Cleveland insider: curator's love of animals proves timeless

As a young animal keeper at Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, Tad Schoffner knew when he had gained acceptance from the approximately 120 rhesus monkeys on Monkey Island. It was when they started ignoring him, but only because they trusted him.

That allowed Schoffner, after he had fed the monkeys and cleaned the exhibit, to sit among them and observe. He noticed that a dominant male held sway. The male wasn’t the biggest in the group but he had established himself as one tough monkey.

“I found it funny that he would be on one side of the island, and a squabble would break out on the other side, and he would just stand up and look at them, and that would stop everything,” Schoffner says. “It was a view into the dynamics among animals the average zoo visitor never sees.”

Cleveland Metroparks Zoo curator Tad Schoffner

Cleveland Metroparks Zoo curator Tad Schoffner

Now 40 years later, Schoffner is one of two animal curators at the zoo, having risen through several management positions. He’s worked at the zoo, and with most of the animals there, longer than any other current employee.

“The only living specimen that has been here longer than me are the Aldabra (giant) tortoises,” says Schoffner, 62. “They came here in 1955. I’ve outlasted everything else.”

As curator, Schoffner oversees the Primate, Cat and Aquatics building, as well as the RainForest, commissary and Sarah Allison Steffee Center for Zoological Medicine. He coordinates animal breeding with other zoos throughout North America and helps set animal-care standards.

“The level of care at every zoo has changed so dramatically during my career,” Schoffner says. “It’s so rewarding to see how it’s progressed.”

Andi Kornak, the zoo’s director of zoological programs and veterinary services, says Schoffner’s forward thinking is one of the reasons she promoted him to animal curator almost four years ago.

“He has an in-depth knowledge and passion for not just the zoo but the entire Metroparks,” Kornak says. “He has evolved as zoos have evolved. He knows where they’re going and has a great affinity for that.”

Schoffner, a Lima native, has always revered animals. He majored in zoology at Kent State University, but married young, so he had to leave school and start working.

After the zoo hired him in 1977 to care for its monkeys, Schoffner became fascinated with primates, and educated himself by reading about them. Schoffner soon was appointed relief animal keeper, meaning he would fill in for absent keepers throughout the zoo. He grew familiar with just about every type of animal.

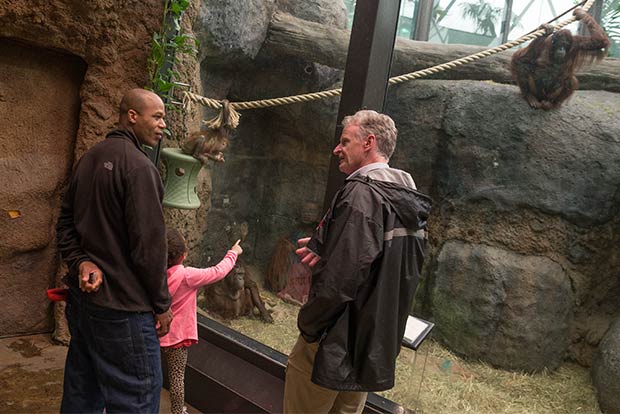

Cleveland Metroparks Zoo curator Tad Schoffner at the Orangutan exhibit in the RainForest

Cleveland Metroparks Zoo curator Tad Schoffner at the Orangutan exhibit in the RainForest

Schoffner was friends with Timmy, the zoo’s only gorilla at the time, before the animal was transferred in 1991 to the Bronx Zoo for mating. The transfer was controversial at the time because Timmy had bonded with Kate, an infertile female, and some believed it was wrong to separate them.

Timmy ended up fathering 13 offspring in the Bronx. That impressed Schoffner because Timmy was taken from the African wild when he was only 4 years old – something that doesn’t happen today because most zoo animals are bred in captivity – and his birth family never had a chance to school him in gorilla behavior.

“Working with Timmy was great,” Schoffner recalls of the beloved primate who died in 2011. “He was a unique personality. He was very shy and showed a gentle demeanor despite his imposing size – he weighed about 450 pounds – and occasional demonstrative behavior.”

Schoffner, always a cat lover, was next asked to care for the zoo’s tigers. It was a learning experience of a different kind.

Tad in 1980 with a Diana Monkey that was born at the zoo

Tad in 1980 with a Diana Monkey that was born at the zoo

“These were animals that could potentially kill you if you made a mistake,” Schoffner says. “So you don’t do stupid things. You build your relationships with the animals but there’s always a line you don’t cross. If you do something unexpected, and they become upset or scared, they will resort to their instinctive behaviors.”

That meant Schoffner never entered an enclosure while a tiger was inside. He never even stuck his fingers through the cage.

“I would find myself checking, double-checking and triple-checking doors and locks,” Schoffner says. “It almost feels like you’re paranoid but it’s a good paranoid to have. You always have to think about where you are and where the animal is.”

That said, some tigers expressed affection toward their caretaker. When they saw Schoffner approach, they greeted him with a calm, “chuffing” sound and rubbed their ears against the cage.

“In many ways you can see similar behaviors between large cats and your housecat, with the obvious exception being that tigers are wild animals, extremely powerful and potentially very dangerous,” Schoffner says.

Mokolo the Gorilla entertains the crowd at the RainForest

Mokolo the Gorilla entertains the crowd at the RainForest

After five years hanging with tigers, Schoffner was promoted to lead keeper in the primate and cat building, his first supervisory position. Then, as animal care manager, he created the zoo’s animal enrichment program, which aims to duplicate natural conditions for animals so they are physically and mentally stimulated.

A well-known example is African Elephant Crossing, which opened in 2011. The exhibit gives elephants more room to wander than ever before and houses rodents and birds that elephants might encounter if they lived in Africa.

Also, instead of throwing food on the ground for elephants, grub is placed in hanging feeders, because in the wild, elephants must stretch to the trees for their dinner.

Meanwhile, for primates, food is hidden inside boxes. Apes, who use tools in the wild, must take the boxes apart in order to eat.

Schoffner knows some people will oppose zoos no matter how much animal care has improved over the years. He sometimes chats with zoo opponents.

“All I can tell them is that, working around animals for all these years, I know the amount of attention, care and emotion that goes in caring for them properly on a daily basis,” Schoffner notes. “You may not like zoos, but you can’t doubt the dedication toward the animals that we have.

"We put our lives into the care of animals.”

Cleveland Metroparks is part of Fresh Water's underwriting support network.