freedom on two wheels: how some locals live car-free in c.l.e.

In American culture, cars have long symbolized individual freedom. From the TV ads depicting winding mountain roads to the drag-racing teens in "Rebel Without a Cause," cars have represented free-wheeling liberty since the dawn of modern media.

Yet Alex Nosse, an Ohio City resident who doesn't own a car, couldn't disagree more.

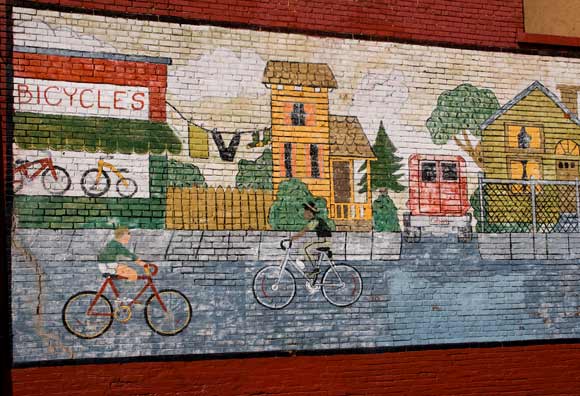

"People say having a car is freedom. But when I ride in a car, I feel isolation and enclosure, which is really the opposite," says the 27-year-old owner of Joy Machine Bike Shop, a new store on W. 25th Street that aims to help urban residents live a more car-free lifestyle. "To me, freedom is having a bike."

Jenita McGowan, an Ohio City resident who went "car-light" before giving up her car altogether last year, agrees. "I never have to worry about highway exits being closed, or finding a parking space," she says. "People thought I was crazy to go car-free right before winter, but it wasn't too bad. You just have to dress like you're skiing."

In recent years, biking advocates say they've noticed an increase in the number of people choosing a car-free lifestyle in Cleveland. Whether it's because of environmental concerns, the sting of high gas prices, the desire for a healthier lifestyle or simply the fun of flying downhill on two wheels, the number of bikes on the road is soaring.

"When we had a big gas price spike a couple of summers ago, the number of people that contacted us about going car-free doubled," says Jim Sheehan, director of the Ohio City Bike Co-op, a nonprofit that provides bicycle education to youth and adults.

Yet being car-free in Cleveland isn't for the faint of heart. Year-round bike commuters can't hop in their air-conditioned cars if it's 100 degrees or when there's a foot of snow on the ground in January. Daily commutes often involve negotiating pothole-filled streets while watching out for erratic drivers who think they don't have to share the road. Yet while going car-free has its challenges, advocates say it's more than worth it.

"I'd be foolish not to go car-free," says Nick Matthew, who works at Cain Park Cycle and is a member of the Cleveland Heights Bicycle Coalition. He cites benefits that include saving up to $8,000 dollars annually on gas, insurance, ownership and maintenance, ditching his gym membership and shrinking his carbon footprint.

How It's Done

If you're seeking to adopt a car-free lifestyle, bike commuters counsel a few simple steps that will make the experience safer, easier and more enjoyable.

Cyclists must act confident, treating their bike like any other vehicle on the road, explains Joy Machine's Nosse. "The key is you have to act like a car – if you're making a left-hand turn, get into the correct lane. Once you do it, you won't be intimidated."

Although Nosse says dealing with irate drivers simply comes with the territory – "I've had drivers attempt to run me down, but never successfully!" – these experiences are becoming rarer and rarer. "Because there are more bikers on the road, drivers are getting used to it, and there's less negative reaction over time."

Where you live also can determine the feasibility of going car-free. Dense, urban neighborhoods are natural fits, with amenities like restaurants, banks and grocery stores a short bike ride away. "I live on the near-west side, so things I need are at hand," says Nosse. The bulk of his shopping and entertainment takes place within a three-mile radius of home.

Living within biking distance to work also is essential. Jenita McGowan's bike commute to her job as Sustainability Manager with the City of Cleveland takes only 15 to 20 minutes. Cycling to meetings in and around downtown is actually faster than driving, she says. If she needs to be dressed up for a meeting, she takes transit or packs a set of formal clothes.

The Right Gear

Outfitting your bike with the proper equipment is essential. Experienced riders say that head and tail lights are crucial, as is a pump and tool and tire kit. Saddlebags or a sturdy rack is also helpful, but failing that, a good bag is nearly as good. "I carry a giant messenger bag around, and that works for me," says Andre Bacsa, a 24-year-old Cleveland Heights resident who has never owned a car.

Also, owning the right style of bike can make your daily commute much less painful, says Nosse. "You need a certain thickness of tires. That way you're less likely to go flat if you hit a pothole."

As for Old Man Winter, car-free proponents insist you can ride a bike in Cleveland year-round, as long as you dress for it. In addition to a change of clothes, cyclists need "really good rain gear, warm gloves and a hat for winter riding," says Nosse.

He dismisses the notion that biking in snow is dangerous, citing the availability of steel-studded tires for gaining traction in slick conditions and plastic cases that keep salt off your chain. Many cyclists prefer single-speed bikes because they're easier to maintain, he says. However, washing the salt off your bike can keep it from rusting.

Rules of the Road

Car-free proponents also say it's essential to know the rules of the road. "Our classes are like an owner's manual for your bike," says Ohio City Bike Co-op's Jim Sheehan. "Many people think they already know how to ride until they take our traffic safety class."

Jacob Van Sickle, Active Living Coordinator with Slavic Village Development and a regular bike commuter, says drivers need more education, too. "Teaching drivers how to deal with cyclists should be a mandatory part of their education," he says.

Finding safe bike routes in the city can be a bit of a challenge. "In the 1880s, the League of American Bicyclists lobbied for paved roads," says Sheehan. "Well, now we need a good roads movement in Cleveland. Bad roads can be life-threatening for cyclists – if you fall down under a truck, it's much worse than if you're in a car and hit a pothole."

Critical Mass

Of course, going car-free doesn't make sense for everyone. Andrea Joki, an artist who lives in University Heights, says she hasn't gotten rid of her car because she needs it to ferry art supplies to and from her studio. However, she regularly bikes to work and around the Heights for entertainment, shopping and errands.

According to Brad Chase of GreenCityBlueLake, the sustainability center of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, less than one percent of daily commuters in Northeast Ohio bike to work. However, that number is growing. Starting next month, bike commuters will be able to utilize a new downtown bike station, located at the corner of E. 4th and High streets. Additional bike-friendly infrastructure such as bike lanes and marked cycling routes could open up commuting to a wider audience.

Until then, there's always safety in numbers. Critical Mass, a monthly event that brings together cyclists for a mass ride through Cleveland's streets, attracts 300-plus two-wheeled revelers throughout the summer months. At the start of last month's ride, two cyclists who met through the group got married on Public Square. Following the ceremony, the bride and groom changed their outfits, hopped on their bikes and joined the ride.

"We're changing people's perceptions about biking," says Bacsa. "People see us and beep, but not because they want us to get out of the way. They're happy to see us."