Tethering Cleveland's charter and district schools to bring quality education to all

Veteran educator Paige Baublitz-Watkins has a long history working with gifted students in Northeast Ohio. She also relies heavily on data to direct her and her staff on how to give students the best education while also focusing on creative programs to improve performance.

Those qualities have made her a proactive, results-driven educator in both Cleveland’s charter schools and within the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD).

Paige Baublitz-WatkinsAfter two years as director of Cleveland’s Menlo Park Academy, a K-8 charter school specializing in gifted students, Baublitz-Watkins - or "Ms. BW" as the kids call her - took the reins as principal of Riverside School in 2014. The pre-K-8 CMSD school had historically performed well within the district, but was in need of a fresh approach.

Paige Baublitz-WatkinsAfter two years as director of Cleveland’s Menlo Park Academy, a K-8 charter school specializing in gifted students, Baublitz-Watkins - or "Ms. BW" as the kids call her - took the reins as principal of Riverside School in 2014. The pre-K-8 CMSD school had historically performed well within the district, but was in need of a fresh approach.

Since Baublitz-Watkins took over, Riverside’s state report card has improved. To achieve this, she spent a lot of time delving into performance data and considering programs that worked at Menlo Park in order to determine what exactly marks student success at Riverside. “We can have kids growing, but not achieving.” she explains.

Sometimes it takes a little reading between the lines. Baublitz-Watkins notes that a student who has been a low performer may rarely achieve district or state standards for a variety of factors. “However, if that student and teacher understand the growth that is occurring toward that achievement bar," she says, "we have a better gauge on what it takes to get there. That is what the state value-add is all about: not just that students achieve but that they grow."

This philosophy is exactly what the CMSD aims to achieve by having teachers like Baublitz-Watkins move from a charter school to a district school in Cleveland, or vice-versa. The experience gained at each school brings a well-rounded approach to education. While Menlo Park serves gifted students, Riverside’s diverse population represents a range of student abilities. Each school has its own challenges and successes to learn from, says Baublitz-Watkins.

“I would say that kids are kids no matter what the identifier may be,” she says. “However, Menlo is a unique school. You find student growth is more difficult to measure. I love Riverside and its diversity. It is important for students to see life from all angles. Riverside provides that opportunity and grows more complex relationships.”

Baublitz-Watkins is one example of the "cross-pollination" within the CMSD. While charter school leaders tend to be more entrepreneurial in their approaches to learning, district school leaders tend to have more access to resources. Connecting tethers between the two benefits both.

"We've seen this movement from one sector to another, and they are very different environments” says Piet van Lier, acting executive director of the Cleveland Transformation Alliance, the public-private partnership charged with ensuring high quality schools throughout the CMSD and overseeing the execution of The Cleveland Plan. “It’s interesting to see what people bring to their jobs, going from a charter to a district school.”

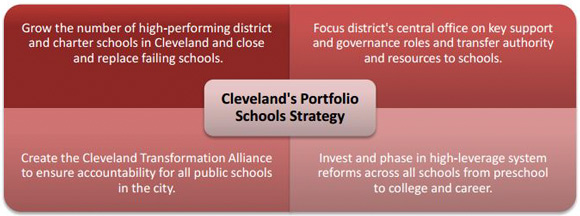

This cross-pollination transfers new ideas and methods between schools by forming a cohesive cross-section of best practices and addresses one primary element of Cleveland’s Plan for Transforming Schools: to make sure every child within the district has access to a high-quality education. In doing so, all schools in the district will see strengthened leadership.

“The basic idea is that these leaders who’ve moved from district to charter or charter to district have worked in different environments, and as a result, bring different perspectives of what the job is and what’s possible,” says van Lier. “They will also bring with them ideas or practices from their old setting to the new one.”

Baublitz-Watkins says her experience within the two camps, as well as having some good mentors, has brought a healthy cross-sectional approach to her methods as principal of Riverside. “All of those different experiences come to (bear) when you’re trying to make changes in city schools,” she says.

Real life experience

Some of those approaches are of a more entrepreneurial nature. At Menlo Park, Baublitz-Watkins was responsible for many administrative duties as director. Even though those administrative tasks are not usually associated with district principals, the experience helped prepare her when she became one at Riverside.

“I was required to fulfill all of those non-traditional aspects at Menlo and it served me well in my role at CMSD,” she says. “I also believe the expectations of the Cleveland Plan require administrators who have had non-traditional and charter experiences. This allows us to fulfill these expectations that were often addressed by the board offices in a large district.”

Van Lier stresses that it’s all about partnerships between charter and district school leaders to make sure every child get the education she needs. “The essence of the Cleveland Plan creates a new system of district and charter schools working together to meet the high standards for every school,” he says. “It’s about excellent schools, regardless of the provider.”

With more than 23 years of experience, including seven years with the Cleveland Heights-University Heights Schools as a gifted specialist and a one-year unpaid sabbatical with Campus International School (CIS), which included an internship at Garfield Middle School in Lakewood, Baublitz-Watkins garnered her share of hands-on experience. She also found solid mentors in CIS principal Julie Beers and Garfield principal Mark Walter.

“Starting a new school from scratch allows you to be more flexible in your thinking about what works or doesn't work in a school and be willing to challenge a status quo,” she says of her experience at the then-fledgling CIS. She credits Beers and Walters for her current success at Riverside.

“Learning from professionals who have competency in data and its relationship to curriculum taught me more than I ever received in course work,” Baublitz-Watkins says. “Practical hands on experience with those who create results made that work real.”

A new approach

Relying on data to create new programming at Riverside, Baublitz-Watkins has implemented a K-3 literacy program that has led to improved state scores and has transformed Riverside’s literacy report card from a B rating of 69 percent to an A rating of 87 percent. “We’re the only A in the district,” she boasts. “It’s definitely positive." The program has set an example the CMSD is using for other schools.

Baublitz-Watkins was able to improve the school's literacy grade by implementing an intervention program based on her research. Beginning in fall 2015, K-1 teachers now use assessment data to flexibly group students for 50 minutes each day to provide targeted small group literacy support. Group composition changes at least quarterly, based on student progress. Teachers in Grades 2 and 3 already use this approach in their classrooms.

Additionally, while at Menlo Park, Baublitz-Watkins attended a training on sensory rooms and studied sensory diets to cope with the number of twice exceptional students, which includes those who are both gifted intellectually and have a disability.

She created a sensory room at Menlo Park and has found the experience to be helpful at Riverside as well. “At Riverside, we have an even broader student population,” she says. “I felt they would benefit from this support and worked to make a full sensory experience happen for them.”

Riverside's sensory room has features such as aromatherapy, light displays, manipulatives, music and weighted blankets to stimulate or calm the students' senses. Baublitz-Watkins admits the room needs some work, which is something she plans to tackle this summer.

While most adults can find an equilibrium naturally, Baublitz-Watkins explains how sensitivity can differ from person to person using light stimulation in her own life as an example. “I am a low-light individual and my husband is high-light,” she says. “We constantly turn lights off and on in the home to create either more or less stimulation that our brains require.”

Students, however, sometimes need help identifying what is stimulating or calming. “Children have yet to learn what is stimulating their brains and are reactive to environmental matters,” Baublitz-Watkins explains. “A sensory room allows educators to determine baselines on what over- or under- stimulates a student and then teach them methods to control these factors for success in the classroom.”

Room for growth

In addition to new literacy and sensory programs, Baublitz-Watkins has enabled common spaces in the school to foster learning and social opportunities and created an advisory program for the upper school students. The advisory approach at Riverside places small groups of students with the same staff member for two-year rotations. “Riverside's are gender based with defined programming outcomes such as community service,” she explains.

She also believes in students being partners in their own learning. From that partnership comes success. “Student growth data and building trends need to be in teachers’ thoughts at all times,” explains Baublitz-Watkins. “This allows us to see without judgement where our compass must be pointed. I am always saying, ‘This is a no-judgement zone. We all own the data and we all own how to improve it.’ If teachers feel that you are on their side, working together, there is room to grow and glow.”

Baublitz-Watkins has implemented Monday meetings at Riverside as a time to go over schedules and other details, and also as a time to recognize and reward positive behavior. Teachers award students “brag tags” and “keys to success” for work well done. “We celebrate successes, celebrate birthdays and review the agenda,” she says. “It builds a sense of community.” Parents are also invited to the first Monday meeting of each month.

Living what you learn

In retrospect, Baublitz-Watkins cites four core factors she learned from her time at Menlo Park and Campus International as contributing to her success as principal of Riverside: Working with management to create and reconcile a budget; creating a working flexible schedule; understanding best practices in hiring and legal matters; and taking “outside of the box” approaches to growth and achievement in the students.

But the number-one thing Baublitz-Watkins has learned from her experience is the importance of transparency in her work.

“Non-traditional approaches are scary,” she says. “I learned that what all stakeholders want in times of change is clarity of vision, accessibility, and consistency.”

Creating these things leads to success. “These factors create a relationship of transparency that will lead successful outcomes.”

The Cleveland Transformation Alliance is a Fresh Water sponsor.