Black leaders must make connections, McShepard tells City Club

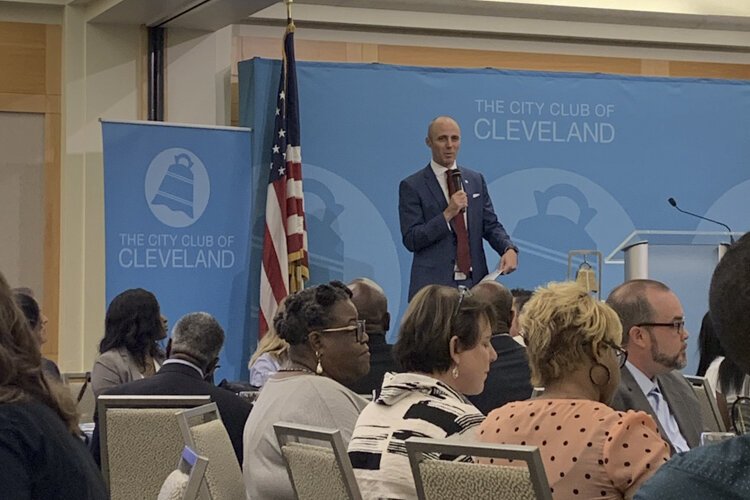

Standing before the podium in a gray pinstriped suit and purple tie, Randell McShepard cast a towering presence at the City Club of Cleveland on Friday, Aug. 16, where he spoke to a sold-out audience on the future of black leadership in Cleveland.

If McShepard’s presence was commandeering, it was only fitting for his subject matter, which summarized the key points of his report, “Missing in Action: An analysis of black leadership and the challenges that impede success and impact.”

The 16-page analysis was released in early June by Policy Bridge, an African-American-led public policy think tank for which McShepard is board chairman. A number of factors over the years inspired him to conduct the report, he says, ranging from requests for guidance from emerging black leaders, to requests from civic leaders as to the whereabouts of other black leaders.

“Whatever the case, we all know that there are myriad reasons why black leaders are not always easily identified or chosen for leadership roles, which is frankly debilitating to our city,” McShepard says. “So I concluded that someone—someone—needed to explain the challenges of black leadership, including how we got here and where we need to go. And that someone was me.”

Yet what inspired McShepard most of all was a question that has haunted him for more than a decade, often put forward by people looking to find minorities for nonprofit board seats: Where are the black leaders?

McShepard’s answer to that question, however, might seem counterintuitive: everywhere. He contends that it is not the absence of black leadership, but rather the lack of connection and discourse between black leaders across the board, that has presented a problem for leaders in the African-American community.

McShepard breaks down black leadership into four categories: civic, business, political and community. Civic leaders generally address larger scale issues, and their decisions often affect communities and neighborhoods—those behind the Opportunity Corridor project, for instance. Business leaders are entrepreneurs focused on the private sector, many of which are sole proprietors. Political leaders are the black folks running for public office, while community leaders are the ones typically portrayed by the media—"Do the Right Thing" style activists who work for social change on the ground level, often within their individual neighborhoods.

In order to improve the state of leadership in the African-American community, McShepard believes it is necessary to understand how these categories operate and complement each other; for black leaders, both emerging and established, to work together by establishing connections across the board.

"These categories are important to note because if an individual can understand each of them in depth, they will be better positioned to successfully navigate the terrain and get things done,” he says. “When young people approach me to say that they want to be a leader, I often suggest that they pick one of these categories to master as a first step, as being a leader in all four categories is rare and takes a long time."

This can happen in any number of ways. A big one is fostering relationships among a mix of leaders, approaching them from other categories and asking them for help or mentoring, for instance. Another solution is designing new outlets that give minority leaders a chance to be heard. This includes appearances on TV programs, enhanced media coverage, sponsored keynotes at nonprofits and universities, and even City Club forums.

“Minorities shouldn't have to be in protest mode to get the opportunity to speak publicly,” McShepard says.

He also suggests incorporating community leadership into high school and college curriculums, thereby teaching young people how to become emerging leaders in their communities. Finally, McShepard encourages supporting civic and community training programs aimed at minority communities.

“Courses on public policy should be taught at the neighborhood level, and racial equity institute training and community organizing workshops can help to encourage residents to monitor more closely the impact of systemic racism, neighborhood disinvestment and weak political leadership,” he says. “And, most importantly, what they can do about it."

This article is part of our "CLE Means We: Advancing Equity & Inclusion in Cleveland" dedicated series, presented in partnership with Jumpstart, Inc., Greater Cleveland Partnership/The Commission on Economic Inclusion, YWCA of Greater Cleveland, and the Fund for Our Economic Future.