game on: cleveland institute of art hits 'start' on game design program

Film critic Roger Ebert once stated that video games can never be art. Don't tell that to Knut Hybinette, a professor who teaches game design and digital foundations at Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA). His students combine technical talents and an artistic vision with a hopeful eye toward a career in the gaming trade.

CIA's game-design program teaches a plethora of skills prospective dream makers need to thrive in the virtual world. Among them are 3D modeling, animation, programming, visual design, interactive storytelling, audio and game production, plus additional coursework that examines videogame culture and digital media. Presentation skills like writing, storyboarding and direction are also part of the curriculum.

College students gravitate to video games like moths to a computer monitor. A medium that combines boundless creativity and artistic talent is a natural fit for the independent college of art and design, says Hybinette. The program officially was launched last fall as an offshoot of the school's popular Technology and Integrated Media Environment (T.I.M.E.) digital arts major, which has produced 96 graduates since Hybinette arrived in 2005.

Well-rounded students usually make the best game designers, explains Hybinette. The professor goes so far as to encourage his charges to take classes like anthropology. Knowledge about other cultures, he believes, will only help inform a student's inventiveness in a creative arena that includes everything from Flash-based apps for the iPhone to industry-changing beasts like the hugely popular first-person shooter Call of Duty.

"There are so many different types of games, and in this industry you can't just have one kind of skill," says Hybinette, a native of Sweden with a background in animation and game design. In a field with such wide boundaries, "we want our students to be able to work among all of them."

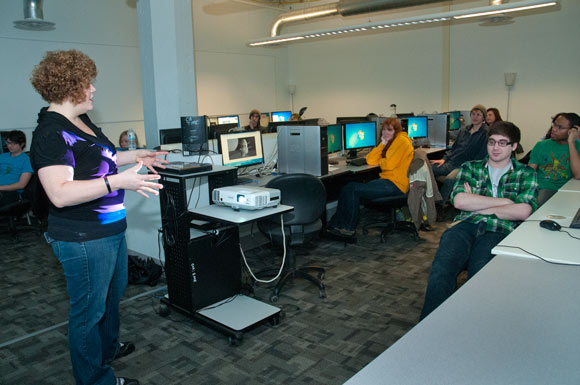

Just as multiplayer titles like the zombie shooter Left 4 Dead rely on collaboration for survival, CIA's game-design program emulates the team-oriented culture found at successful gaming companies. Game design majors take core courses with students from other majors, including Professor Amanda Almon's biomedical art program, which combines applied art, science and technology to create visual education materials on scientific and medical topics.

The brainstorming among students opens them to differing perspectives and techniques, cementing the team-building assets integral to character design and production, says Almon. Several biomedical art students who took Hybinette's gaming courses are now working on a genetics-based educational Flash game.

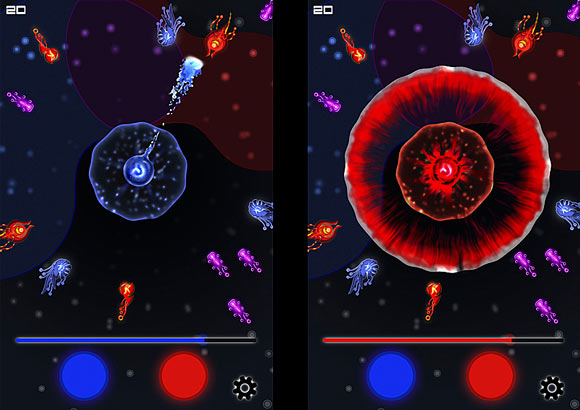

Hybinette also expects more collaborative efforts similar to the one that produced the colorful and popular smartphone game ChromaWaves in 2010.

The project was a joint effort between CIA students and a group of computer science majors from Case Western Reserve University. ChromaWaves harnesses the iPhone's touch-screen, allowing players to drag and flick swatches of pigment to fight off enemy balls of color, which explode and leave vibrant ink stains on the screen. The CWRU students mostly worked on the game's technical aspects, while CIA members concentrated on its artistic elements.

The student-designed game took a year to make. Those who wanted to be part of the team submitted portfolios as if they were applying to a real game developer. Members who did not work out or who caused conflict within the group were let go. A harsh modus operandi, Hybinette knows, but one reflective of a difficult and demanding profession.

"Failure is the greatest thing [my students] can learn," says Hybinette.

"We want to teach students to be leaders" of a creative team, adds Almon, who starting next year will lead a CIA course on "serious gaming," a designation that emphasizes "the gamifying of dry, educational concepts to make them more interesting."

Elizabeth Keegan describes herself as a "gamer at heart." The 23-year-old still holds fond memories of playing Mario Kart with family members. A graduate of CIA's digital arts school, she now is Hybinette's teaching assistant, helping with game concepts and technical programs.

Armed with illustration and graphical design prowess gleaned in high school, Keegan was the art lead for several projects, including Veggie Vengeance, a vegan-friendly side-scrolling platformer. She primarily is interested in 2D and 3D environmental design, and loves working in collaboration with large teams, an approach she would rather apply to quirky puzzle games than the next big first-person shooter.

"It's about challenging the industry," says Keegan. "Creating is cool."

CIA's game-design program currently has 20 members, mostly sophomores and juniors. Keri Svoboda, 21, has been gaming most of her life, starting with the adventure classic King's Quest, which she played on her grandmother's PC. She enjoys older games like the immersive puzzler Myst, and counts the globe-trotting Assassin's Creed action/adventure series among her current favorites.

Svoboda took a videogame level design course last semester and plans next to study character design. The level design class allowed her to work with the complex software used to build video games. While she can appreciate a frenetic sci-fi shooter like Halo, Svoboda would rather create educational science games for children.

"They can reconstruct a body with bones they find, or destroy garbage in the ocean," she says, rattling off a few ideas. "You want kids to learn while having fun. The options are limitless."

She envisions a future working for a game developer, but she's not sure where that future will be. While Svoboda's condition is not uncommon for the program's young graduates, Hybinette does see a growing Cleveland-based gaming culture to keep grads in town.

Flipline Studios, a company that makes online and downloadable titles, was founded in 2004 by CIA grads Matt Neff and Tony Solary. Two more of Hybinette's former students currently are working for Cleveland-based LACHINA, an educational design firm and creator of innovate learning apps. There's also a Cleveland Game Developers group boasting more than 250 members.

While game developers have a notoriously high burnout rate thanks to crazy hours, Hybinette doubts that killer schedule would dissuade many of his students.

"You really have to love the process," says the professor, adding that his students often have more fun making games than playing them.

Photos Bob Perkoski *except where noted

- Images 1 - 2: CIA Biomedical Art Professor Amanda Almon

- Images 3 - 7: CIA Game Design Professor Knut Hybinette and class

- Image 8: CIA gaming program grad student, Liz Keega

- Image 9: ChromaWaves game still *