Closer look: the local impact of Social Security reform

At one time, retirement planning was likened to a three-legged stool. Once people stopped working, they supported themselves with pensions, savings and Social Security.

But two legs of the stool have broken. Programs that employees must pay into have replaced those traditional, employer-funded pensions. Savings are bleak; almost half of American families have no money set aside for retirement For many elderly people—especially those who are low-income—the Social Security check is the only way to make ends meet.

And now that third leg is shaky.

A bill introduced by Rep. Sam Johnson of Texas, proposes drastic changes to the Social Security Trust Fund that are characterized by reductions in benefits. Experts say that strategy could have severe consequences in Cleveland, which has a high percentage of aging low-income residents.

In 2015, 250,000 Cuyahoga County residents received Social Security, according to figures from the Social Security Administration. More than two-thirds got retirement benefits, whether as workers, spouses or children.

There’s no dispute that the Social Security Trust Fund is in trouble. According to the Social Security and Medicare Boards of Trustees annual report, by 2034, money will have run out for both retirement and disability benefits. If that happens, recipients will see checks cut by more than one-fifth.

At issue is the fix—and Rep. Johnson's proposal is getting the most attention. The Texas Republican chairs the Social Security subcommittee of the House Ways and Means Committee.

Johnson’s solution for saving Social Security doesn’t include adding revenue to the fund. Instead it relies heavily upon cutting the amounts that folks receive from the entitlement. For example, his plan would raise the age for full benefits from 67 to 69.

“The new retirement age better reflects Americans’ longer life expectancy while maintaining the age for early retirement,” Johnson said in a press release.

It would also cut the cost of living allowance for retirees whose adjusted gross income is more than $85,000 ($170,000 for couples), while changing the measure of inflation that determines the cost of living allowance overall. Johnson called this “modernizing how benefits are calculated to increase benefits for lower income workers while slowing the growth of benefits for higher income workers.”

He introduced the plan in December, right before the Congress went on recess. He will have to reintroduce it now that a new session has begun.

One reform, different impacts by population, neighborhood

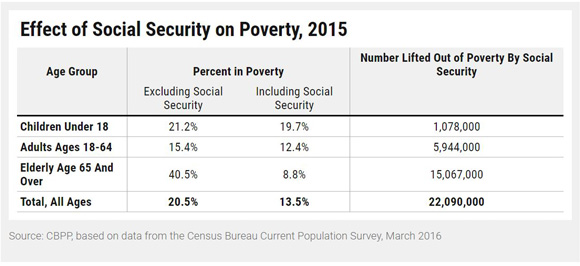

Social Security keeps many elderly afloat. Without the monthly check, roughly 45 percent of people aged 65 and older would be impoverished, according to a study from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. About 41 percent of older Ohioans would be poor if not for Social Security.

John Corlett

John Corlett

“I think people don’t think there is as much poverty among older adults as there is,” says John Corlett, president and executive director for the Center for Community Solutions, a Cleveland-based think tank that researches health, social and economic issues. “I think there’s this notion that Social Security sort of solves that. It’s not particularly accurate.”

The program is even more crucial for African Americans and Latinos. Without the benefit, about 45 percent of elderly Latinos and 50 percent of African American elderly would be destitute.

But Johnson's overhaul could have extensive consequences for those same people.

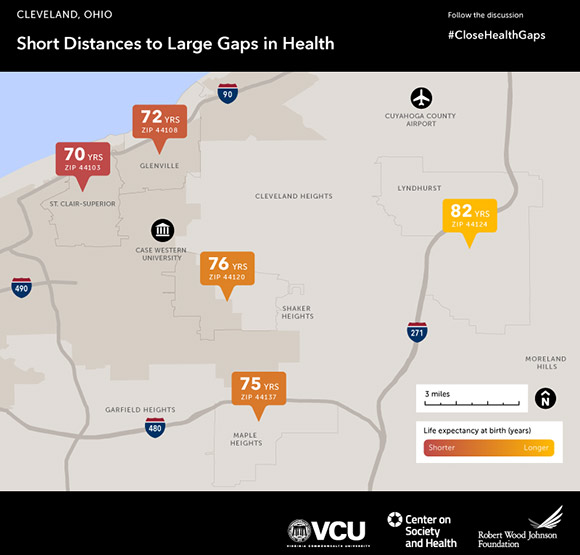

Raising the age for full benefits, for example, would harm residents of neighborhoods such as St.Clair-Superior, where life expectancy is just 70 years—nearly nine years shorter than the national average.

“It means that those folks would pay into Social Security for their whole life and never collect anything,” Corlett says. “In a city like Cleveland, which has shorter life expectancies and high rates of senior poverty, [raising the age eligibility] would create even more hardship.” But that hardship is unequal. Just 12 miles away in Lyndhurst, life expectancy is 82.

He added that those who work physically demanding jobs might have to retire early, and thereby accept a smaller check.

“A lot of people … are in situations where their health doesn’t allow them to keep working,” says Corlett.

Crippling a formidable economic engine

Terry Hokenstad

Terry Hokenstad

Terry Hokenstad, a professor at the Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences and Case Western Reserve University's School of Medicine says the consequences of a plan like Johnson’s would be far-reaching.

“[Those changes] would mean less money coming in Social Security—money provided at a later life date—and also less money coming in a yearly cost of living increase,” says Hokenstad. “This could do nothing but hurt blue-collar workers and consequently, the amount of money coming into Cuyahoga County.”

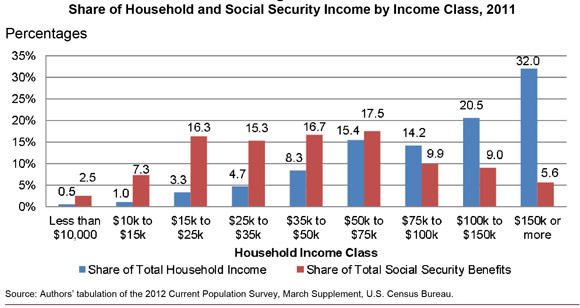

Part of the reason is that blue-collar and service workers often don't have other retirement income sources. Hokenstad notes that white-collar workers are more likely to have income from defined contribution plans or investments to complement the Social Security benefit.

“[The] upper-income population depends on Social Security much less,” he says. “It may be 10 or 15 percent of what their retirement is, while for lower income groups it might be 80 percent.”

Declining personal incomes wouldn’t be the only effect of Social Security overhaul. A 2012 study by AARP concluded Social Security supported more than 9.2 million jobs and $1.4 trillion in good and services nationally. Put another way, every dollar paid in Social Security generated two dollars of spending.

“Millions of Americans are employed because of Social Security benefit spending and thousands of small, medium, and large businesses exist in whole or in part because of the effect of Social Security on our economy," says Hokenstad. "Every state and every community feels these benefits.”

That’s because most folks don’t save those Social Security dollars. They spend them—to the profit of groceries and restaurants, as well as physicians and other medical services.

Instead of cutting benefits to make Social Security solvent, Hokenstad supports raising the income ceiling for Social Security, which denotes the top taxable amount on which each of us pays Social Security tax (6.2 percent, which is then matched by the employer). The cap was $118,500 in 2016 and will increase to $127,200 this year. Hokenstad, however, believes it should be $150,000.

“That would decrease, rather than increase income inequality,” he notes. “That would hit the higher income groups more, and not mean lower income groups would have to wait a couple more years until they got Social Security.”

This article was made possible in part with the support of a journalism fellowship from New America Media, the Gerontological Society of America and the Silver Century Foundation.