A ‘vicious circle of red tape’ for people struggling to navigate aid for utility bills

Janet Cook’s utility bills are stacking up and she doesn’t have enough money to pay them.

The 62-year-old Clevelander’s main source of income is monthly Social Security disability checks. Cook had been working part-time as an independent contractor, but lost the job due to COVID-19.

Cook is not alone.

It is estimated that nationwide households are $40 billion behind in utility bills and $32 billion in rental arrears—driven in large part due to income loss caused by COVID-19.

The difficulties for utility customers behind on their bills has compounded as pandemic moratoriums on disconnections have lifted. Now many people are receiving shutoff notices—leaving them to wonder where to turn next as the weather has turned colder.

Some assistance could come this month. President Donald Trump on Dec. 27 signed a coronavirus relief bill that includes $25 billion for rent and utility assistance—which would cover about a third of what American’s owe—though not all who need the money will be eligible. The relief bill prioritizes low-income families with the highest risk for being evicted, or already having a utility disconnected.

There’s other assistance out there, and utilities urge consumers behind on their bills to contact them to set up a payment plan. But that can be easier said than done.

Customers behind on their bills in Ohio have to navigate a confusing thicket of assistance programs. They need to find out who to call, navigate the myriad eligibility requirements, plus find old bills and other documentation.

Even then, they frequently encounter long wait times or far-off appointment dates to speak to an actual human.

It can mean a frustrating loop of phone calls that lead nowhere for people already struggling to make ends meet. Cook calls this maze a “vicious cycle of red tape.”

"You try to get help, so you call this number and never get an answer or you go online to make an appointment, but there's no appointments. It's a run-around," Cook says.

By the time she obtained the documentation requested as part of the application process, the time limit to submit that information had expired and she had to restart the entire process.

Cook, however, persevered. She’s received some assistance from CHN Housing Partners to help pay her gas and sewer bills, as well as the Salvation Army which helped with her electric bill.

But obtaining that help proved to be a bureaucratic challenge.

"All the paperwork you have to send in, the bills, verification of income, proof of residency,” Cook recalls of the experience. “I'm 62, so this is a lot of hassle.”

Recently Cook received a disconnection notice for her electricity from the Illuminating Company, run by FirstEnergy Corp. The private utility resumed shut offs in October.

Cook returned to the Salvation Army for further assistance. The Salvation Army told her that she had to contact HEAP (Home Energy Assistance Program) and PIPP (Percentage of Income Payment Plan Plus), before they could help her.

Cook says she tried to make appointments with both programs but there were none available, so she has now reached out to the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio (PUCO).

Cook says she appreciates the help she has received and sympathizes with those who are trying to provide her with answers.

"I understand that everyone is overloaded, and that these companies have their people working remotely," she says.

The end of moratoriums

When the pandemic first hit in March, most utilities instituted moratoriums that paused overdue bill collections and shutoffs. Starting in July, the some utility companies in Ohio lifted their moratoriums. In December, Cleveland, which operates municipal electric and water companies, lifted its moratorium.

The result has been tens of thousands of customers in Northeast Ohio who now owe larger bills with longer waits to access the limited assistance that exists.

The Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative surveyed utility customers to understand how they were dealing with the end of the moratoriums and obstacles they’ve run into when seeking help.

Most of the 25 respondents—who said they were seriously behind on both bills and rent—shared frustrations with the process. Some said their income was slightly over the limit to be eligible for aid programs, while others said they’ve been unable to get an appointment.

“They want mass amounts of paperwork,” one respondent wrote. “I don’t always have a working printer, or ink, or internet, or phone. I don’t have any spare time to gather and upload, either.”

Of those surveyed, all were struggling: Nine people had lost their jobs and seven had reduced hours; 10 had gotten sick with COVID-19; and another 10 were staying home to care for children.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Got similar problems? The Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative has created a guide to help people navigate the system of utility aid in NE Ohio.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The coronavirus relief measures enacted in December extend an eviction moratorium nationwide until the end of January. Ohio could receive as much as $778 million to make direct payments to landlords and utility companies, according to estimates from the National Low Income Housing Coalition. The state will decide how to dole the money out.

While the assistance will provide some relief, it only covers a fraction of the immediate need. Emily Benfer, a visiting law professor and founding director of the Wake Forest Law Health Justice Clinic in North Carolina, says many who receive relief tend to devote that money toward rent—to avoid becoming homeless.

This leaves utility bills unpaid, leading to disconnections, making homes unsafe places to live.

Hoping for "Hail Mary" pass

Lakewood resident Jennifer Toth is running out of both hope and options.

Toth has Lupus, an autoimmune disease, and has been on disability since 2004. Her health and a divorce caused financial hardships. The COVID-19 pandemic added an even greater burden to Toth's situation, with the need to buy PPE supplies.

Most of Toth's utilities are covered through her rent, but she's fallen behind in paying that bill, as well as her electric bill (not covered by her rent), leaving her to make difficult decisions.

"I have to choose between food and medicine, between medicine and a place to live, those basic things every day,” she explains. “Even though I do have insurance, the price of medicine is high and some of the medicines I take aren't covered.”

While Toth was able to obtain some financial help early in the pandemic from the CARES act, that money only lasted two months. Since then, she's turned to community agencies for help, but hasn't had much success.

Toth, who is single and childless, said there are few assistance programs for her situation.

Toth says that includes the Illuminating Company, which she said told her that since she was childless, there was nothing they could do for her.

"They're difficult to deal with, to get anyone on the phone," says Toth.

Christopher Eck, senior communications representative for FirstEnergy, says he isn’t able to comment on individual customer accounts, but does say that assistance is needs-based and doesn’t necessarily exclude single individuals or apply only to people with children.

The reality, Eck says, is some customers aren’t eligible for assistance because their income levels are too high, including those with disability income that exceeds the federal poverty guidelines.

What Eck outlines is a common problem. Larger families can earn more money and still be below the federal poverty level. For example, a single person making $12,760 or less a year is considered below the line, versus a four-person family earning $26,200 a year. That makes things challenging for people like Toth, who have a limited income that is just above the poverty level.

As the pandemic drags on, Toth says she is uncertain how she will be able to get caught up on the bills that she's fallen behind on.

She says she’s often been saved by what she describes as a last minute “Hail Mary” pass of help—from her church, as well as an anonymous benefactor—she’s worried that her small amount of good fortune is running out.

“This month has been difficult, but I'm hoping and praying that something will happen for rent assistance for this month, says Toth. “I have a call into the Lakewood Community Service Center. We'll go from there and see what happens.”

Confusion around moratoriums and disconnections

As the constellation of utility moratoriums ended last fall, calls to United Way's 2-1-1 Help Center spiked, with many unsure of where to go for help.

Requests made for help from two Cuyahoga County COVID-19-related assistance funds also spiked.

CHN Housing Partners, which administered city and county relief funds for renters, ran out of its $2 million in aid for utility bills by mid-December, with much of it going to Cleveland water and electric customers.

The other fund, administered by the Council for Economic Opportunities in Greater Cleveland (CEOGC), still is taking applications. Deadlines for spending that money were extended with the signing of the recent stimulus bill.

For some Cleveland customers, the lifting of the moratoriums, along with mixed messages from city leaders, has led to additional confusion and stress.

For example, Cleveland announced publicly that bill collections and utility disconnections had resumed as of Dec. 1. However, Cleveland Ward 16 City Councilperson and chair of Council’s Public Utilities Committee Brian Kazy, said recently that the city’s water department and Cleveland Public Power have an unofficial policy to not turn off residential services during the winter months.

Kazy said he “wasn’t aware” of any residential city water or power customers’ services being shut off since the city’s moratorium ended.

Jacie Jones, a volunteer organizer for Utilities for All, a Cleveland-based grassroots organization that advocates for accountability and equity from utility companies, says her group is demanding that the city continue its moratorium on shutoffs, among other changes.

Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson said at a recent city press conference that he thought the city typically did not shut off utilities during the winter months, but he was unsure if that was a formal policy.

When asked for clarification, a city spokesperson didn’t answer the question, but did say the city voluntarily follows the state’s “Winter Reconnect Order,” which allows customers to get reconnected or maintain electric or gas services once per winter (more info in our guide).

Regardless, Kazy and Jackson do make it clear that people need to pay their bills, noting that the city does offer payment plans and will direct people to other avenues for help. The number for Cleveland Public Power is (216) 664-4600 and the number for Cleveland Water Department is (216) 664-3130.

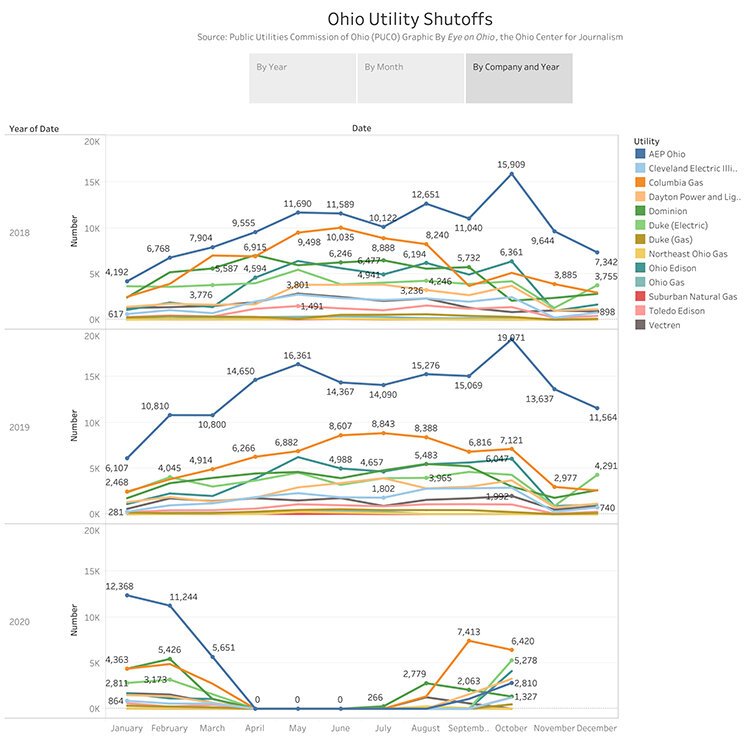

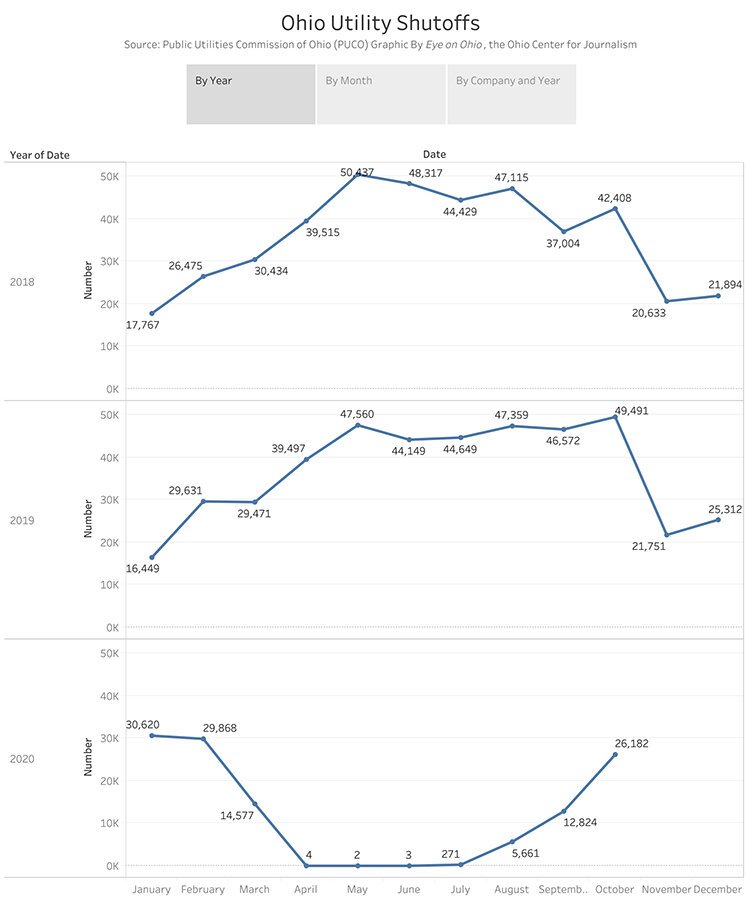

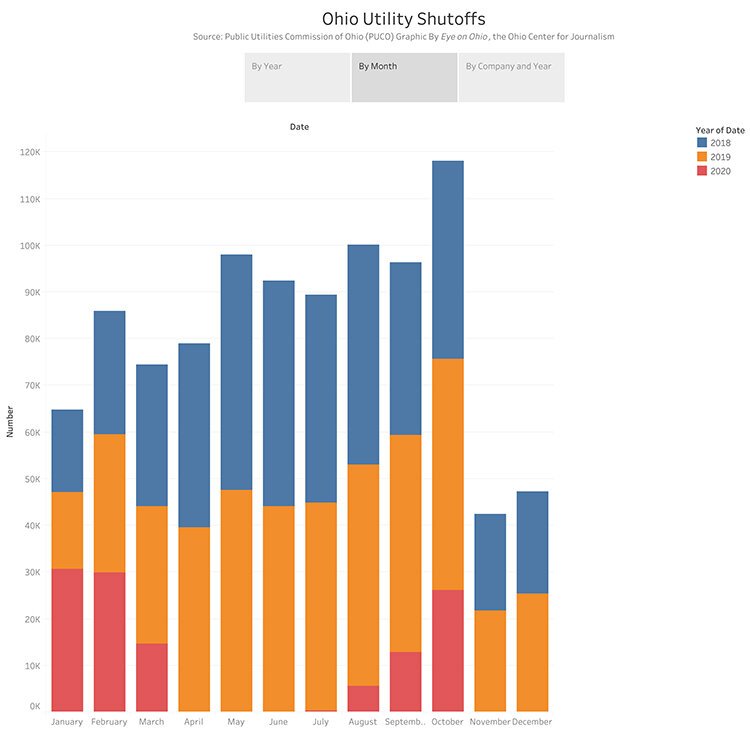

Meanwhile, private utility customers are still being disconnected from their services, although not as much as years prior. According to PUCO data:

- The number of electric utility disconnections so far this year—67,991—is far below the 304,807 that happened in all of 2019. The fewer disconnections in 2020 are due to the moratoriums that were in place.

- Even after the moratoriums ended, disconnection numbers have lagged previous years so far. For example, FirstEnergy’s three Ohio electric companies disconnected 6,569 customers in October 2020 (including 1,209 through the Illuminating Company), compared to about 10,000 customers disconnected in October 2019. But data for November and December is not yet available.

For his part, Eck, with FirstEnergy, said customers should contact First Energy—before they get a disconnection notice, if possible—if they are having trouble paying their bills. Eck says because First Energy might have more options available to customers who haven’t yet received that notice.

"We know this pandemic has hit folks particularly hard, especially now with people working and doing school from home,” Eck says. “They don't want to have a disruption in their electric service.”

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 20-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland. Conor Morris, a Report for America corps member, and Rachel Dissell, a Cleveland-based freelance journalist, contributed to this article.