Stuck in Cleveland: Riders struggle to use public transit to get to work

Marvetta Rutherford’s bus won’t get her close enough to her temp job tonight.

So, after a five minute wait—the #15 bus is late to her stop in the Union-Miles neighborhood—and a 20-minute ride, the 63-year-old grandmother must hoof it the extra 30 minutes on a hot Friday afternoon through downtown Cleveland. She’s headed to FirstEnergy Stadium, where she’s working food service for a local high school’s prom.

Marvetta Rutherford, a spokesperson for the advocacy group Clevelanders for Public Transit, waits at a bus stop in her neighborhood of Union-Miles.“If you work at the Browns stadium, this is what you have to do, if you don’t catch a rideshare or whatever,” says Rutherford, a member of the citizen advocacy group Clevelanders for Public Transit (CPT). “There is no bus that takes you there.”

Marvetta Rutherford, a spokesperson for the advocacy group Clevelanders for Public Transit, waits at a bus stop in her neighborhood of Union-Miles.“If you work at the Browns stadium, this is what you have to do, if you don’t catch a rideshare or whatever,” says Rutherford, a member of the citizen advocacy group Clevelanders for Public Transit (CPT). “There is no bus that takes you there.”

There is a Blue Line rail stop near the stadium, but it’s been closed since fall 2020. Rutherford walked past a sign on the glass door informing riders the stop will be up and running again in “spring 2021.”

Northeast Ohio residents’ ability to get to work by public transit has been in the spotlight in recent years, with the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority’s (GCRTA) NextGen route redesign, implemented in June 2021, attempting to improve service frequency and job access.

Also, to specifically address the issue, the Fund for Our Economic Future granted $1 million in funding from its Paradox Prize to local agencies (you can read more about that here).

This attention is warranted but has yet to lead to meaningful change, Rutherford and other transit advocates say. Funding cuts in recent years combined with deferred maintenance and outmigration of the population have hurt the system to the point that remapping, while it has helped address transit issues in some neighborhoods, is not enough, they say.

Delays and deferred maintenance

The sprawl is real. A Brookings report found that the Cleveland metropolitan area experienced the largest drop in the number of jobs located near the average resident from 2000 to 2012 among the 96 largest metropolitan areas in the U.S.

And a 2015 Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland study outlined that half of Northeast Ohio’s top 10 employment centers—geographical areas where jobs are clustered—had access to 15% or less of the regional workforce. That study also found that jobs were least accessible for workers with only a high school degree, in positions that paid less than $1,250 per month.

Rutherford doesn’t have a car and relies on public transit to get her to temporary jobs, which are often in downtown Cleveland or on the East Side. She says it’s hard to find a route that can get her to those jobs within 45 minutes. Plus, she has arthritis in her legs and hips, so it’s not an easy journey when she has to walk a lot.

“You’re not going to be able to do that… if you’re going from here [Union-Miles] downtown, if you’ve got to make a connection, if you’ve got to go to an industrial park, or God forbid, if it’s what they think is non-peak hours,” she says.

Chris Stocking, a near West Side resident and member of CPT, used to take the Red Line train to get to his workplace on the East Side. But he’s stopped relying on it because of too many delays and breakdowns. From what he’s witnessed, the railcars on the Rapid’s Red Line are far beyond their useful life, and often need maintenance or have malfunctions—including smoking motors, which means the entire railcar must be evacuated and riders must wait for a replacement car.

“If the train is delayed 10 minutes, now I have to wait half an hour for my next connection,” Stocking says. “You can’t have maintenance and broken rail cars all the time and expect people to take it, because it’s just not reliable.”

Joel Freilich, director of service management for the Greater Cleveland RTA.Joel Freilich, GCRTA’s director of service management, calls Red Line service reliability “still pretty good,” but acknowledges “that if we keep using these Red Line cars for another 10 years, our service reliability would be very poor, so as a result we have a big effort underway right now to replace every Red Line car we own.”

Joel Freilich, director of service management for the Greater Cleveland RTA.Joel Freilich, GCRTA’s director of service management, calls Red Line service reliability “still pretty good,” but acknowledges “that if we keep using these Red Line cars for another 10 years, our service reliability would be very poor, so as a result we have a big effort underway right now to replace every Red Line car we own.”

Lynn Nilgess, 64, also lives on the near West Side and commutes to her job at the Cleveland Museum of Art as a security guard. She can either use the bus, with two transfers, or walk 15 to 20 minutes to a Red Line station. Either way, it takes about an hour for her to get to work and another hour to get home. The delays on the Red Line don’t help.

“Generally, what’s been happening is it goes out over the weekend, so that’s when I’m working, so that makes it hard,” she says.

And thanks to spotty weekend service, “some days, if I take the bus and I manage to get downtown, there’s a chance I could have to stand and wait an hour [for the second bus],” she says.

NextGen opportunities

In the planning leading up to the NextGen redesign, riders identified easier connections to work as a necessity, Freilich says.

The system redesign has resulted in significant improvements to service frequency in many parts of the Greater Cleveland area, he added—and with it, there is improved job access for many riders. Freilich says the number of jobs located within a half-mile of a frequent service line—defined as a bus or train that arrives every 15 minutes—increased by 25% from that redesign. And the number of residents who live within a half-mile of one of those frequent service lines doubled, he says.

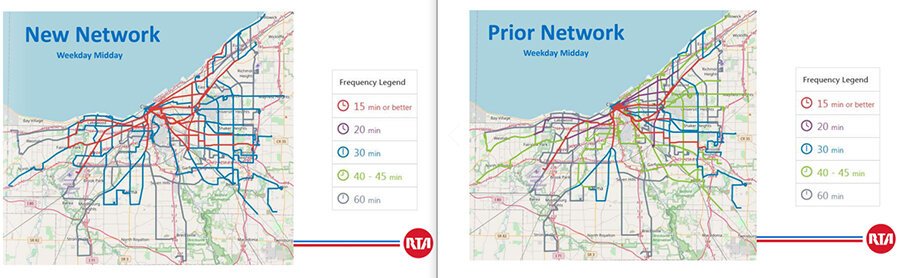

RTA routes throughout the greater Cleveland area before and after a redesign of those routes that was implemented last year.

RTA routes throughout the greater Cleveland area before and after a redesign of those routes that was implemented last year.

“That not only helps you get to work, it helps you get to absolutely everything else you might need to do,” Freilich says.

The redesign also improved the frequency of GCRTA’s transit options during the weekend and evenings too, recognizing that not everyone works a typical 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday-through-Friday schedule, Freilich says.

Even before the redesign, the Federal Reserve’s job access and public transportation report mentioned earlier in this story found some additional positives with the GCRTA’s services. The Cleveland metropolitan area in 2015 ranked above average in terms of transit coverage and was in the top 20 of all metropolitan areas in the country for service frequency both in the city and its suburbs, the report explained.

And a $6 million project is underway to stabilize the bridge that supports the Blue Line’s waterfront line that advocate Rutherford was unable to use. The project is set for completion in 2023, according to GCRTA spokesperson Robert Fleig.

Additionally, GCRTA has enough funding to replace the Red Line railcars and is currently seeking proposals from manufacturers to do so. The entire project to replace the GCRTA’s aging fleet of railcars is set to cost $300 million—one of the most expensive projects in the system’s history—and will replace 40 heavy and 34 light rail vehicles that are almost 40 years old, exceeding their design life, Fleig says.

What else can be done?

Robert Pfaff, visiting assistant professor in the Department of Urban Studies at Cleveland State University, studies public transportation.

He says replacing vehicles and improving transit infrastructure can be expensive and argues that greater investment is needed in public transit in order to make it more convenient, which would then encourage ridership. Cleveland’s ridership rate is less than 5%, Pfaff says, compared to larger cities with more well-developed public transit systems where car use is disincentivized, like New York City and Washington, D.C.

Replacing vehicles and improving transit infrastructure can be expensive and greater investment is needed in public transit in order to make it more convenient“A good city plans this comprehensively—and works to expand dense zoning, with funding for public transit, as well as other pedestrian/biking facilities,” Pfaff says.

Replacing vehicles and improving transit infrastructure can be expensive and greater investment is needed in public transit in order to make it more convenient“A good city plans this comprehensively—and works to expand dense zoning, with funding for public transit, as well as other pedestrian/biking facilities,” Pfaff says.

Pfaff adds that major metropolitan areas like Cleveland are contending with decades of development patterns and policies meant to create more-rapid movement of cars through cities, often at the expense of pedestrians, bicycles, and public transit.

CPT’s Stocking observes that fare revenue only makes up about 15% of the GCRTA’s budget—and ridership overall has been down during the pandemic—so funding would likely need to come from other sources. He suggests a tax levy paired with reduced fares—fares have doubled in the past 15 years while service was reduced. Stocking says GCRTA has never been to the ballot box to seek such funding since its creation in 1975.

GCRTA spokesperson Natoya Walker-Minor says her agency is “not considering a tax levy,” although the GCRTA’s board president said in a 2018 statement that they would consider putting one on the ballot sometime in 2019.

Increased funding could pay for a host of other service improvements to coax riders back. Stocking and other CPT members say communication problems are another matter, however. The GCRTA discontinued text alerts to people’s phones about service disruptions in 2017, and currently relies on a cellphone application; Stocking says adding back texts would help those without cell phones or data.

The Greater Cleveland RTA’s Blue Line waterfront stop has been closed since 2020, and won’t reopen until sometime in 2023.The GCRTA at one time also had digital display signs posted near busy stops, but they displayed inaccurate information, Stocking says. Most of those signs have been removed due to problems with the vendor, Freilich says.

The Greater Cleveland RTA’s Blue Line waterfront stop has been closed since 2020, and won’t reopen until sometime in 2023.The GCRTA at one time also had digital display signs posted near busy stops, but they displayed inaccurate information, Stocking says. Most of those signs have been removed due to problems with the vendor, Freilich says.

“We are interested in expanding that, funding permitted,” Freilich says. “We’re also working to improve the underlying data because… if it’s wrong on the cellphone then it’ll also be wrong on any fixed and installed sign.”

There are other small touches that could help encourage more ridership, too. Nilgess, the art museum employee, says the addition of a restroom and somebody cleaning the West Boulevard Red Line station more often would help make it more welcoming.

“When I get on the elevator I have to walk through puddles of urine,” she says. “...and I have had to walk past piles of feces.”

One of the big issues facing the GCRTA is urban sprawl—with decent-paying jobs increasingly being located farther outside of more frequent-service bus lines.

Freilich says it will take employers, local governments, and the GCRTA working together to improve that issue, whether it be employers creating shorter access roads to factories or cities sharing some of the cost of creating a new bus stop.

“It’s helpful for them to think about how workers will come to work if they are using a bus,” Freilich says.

Read about more examples of how local agencies are addressing the transit-to-work gap here.

This story is a part of the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative’s Making Ends Meet project. NEO SoJo is composed of 18-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland. Email Conor Morris at cmorris40@gmail.com.