Long shot: Vaccination campaigns move at the speed of trust

Vaccine hesitancy is nothing new

Fear of getting vaccinated is nothing new—millions of Americans report being afraid of needles. But, why is there hesitancy to the COVID-19 vaccine?

For Black Americans, it could be a response to the history of vaccinations and ethically compromised experiments, like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where doctors withheld treatment for Black men from 1932 until 1972 when a whistleblower finally brought it to the public's attention. It is but one, well-documented case in medical history that may be undermining confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine developed under the federal government's Operation Warp Speed.

Addressing the oft-cited Tuskegee Syphilis Study, Amanda Mahoney, chief curator of the Dittrick Museum of Medical History at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) casts doubt that COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among minorities can be traced to one event.

“You can lay a lot of this at the federal government’s feet because of unclear messaging in [2020],” she says.

A range of factors—including trust in authorities—influence the decision of whether or not a person will get the vaccine. A recent survey by a business group found that 24% of workers would refuse to get vaccinated if their employer required it.

“The COVID vaccine is different from mass vaccination programs,” says Mahoney, explaining that it was compulsory for children to get vaccinated during the smallpox epidemics at the turn of the 20th century. “Many of the vaccinations we are familiar with are for children—you have parents making decisions for their children and not themselves.”

Vaccine hesitancy spiked with British doctor Andrew Wakefield, who in a 1998 article in “Nature” magazine espoused the theory that a trace level of mercury in Mumps Measles Rubella (MMR) vaccines was linked to autism. A large study in 2002 and subsequent books like “The Doctor Who Fooled the World” by Brian Deer, refuted Wakefield's theory, but the damage was done. Wakefield’s theory was picked up and amplified on social media by micro influencers like model and actress Jenny McCarthy, who wrote a 2007 book on the topic.

Anti-vaxxers are typically white and affluent, says Mahoney. The seeds of the current anti-vaxx movement, however, were planted well before the early 2000s, she adds.

“There were early anti-vaccination groups in the 19th century, mostly pushing up against compulsory vaccination and rules like not allowing students who weren't vaccinated into schools,” Mahoney says. “They use fear around the safety of vaccines to get support from white, middle class mothers to fight against regulation of any kind. And the healthcare institutions have not done a great job of educating people how disease works.”

Dr. Rebecca Lowenthal, a family medicine specialist in the MetroHealth System, says healthcare providers are addressing misinformation head-on with patients.

“I tell patients, when I got my first [COVID-19] shot I didn’t get any symptoms,” Lowenthal says. “But the second [shot], I got sick for 24 hours. I want that sickness. It’s a good way to know your body is forming those antibodies.”

In Lowenthal’s opinion, doctors will gain ground on influencers moving forward. “If I have a good patient-doctor relationship, we can have an honest conversation,” she says. “Sometimes, being at higher risk is something they perceive,” which has been the case for pregnant women taking the vaccine.

“My understanding is there are no documented cases of fertility [being negatively impacted],” Lowenthal says. “I’m part of a doctor/mom group on the Internet. Most [of the women] are getting their shots.”

—Marc Lefkowitz

Robyn doesn’t doubt the dangers of COVID-19. As a medical assistant at a Cleveland hospital, she witnessed the virus’ impact firsthand.

“I’ve been on the front line since day one,” says Robyn, who requested her last name and employer's name be withheld out of fear of losing her job. She’s seen a coworker’s grandmother pass away from the COVID-19 and has cared for patients suffering from severe symptoms.

An estimated 28% of American healthcare workers have said they will “wait and see” before they get the vaccine, despite working on the frontlines.Robyn does have doubts about the COVID-19 vaccine, however. While she acknowledges that it’s an important step in fighting the coronavirus and saving lives, she’s skeptical about the positive numbers that Pfizer and Moderna are reporting.

An estimated 28% of American healthcare workers have said they will “wait and see” before they get the vaccine, despite working on the frontlines.Robyn does have doubts about the COVID-19 vaccine, however. While she acknowledges that it’s an important step in fighting the coronavirus and saving lives, she’s skeptical about the positive numbers that Pfizer and Moderna are reporting.

Although she hasn’t seen specific data that shows that Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are unsafe, Robyn still fears that the companies might not be reporting honestly. She points out that drug companies helped drive the opioid epidemic by hiding details about the high risk of addiction, and therefore shouldn’t be trusted.

“Medical companies like Pfizer, of course they tell you all the risks, and the risk is [bigger] than the benefits,” she states.

Mostly, though, Robyn worries that the vaccine was developed too quickly to ensure its safety.

“Nobody knows anything for sure,” Robyn asserts. “I would rather not be a guinea pig in the medical setting. I'll take my chances and do the best I can to prevent getting [the coronavirus].”

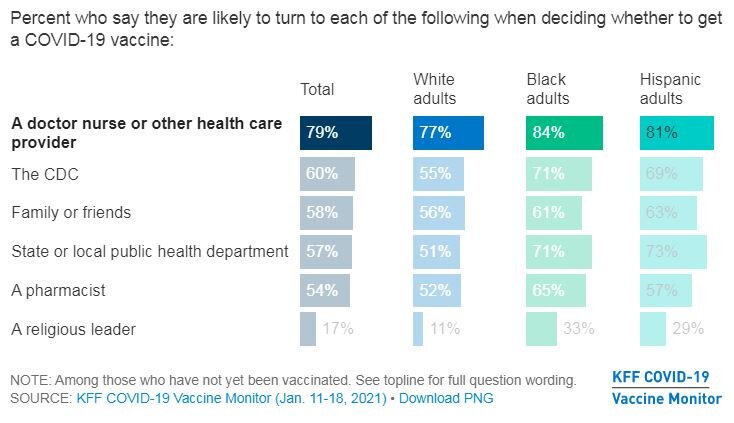

Robyn is not alone in her fears. An estimated 28% of American healthcare workers have said they will “wait and see” before they get the vaccine, despite working on the frontlines, in a high-risk field. While this hesitancy rate is slightly lower than that of non-healthcare essential workers (31%), it is significant because 80% of Americans in a January poll conducted by Kaiser Family Foundation said they would seek the advice of healthcare providers when deciding whether or not to get vaccinated.

Sources of mistrust

Amanda Mahoney, chief curator of the Dittrick Museum of Medical History at Case Western Reserve University, believes that healthcare worker’s mistrust is partially rooted in misinformation from the early days of the pandemic.

“Healthcare workers benefited... and suffered from speed of exchange of information,” says Mahoney, who is also a registered nurse. She says that early studies about COVID-19—such as those which claimed that the severity of the disease was based on people’s blood types—later turned out to be questionable.

“The lack of cohesive messaging eroded what little trust we had,” says Mahoney.

But Mahoney emphasizes that vaccine hesitancy—both among healthcare workers and others—isn’t just about lack of information. Rather, it is rooted in two different streams of history that have prompted mistrust across different groups, albeit for very different reasons.

One of those histories is that of the “anti-vaxxer” movement, which was flamed by false studies linking autism to vaccinations.

“There has always been the anti-government, anti-regulation involvement,” says Mahoney. “[Anti-vaxxer movements] use fear around the safety of vaccines to get support from white, middle class mothers to fight against regulation of any kind.”

The other history, though, is that of decades of unequal healthcare provision that discriminate against minority communities. Mahoney points out that minority groups have long been abused by the medical system, and not just in historical instances like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

“Our entire healthcare system massively abuses Black people by not listening to Black women’s pain,” says Mahoney. “[There are] algorithms used to triage patients that prioritize white patients with the exact same symptoms as Black people. A lack of trust in the healthcare system is warranted.”

A pilot study by Rubix Life Sciences found that during the pandemic, medical professionals have been six times more likely to provide treatment and testing for the same COVID-19 symptoms to White patients than Black patients.

This lack of trust influences people working within the healthcare system as well. It’s one of the primary reasons Sherena Williams, a dentist office employee, has decided to wait on the vaccine.

“You can’t put something out there and expect us to trust it,” says Williams. “The government are the people behind COVID and the death toll. [People won’t get the vaccine] until we feel in our hearts that we trust the government enough.”

Building trust

Still, a recent poll suggests that while people might not trust the government or healthcare system in general, they do trust their healthcare providers. Eight in 10 people said they would turn to a doctor, nurse, or other healthcare provider to decide whether or not to get a vaccine.

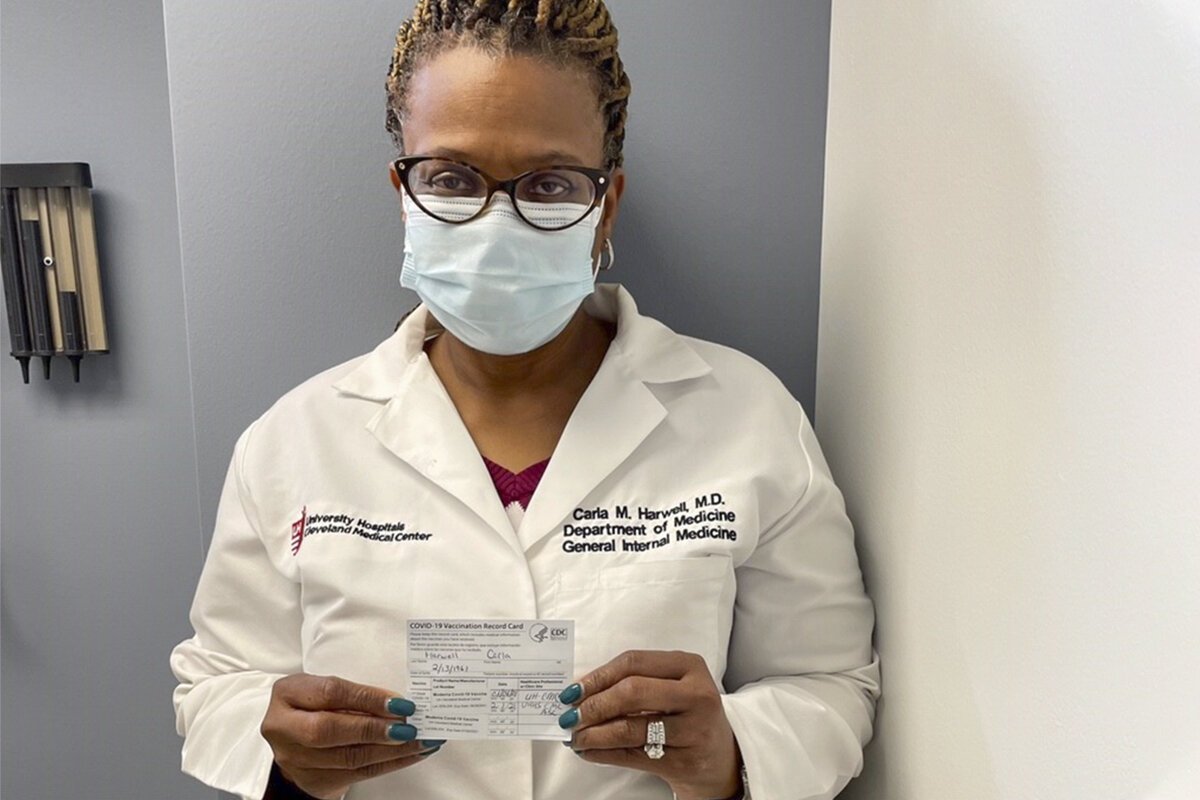

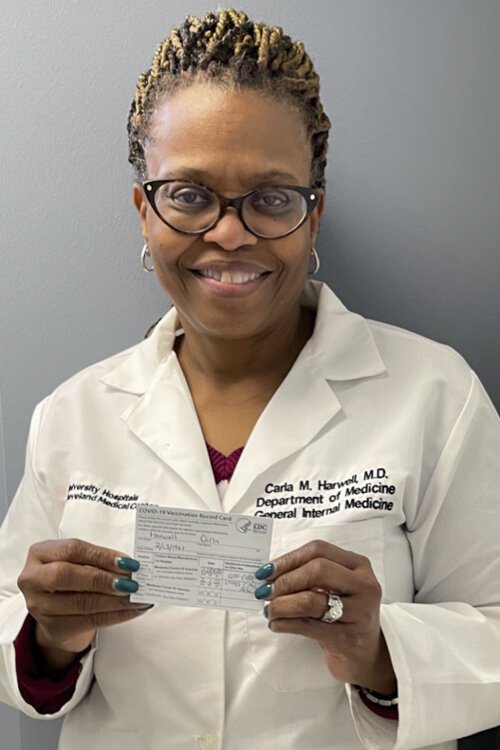

Dr. Carla Harwell, a physician at UH in Cleveland's Fairfax neighborhood, says the key to getting patients to take the vaccine is to acknowledge their fears while gently pushing back against rumors or misinformation.That personal trust is something that Carla Harwell, a physician practicing at University Hospitals Otis Moss Jr. Health Center in Cleveland's Fairfax neighborhood, said she can build on.

Dr. Carla Harwell, a physician at UH in Cleveland's Fairfax neighborhood, says the key to getting patients to take the vaccine is to acknowledge their fears while gently pushing back against rumors or misinformation.That personal trust is something that Carla Harwell, a physician practicing at University Hospitals Otis Moss Jr. Health Center in Cleveland's Fairfax neighborhood, said she can build on.

Harwell says the key to getting patients to take the vaccine is to acknowledge their fears while gently pushing back against rumors or misinformation they might have received on social media.

“You can’t just go from zero to 60,” says Harwell. “Sometimes I’m able to say, 'that [rumor] is not true and hasn't been proven.' You have to be able to empathize with your patients. When [you] empathize with somebody you are saying ‘I can understand why you feel this way. I hear what you’re saying.’”

Harwell believes that this kind of empathy and compassion is crucial for her to build trust with patients.

“I know I just try to educate,” says Harwell, “and be what I call a trusted voice for my community.”

Lessons from prior disease outbreaks show that trusted messengers like Harwell—whether they are doctors, religious leaders, or even social media influencers—can be effective in overcoming vaccine hesitancy.

In 2017, for instance, a measles outbreak hit the Somali population in Minneapolis-St. Paul, where mistrust of the government’s immunization efforts led to low vaccination rates. In response, the Mayo Clinic collaborated with Somali community groups in nearby Olmstead County to change messaging in an attempt to stop the spread. Mosque leaders and healthcare providers hosted town halls to address community concerns. Somali actors created YouTube videos. The result: vaccination rates increased, and of the 25,000 Somali immigrants living in Olmstead County, not a single case of measles was reported from 2017-2019.

Groups in Cleveland have used similar methods, relying on social media and trusted messengers to build momentum for the vaccine.

Harwell, for instance, appears in a YouTube video produced by UH to address coronavirus vaccine hesitancy among the African American community. In it, Harwell acknowledges the history of abuses, while also reassuring community members of the need to get the vaccine.

MetroHealth, likewise, collaborated with 20 Cleveland clergy to create a video to encourage congregation members to get the vaccine. The video includes interviews with faith leaders who acknowledge the history of inequality in healthcare, but say they are “putting their faith in science.” They try to allay fears by taking the vaccine on video, and urge their congregations to do the same.

Broader information campaigns, like The Conversation, a video series featuring W. Kamau Bell and Black healthcare providers addressing concerns about coronavirus and the vaccine, are showing signs of effectiveness. A Marist poll last week conducted by NPR/PBS NewsHour found there is no difference between racial groups planning to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, a change of significant proportions from polls conducted in December.

Healthcare providers take the lead

Individual healthcare providers have also taken steps to encourage hesitant community members. Medical assistant Christian Amuli of Neighborhood Family Practice has said he was initially wary of receiving the vaccine, despite having had COVID-19 earlier in the year.

“One of the doctors [at Neighborhood Family Practice] came and talked to me and said that the vaccine was okay, and that it would help protect my family,” says Amuli. “He told me he had taken the vaccine and nothing had happened.”

Originally from Congo, Amuli says that many people from Cleveland’s Congolese community had received false information about COVID-19. They’d seen videos on social media saying that the disease wasn’t real, and that it was merely a rumor being used by the government as a form of control. Now, Amuli says many in the Congolese community are concerned about the vaccine because of similar rumors they’ve read on social media, and because of videos being shared about people getting sick after the vaccine.

“When I decided to get the vaccine, at first I did it in secret. I knew [my community] would tell me not to do it,” Amuli laughs. “I actually waited to text my mom from work saying ‘I’m getting the vaccine.’”

Amuli shared his experience a few days later on the messaging app Whatsapp and to his 10,000 followers on Instagram. His friends all watched carefully to see if he’d develop side effects. After a few days, he reported that nothing had happened. As a result, Amuli said several of his friends told him they’ll take the vaccine once their age group is eligible.

And while these efforts by community messengers such as Amuli and Harwell won’t undo the decades of misinformation, they can begin to reframe the conversation around provider compassion. For Harwell, this means addressing her patients fears while also framing the conversation as a personal decision.

“I’m more afraid of Covid than I am of this vaccine,” says Harwell. “When I saw my cousin on a ventilator, COVID had a face for me.”

She says that experience and her care for her patients made her decide to get the vaccine.

“To be honest with you, I didn’t get vaccinated for myself; I was getting it for my elderly parents,” says Harwell. “I wake up as Carla Harwell with the same thoughts and fears as everybody else. I’m not going to lie and say I didn’t have any concerns. But, I follow the science. The human part of me said, 'you have to take care of your parents.' I can’t afford to go down and end up on a ventilator.”

See the first part in this series, A matter of trust: Inside prison COVID-19 hot spots, many inmates fear the vaccine, in last Thursday's FreshWater.

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 20-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland.

Sydney Kornegay is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Aidemocracy, The Columbia Star, and Observatario Economico. She has a master's degree in International Development and Economics from Fordham University and is the director of adult programming at Refugee Response in Cleveland.

Marc Lefkowitz is a sustainability consultant with more than 15 years of experience writing, speaking and advocating for a more sustainable Northeast Ohio. He served as director of the GreenCityBlueLake Institute and editor of its well-known blog at gcbl.org. He has a B.A. in English from Ohio State University and an M.A. in urban planning from Cleveland State University. He is a regular bike commuter and transit rider.