A road less traveled: The attempted revival of Willey Avenue

When developer Josh Rosen first visited the Fairmont Creamery on Willey Avenue in Tremont back in 2012 to consider it for an apartment redevelopment, he was surprised to discover the street even existed.

He’d lived in Tremont for five years, but had never used the winding, hilly road to get to Ohio City, the neighborhood to which the street connects. Instead, he’d always traveled Abbey Avenue, Willey’s straighter and much-more-visible neighbor to the north.

“It wasn’t until I was standing on the roof as part of our building tour, looking down, that I realized it was such a great connection,” Rosen remembers.

Though an odd and neglected one.

In many ways, the half-mile street is the scruffier, more rebellious sibling to Abbey, with which it runs roughly parallel. The sidewalks are discontinuous, asphalt patches cover gaping potholes, and cattails and reeds sway in the wake of passing cars – ghosts of a long-ago-buried stream.

For Rosen and his partners Naomi Sabel and Ben Ezinga, though, this half-forgotten landscape was a turning point in their decision to tackle the project.

“We like to look for a community benefit beyond just filling a building,” he says. “To us, Willey was it – a way to link Ohio City and Tremont. It not only gave us a purpose, but a solid narrative that we could talk about with investors and public partners.”

In early meetings with surrounding block clubs, the developers also vowed that the street’s revival would be a priority.

“We told people, ‘judge our success by what happens on Willey Avenue,’” Rosen recalls.

Marshy grass and reeds near the railroad tracks on Willey Ave

Marshy grass and reeds near the railroad tracks on Willey Ave

Flash forward to the present: The Creamery has been open a year, with nearly 60 residents and a handful of businesses.

With the dust settling, pressure is mounting to lift Willey from its neglected past to a more serviceable present. Calls for improvements are coming not only from people who live and work at the Creamery, but also from pedestrians and bicyclists looking for new ways to get between Tremont and Ohio City; from long-time landowners such as the Cleveland Animal Protective League (APL); and from other developers eyeing parcels nearby.

It’s the inverse of the more familiar Cleveland story of a once-vibrant street succumbing to abandonment. In Willey’s case, people are instead asking how to improve a street that’s been an afterthought for decades – so much so that no one’s even sure how to pronounce its name.

In recent weeks there have been some initial improvements, including cutting back some overgrowth. But making Willey more welcoming is proving complex, reflecting the street’s tangled land ownership, its environmental fragility and the suddenness with which it’s been thrust into the spotlight as a hot area for redevelopment.

Wild, wonderful Willey

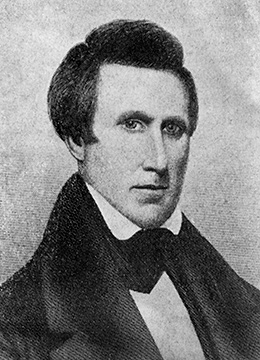

Willey Avenue has been around almost as long as Cleveland itself. It was originally called Kellogg Avenue, but in 1869 was renamed in honor of the city’s first mayor, John W. Willey. He was in office in the mid-1830s, when Cleveland was first booming as the northern terminus of the Ohio & Erie Canal.

Mayor John W. Willey

Mayor John W. Willey

The street’s up-and-down topography is due to its crossing the broad valley created by Walworth Run, one of the western tributaries of the Cuyahoga River.

“Like every valley and every ravine in Cleveland, it became industrial,” says George Cantor, chief city planner for the City of Cleveland. “Valleys were easy routes for rail lines, and then around the rail lines sprang up industries.”

And then came pollution. The industries that first inhabited Willey – including tar factories and slaughterhouses – used poor old Walworth Run as a dumping ground for their byproducts. By the 1870s, the stream became so dirty and smelly that the city decided to bury it underground. Today, marshy grass and reeds belie the area’s watery past.

But Willey was never heavily residential, and by the early 20th century, the few houses that remained on the street were mostly gone. They were replaced by businesses such as the Fairmont Creamery, a 100,000-square-foot hulk that processed and distributed eggs, ice cream and butter.

The APL is the street’s longest-running tenant. It’s been on the same site, across from the Creamery, since 1917.

Because the street served few pedestrians, it became a pass-through for cars and trucks. Sidewalks run only along certain sections of the street.

Sharon Harvey, the APL’s president and CEO, remembers interviewing for her job in 2007. “Willey felt like a forgotten part of Cleveland,” she says. “The surface was terrible, the Creamery was [graffiti] tagged and the street was desolate. It was just the APL and very little else going on.”

One of the APL’s veteran humane agents even jokingly warned her to look out for wayward livestock in the neighborhood. Back when that employee first started working, a few slaughterhouses were still active and cattle would sometimes escape their pens.

“I’ve never seen cattle, but we do get an occasional chicken or turkey wandering onto our property from people’s yards,” Harvey laughs.

The balance between the street’s industrial and environmental past and its increasingly residential present is part of what makes Willey so wonderful, says councilman Joe Cimperman, who adds that It’s one of the few places in Cleveland where you can experience the city’s natural, pre-urbanized topography – those cattails and hillsides -- alongside its industrial past.

“You’ve got the downtown skyscrapers to the north, but then you still have this gritty, soot-imbued landscape all around you,” Cimperman says. “It’s almost like a moonscape down there. You can’t make that up.”

Safer than it looks

Intriguing as it is, though, navigating the street by foot or bicycle can feel like an obstacle course.

Joe Lanzilotta often walks between his girlfriend’s apartment at the Creamery and Ohio City, where he works as a project manager at LAND studio.

The street’s hairpin turns combined with the disjointed sidewalk mean he has to be “hyper-vigilant” about traffic. Aggravating the situation is the fact that many motorists careen up and down Willey at screamingly high speeds, though the speed limit is 25 mph.

Off Willey Ave heading north

Off Willey Ave heading north

“I haven’t had a close call because I know what I’m looking for,” Lanzilotta says. “But it could be a real issue if you were a visitor or new to the street.”

Then there’s nighttime, when he says the lack of lighting and fellow pedestrians makes Willey feel creepy.

“I think it’s less real danger than perceived danger,” Lanzilotta says. “But there’s a sense that if something happened, there’d be no one to hear you scream.”

A search of Cleveland police reports from the past two years turns up no accounts of confrontations or attacks, only scattered traffic accidents.

Still, perceptions can be as important as reality.

“It’s a safe road but it doesn’t have the appearance of a safe road,” says Rosen. “And the appearance is what matters when you want people to re-inhabit an urban neighborhood.”

Cooperation required

The first steps toward improving Willey are clear, according to Rosen and Cimperman: Cut back all of the overgrowth and finish the sidewalks.

Simple as they seem, though, those solutions are requiring the collaboration of a patchwork of property owners who aren’t accustomed to working together.

Scranton Averell Corp., a real estate leasing company with properties in the Flats, also owns several properties on the street. One of is leased by Werner G. Smith Inc., which processes vegetable and fish oils. Another is vacant – its woods having been used for years as a campsite for a small homeless population.

A few weeks ago, the city issued Scranton Averall code violations on the lack of sidewalks on a two-acre property it owns on Willey, citing the company for being out of compliance with the federal American with Disabilities Act.

Thomas Stickney, Scranton Averell’s president, says the company plans to build sidewalks by next spring. The company hasn’t intended to be negligent or irresponsible, he says, they’re just catching up with changing times.

“Before, no one cared. But now people care,” Stickney says. “We’re thrilled about that. The more people are out and about, the safer and better the neighborhood becomes.”

Scranton Averell has also cleared significant brush and overgrowth from its land, dispersing of the homeless population.

“We’re not trying to be openly mean, but we don’t want anyone starting a fire back there,” Stickney says, adding that the company has “plans in the works” for its Willey properties, but he couldn’t yet say what.

The old Byrne Sign building at the corner of Willey and Train

The old Byrne Sign building at the corner of Willey and Train

Dave Walker, whose family owns the old Byrne Sign building at the corner of Willey and Train, is also excited about the street’s new direction.

He and his brother want to redevelop their red-brick building into artists’ studios. It’s currently used as storage for their Tremont-based printing company Dynamic Sign Inc. They’re still looking for financing, though.

“The building is in great shape, and we want to see it back contributing to the neighborhood,” Walker says.

He and Scranton Averell aren’t the only ones with development dreams. At least one other building, at the corner of Willey and Scranton, is under consideration for redevelopment. And the APL has a large vacant parcel behind its building that could become a prime spot for mixed-use development.

Additionally, Duck Island, the formerly sleepy area between Ohio City and Tremont at Willey’s west end, has become a hotspot for infill housing and property speculation.

A light touch

All those plans are creating pressure for a longer-term vision of the street’s future.

“There’s a lot of ideas bubbling around what Willey wants to be and could be,” says Corey Riordan, executive director of Tremont West Development Corp. “Where they’ll end up is hard to say because there are so many conversations happening at the same time.”

Cimperman, for one, wants a light touch -- one that preserves the street’s mixed legacies. “Just lay a bike lane, fix the sidewalk, cut the grass, light it up so people feel safe walking at night – and then get out the way,” he says.

He’s also trying to put the street on the city’s list for repaving next year.

Creamery developer Rosen can see Willey evolving into a healthy living district that plays off the Tremont Athletic Club and new walking-and-biking trails being built nearby. He envisions outdoor exercise equipment, green spaces and benches.

Whatever happens in the future, the APL’s Harvey says, she hopes it leads to connections beyond the physical.

“For so long, it’s been a place where we all did our own thing because it didn’t seem like much of a neighborhood,” she says. “I think that’s a miss for everyone. As Willey becomes more vibrant, there’s an opportunity for all of us to talk and work together more.”