is cleveland on the right path when it comes to matters of transportation?

A half-century ago, Americans staked the economic future of cities on the backs of cars. Current affairs offer a sad yet ironic take on that way of thinking: the Motor City is bankrupt and bike-friendly Minneapolis is consistently ranked among the most livable cities in the country.

Suffice it to say, City of Cleveland officials and non-profit leaders are taking notice of how an improved cycling infrastructure can reshape the future of our city for the better. How the city proceeds with a handful or projects -- good and questionable -- could push us closer to the fate of either Detroit or Minneapolis. We vote for the latter.

Butting Heads

In recent years, bike advocates often have butted heads with decision makers over transportation policies. Many argue that the city continues to support motorist-favored infrastructure such as the Horseshoe Casino Valet Center. The year-old garage added 250 new parking spaces to an area already serviced by 8,000 spaces within a three- to four-minute walk of the casino, according to a 2011 Plain Dealer article.

Approval of the Valet Center ostensibly crushed all hopes of turning Prospect Avenue into an integral cycling artery. Critics argued that the decision essentially negates recent pro-bike maneuvers, such as the opening of The Bike Rack (a cyclist commuter facility) just around the corner from the Horseshoe Valet Center. Many felt the increased car traffic from the Valet Center would be akin to sending a cyclist out onto a freeway.

“Strong and Growing”

The 14.5-foot-wide separated bike path on the north side of the Lorain-Carnegie Bridge was a concession by Ohio Department of Transportation officials who faced unhappy cyclists in light of the nearly $300 million Inner Belt Bridge project. The $4.5 million bike lane, along with sharrows that indicate cyclists may use the full north and southbound lanes, were created in large part because of advocacy from Bike Cleveland.

These recent infrastructure improvements ultimately leave Jacob VanSickle, Executive Director of Bike Cleveland, optimistic about Cleveland’s cycling future. He says there is a “strong and growing cycling culture” here backed by grassroots groups such as Crank-Set Rides and Cleveland Critical Mass. “Education and awareness programs by Bike Cleveland and the Ohio City Bicycle Co-op are really helping to raise the profile of cycling among the general public.”

Admittedly, not everybody is motivated by altruism. But even for those who are guided by the almighty dollar, there’s sufficient evidence to suggest that improved cycling infrastructure is essential to a growing economy.

Cleveland's High Line

In-the-know Clevelanders might be familiar with an ambitious project called the Red Line Greenway, which would follow alongside the RTA Red Line rapid route for three miles and through six neighborhoods. Rotary Club of Cleveland, which is championing the project, is hoping to purchase the property from RTA to develop a unique, world-class urban green space.

Leonard Stover, Project Coordinator, says it’s difficult to estimate how much money the project might generate in economic activity, but he’s quick to reference New York’s famed High Line, a $1 billion project that led to $4 billion in economic development. With regard to the proposed greenway project, Stover, a CPA by trade says, “I would be pleased with a fourfold return on our investment here, but I think it could be even better.”

The Red Line Greenway isn't the only promising local project in the works. Jenita McGowan, Chief of Sustainability for the City of Cleveland, points to the city’s commitment to “complete and green streets,” a policy that ensures that everybody can have equal access to a street regardless their mode of transportation. For the city, improving cycling infrastructure is an ongoing process.

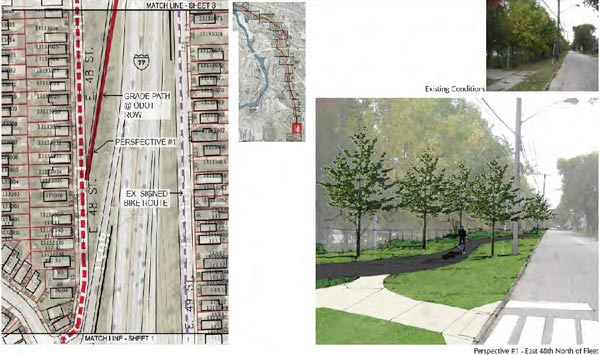

“As we resurface a road, we are implanting bicycling infrastructure at that time based on the bike plan or input from Bike Cleveland,” who is a member of the city’s Complete and Green Streets taskforce, McGowan explains. She is most excited about Fleet Avenue in Slavic Village, which will be the first fully reconstructed complete and green street since the ordinance passed. “I see that as a demonstration of the transformative potential. Fleet will have bike lanes, green infrastructure and pedestrian amenities.”

Retrofitting Cleveland

Two other projects grabbing people’s attention include a $5.6 million off-street trail for cyclists and pedestrians along W. 65th and the conversion of former streetcar medians along miles of city streets into a “bicycle expressway.” Heading up the latter project are John McGovern, a Detroit Shoreway resident involved with Ohio City Bicycle Co-op and the RTA Citizens Advisory Board, and Barb Clint, Director of Community Health & Advocacy at YMCA of Greater Cleveland.

“We envision it as an expressway because the center lane would essentially form a boulevard down the middle of the street,” McGovern explains. “This would allow cyclists to coast on their earned momentum instead of having to stop, often for no reason, at stop signs or red lights every few blocks.”

The duo says their original plan has been to complete the project by 2016, the City of Cleveland’s year for sustainable transportation. McGovern still thinks it’s possible since their proposal does not require building any new infrastructure, “but rather retrofitting existing streets with a center bicycle facility that is protected.” Clint adds that the paths would be buffered on either side by three to four feet of plantings. “It would serve as a cycling magnet,” she believes, encouraging Clevelanders who currently limit their cycling to recreational outings to become commuter cyclists.

"Opportunity" Corridor

Some might scoff at the idea of removing roadway from cars, but VanSickle says it's a natural response to the reality of Cleveland’s population loss. “Cleveland’s roads are built for well over one million people, yet our population is under 400,000,” he says. “By reclaiming much of the excess capacity to implement a network of connected, stress-free bikeways, Cleveland has the opportunity to become the cycling capital of the Midwest, if not the entire country.”

Considering that so much of Cleveland’s current (and excessive) road infrastructure is in poor condition, many cycling advocates are saddened by the Opportunity Corridor project that would extend I-490 at E. 55th all the way to E. 105th in University Circle. While the City says the roadway will comply with its Complete and Green Streets policy, and supporters say it will bring economic prosperity to the impoverished neighborhoods it bisects, not everybody is a fan.

Marc Lefkowitz, an editor at the GreenCityBlueLake Institute, is one of those firmly in the skeptical camp. He believes the $334 million allocated for the project could be better spent improving bike infrastructure and existing roads that currently connect the neighborhoods of University Circle, Central and Fairfax. “This road is $100 million a mile, the equivalent to about 90 years of maintaining and improving our existing roads,” he explains. “Why are we discussing $3 billion in new highway projects when we can't even afford to keep our existing roads in good repair? A drive down Chester Avenue is proof that we don't need a new road.”

Indeed, take a drive down any number of Cleveland’s largely uninhabited thoroughfares and you'd have to agree. Simply put, there’s no need for such wide roads given the city's current population. Not only that, it runs counter to the desires and habits of younger people -- the one demographic that actually is increasing within city limits.

“This proposal to go all in on highways is out of step as Americans are choosing to drive less,” Lefkowitz stresses. “There is a rising tide of Millennials and Boomers who are taking their foot off the gas pedal and putting it on a bike pedal.”

Examined from that angle, it really is hard to argue that Cleveland is on the right road to recovery.

“It’s about talent attraction and business attraction,” argues VanSickle. “When you look at what young people are looking for, when you look at businesses who want to hire those people, you have to create that kind of city.”

Photos Bob Perkoski except where noted