such as technological devices and all-day dining, and while care levels might vary, Sinicariello says his industry recognizes that senior developments are not just ordinary businesses.

“We are part of the community,” Sinicariello says. “When you drive by, you say, ‘My mom’s staying there,’ so it has a completely different impact. There is a connection to you and the community that is much different than any other business.”