Anti-bullying project shows #CLE kids that words hurt too

Craven Smith was bullied as a child. To cope, he became a bully himself. Now he’s on a mission to prevent bullying.

“Being bullied is never a hopeless situation,” Smith tells kids. “Learning how to handle yourself will help you to handle most of the bullies you might face.”

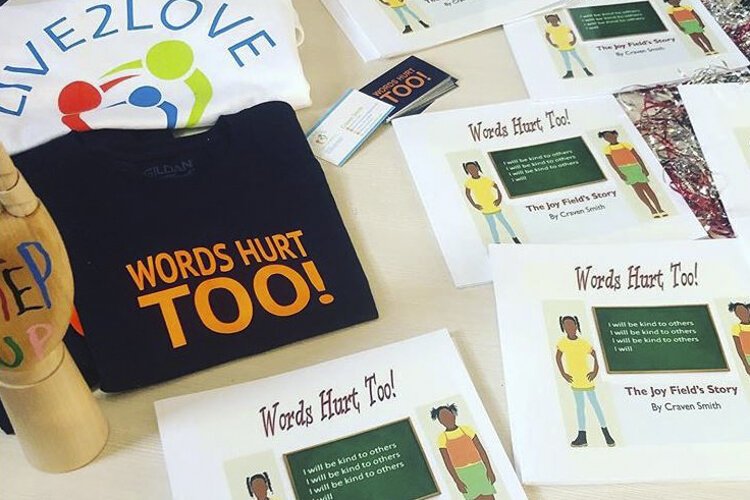

Smith's Live2Love Project grew out of this fervor. Inspired by a former classmate’s comment, Smith changed his ways. Last year, he quit his Cleveland factory job and created the nonprofit to spread his message wherever he can, conducting workshops and reading his poetry at schools, churches, libraries, festivals, even barbershops. He’s writing a series of books on bullying called “Words Hurt Too.”

“It really sparks a fire in me when I see a child getting bullied or hurt or hear a story about being bullied, or even just being a bystander,” Smith says. “All I try to do is share my story with that child and tell them I took that pain and made it into some enlightening information for someone else, and try to give kids a chance to think through ways of solving problems.”

Smith, 33, grew up on East 93rd Street in Cleveland’s Woodland Hills neighborhood. The youngest of four, he showed writing talent early on, taking after his mother, Sharon James. She enrolled him and his sister in a West Side elementary school, Newton D. Baker School of Arts. Trouble began on the bus ride across town.

“This kid who was staying a few streets from us would get on the bus with us,” Smith says. Nothing was said at the bus stop. “But once we got on the bus, he started making fun of us. ... He would call us names. And a lot of kids would laugh at it. Once we got into the school, the kids would whisper about how he talked about us, and that provoked them to make fun of us.”

Smith told his brothers. “I didn't know how to talk to my mom about it. My father was in and out of my life. So I would go to my brothers with issues. And my brother Justin, he didn't like nobody talking mess about nobody, so he would stand up for a lot of people. And I’d tell him about it. One day, he walked us to the bus stop and kind of roughed the guy up.”

The bullying stopped. “That triggered me into realizing, ‘Oh, that's what I have to do. I have to be violent.’ I took that from that situation. And I also took that, ‘Oh, I have to be the bully before I get bullied.’ So when I went to a different school, I started becoming a bully.”

Several schools expelled him for bullying, including East Tech High School. “I had to beat the bully to the punch,” he says. “I became a monster to beat a monster.”

He attended Cleveland State but didn’t graduate. “I was in and out of situations. … I was lost, I didn't know where I was going in life, until I met someone from middle school who told me some things I used to say to them and how it affected them. And I'm thinking, ‘We've grown, but you’re still holding on to that?’ … And that's what made me realize that words hurt too, and it kind of just stuck with me.”

He was 20 or 21 and ready to rethink his life. “Just by being more into the church, speaking with wiser people, and really taking the time to figure out what do I want to do in life? How do I want to leave my legacy? And how can I help people that are my peers and the next generation coming up?”

The environment he grew up in was unsafe, he says, but he appreciates his mother’s efforts. “The house was a home. She taught us things. When we’d get in trouble, we’d have to do book reports. It wasn’t a whoopin’ or stand in the corner. It was more of an understanding of information, it was knowledge. And that always stuck with me.”

Spreading the word

Now he’s sharing information on bullying. “That's my main focus, to get that information out there to these neighborhoods that I've been in and grew up around this cycle that's just repeating itself, because it's the same things.”

Communication is the key. “The main thing for them to do is understand where they are at,” he says. “So if they are getting bullied and people are watching it, then they have to tell someone. Tell an adult. Tell a trusted friend who can speak for them, and then it's not like it's just pressing the issue toward the ones getting bullied, it’s pressing it toward the ones allowing it to happen. The bystanders, the ones who laugh, the ones who don't say nothing and just walk away. Everybody has to be held accountable.”

Witnesses need to tell an adult. “Or intervene with the bully and say, ‘Hey, that's not cool.’ Or pull the person who was getting bullied to the side and kind of build their confidence, tell them it’s OK, it's cool, don't worry about it, but also to say something.”

Parents must raise the issue, he says. “When we tell our kids, ‘Don't hang with this crowd or those type of people,’ it’s the same thing. You have to sit down and talk to them. Not putting them on the spot, because maybe they’ll want to come back later and talk about it, but just give them a clear understanding that you know what bullying is.”

People need to share their experiences. “Like, ‘Oh, my dad, he's a tough guy. I've never even seen him cry, but he's been bullied,’ or ‘He helped somebody.’ And the same thing with the moms, you have to show them that you've been there before. Share your story with them.”

The book series

Smith’s first book, “Words Hurt Too: The Joy Fields Story,” is a fictional tale of someone facing bullies. Aimed at elementary school students, it’s for sale on Amazon.

His second book, “Words Hurt Too: The Game Plan,” for middle schoolers, will be published soon. Instead of chapters, it’s broken into quarters, using a sports theme, with questions and answers at the end about what to do in certain situations.

Next, he will write “Words Hurt Too: Life Recycled, Behavior Inherited.” Intended for young adults, it addresses cyberbullying. “That really affects this generation, because it's just nasty messaging, spreading rumors, posting inappropriate photos of someone or of themselves,” he says.

The Live2Love Project received a $2,500 grant from Neighborhood Connections in November. Workshops will resume after the coronavirus crisis passes.

“When I talk with children, it's not just a talk, it's a whole activity, it’s a workshop, it’s involvement. That’s what we believe changes the behavior. Because I can talk to children about bullying, and point the finger at them, and tell them how much that is not right. And it can go in one ear and out the other.”

At a recent workshop, he passed out paper plates and small tubes of toothpaste and asked the kids to squeeze all of the toothpaste onto the plate. Then he said put the toothpaste back into the tube. They couldn’t. And he explained that the toothpaste is like the words we speak: Once it’s out, it’s out, and you can’t undo it. Words hurt too.

“I’m very, very proud of him,” says Deborah Wright, owner of Parablist Publishing in Euclid, publisher of his books. “Because he came to me with a series of books … and he just took off running with it. … Not only did he get his book set up, he got his whole nonprofit set up, and he's really doing a lot of things in the community.”

Connecting with children

They belong to the same church, St. James AME in the Fairfax neighborhood. “He came to an event that I had and put on this video,” Wright says. “And it was just amazing watching the kids participate, not only learning about bullying, but he has interactive games and activities for them.”

She loves his message. “He's trying to make every person feel like they're important. And you're important enough to not allow people to bully you, and you're also important enough to to stand up for other people. If you see people bullying, kids bullying another child, there's something you can do about it.”

Smith recently moved to Cleveland Heights with his girlfriend, Shanice, where he’s a stay-at-home father to their 1-year-old son and her three young boys. During this sheltering period, he’s focusing on writing and posting on Facebook and Instagram.

When he sees people he grew up with, and they tell their children he’s an author, that also helps make a difference, he feels. “The kids are like, ‘He’s an author?’ It seems like something they’ve never heard of, something that’s out of their reach. But by me being present, by me giving them this information, by me being on this new path, I think that is changing a lot, giving them ideas that they aren't thinking about.”