if you build it: area advocates work to get cameras rolling on cleveland film industry

The trailer for Captain America: The Winter Soldier is undeniably awesome: Fiery explosions, high-speed motorcycle chases and breakneck hand-to-hand combat are always hallmarks of a good time at the local googolplex.

Even cooler are the snippets of Cleveland seen in the clip: West Shoreway, West 3rd Street, Rockwell Avenue and Superior Avenue all get their close-ups as the sub-titular Winter Soldier wreaks havoc on the streets of a stand-in Washington D.C. The would-be blockbuster shot here for six weeks last May and June, and was helmed by Clevelanders Joe and Anthony Russo.

Watching Cleveland getting rocked for two hours is great, but when the sugary rush fades, a certain reality creeps in, that being the big shots who filmed their glossy thriller in our fair city have been ensconced in Los Angeles or New York for months, and there is no guarantee they're ever going to return.

An active if nebulous group of area producers, filmmakers, nonprofit leaders and school officials want Cleveland to capitalize on the momentum gained from recent Hollywood blow-bys. They're advocating for an infrastructure comprised of highly-trained technicians, brick-and-mortar filming space and friendly tax credits that would attract more film projects, or even a prestige television drama that would use the North Coast as a backdrop. Fresh Water talked to a handful of these Cleveland believers working to energize the local film scene.

Build it up to bring it home

When producer Tyler Davidson is planning a new movie project, he always thinks of Cleveland first. This is not lip service spoken from the airy heights of Hollywood Hills -- when not on location, Davidson does his business from an office in his native Chagrin Falls.

Davidson, 39, has produced seven features, the last four of which have appeared at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. Two of his movies, Take Shelter and The Kings of Summer, were shot locally. Parts of the coming-of-age tale Kings of Summer were filmed not far from Davidson's home in the bountiful wooded areas of the Chagrin Valley.

After five years learning the industry in Los Angeles, Davidson appreciates Northeast Ohio's slower pace. There's also a level of comfort in knowing the caliber of locations and filmmaking personnel here.

"There's excitement about the business in Cleveland you just don't get in New York or L.A.," says Davidson. "People [elsewhere] get so inundated with the industry they become jaded."

The area already had the diverse settings and robust architecture that appeal to creative types, notes Davidson. It now also has the powerful backing of advocacy groups like the Greater Cleveland Film Commission, which supports the creation of a comprehensive film industry within the region.

Film commission president Ivan Schwarz has been lobbying for a higher cap on the allotment of the incentive that the state offers to filmmakers who bring their ventures to Northeast Ohio. More movies mean more money flowing into the area, which could eventually lead to the construction of a permanent studio soundstage or post-production facility, Davidson says.

Creating an infrastructure is the next logical step for our embryonic film industry, he says. Davidson would like to see Ohio emulate Louisiana, which offers an attractive 30 percent tax credit on a movie's production budget. While a filmmaker may prefer to stay in Los Angeles for a long shoot, a deal like Louisiana's, put simply, is too good to pass up.

"We need to organize and make a collective decision that, yes, we're going to build an infrastructure here," Davidson says. "As much as Northeast Ohio has to offer, filmmakers are standing by to see if we can cement a stable industry."

It's made out of people

A solid infrastructure needs people at its foundation, say leaders of a pair of university-based programs aimed at teaching students the technical side of movie making.

Cuyahoga Community College (Tri-C), with backing from Cleveland's film commission and the local film and television industry union, is offering a film crew technical training program. The three-week program launched in January, teaching classes in cameras, lighting, sound, special effects, stunt work and the intricacies of being a production assistant. Students receive certification following the course, which is taught by local film industry instructors.

"Students are working with film equipment and gear they'd see on set," says instructor Simone Barros, whose experience includes production work on Comedy Central's Chappelle's Show. "We've got a camera class that's seeing a camera be built from scratch."

Hands-on on work can lead to entry-level opportunities in entertainment production, says curriculum director Lee Will. While she understands her current grads might have to leave town to find employment, the idea is to build a capable crew base within the region.

"The lack of that core has been a big obstacle for more movies coming to Cleveland," Will explains. "This program is an answer to the challenge of shooting here."

A dedicated foundation of skilled crew members can build Northeast Ohio's portfolio as it competes against other burgeoning film communities in the South and Midwest.

"We'd love to have a TV series made here," says Barros. "If we're determined and tenacious, we can build an industry."

There is far less distinction between television and film than there used to be, notes Evan Lieberman, director of Cleveland State University's media arts and technology division. HBO's sumptuous serial killer drama True Detective, for example, displayed star power and a high-gloss style that would have been at home in any first-run movie.

To that end, CSU's film and digital media major integrates film studies with production. A two-course sequence includes screenwriting, cinematography, editing and other aspects of filmmaking, and concludes with each student making his or her own short narrative film. With this skill set in tow, graduates could find themselves on the set of a documentary, reality TV program or guns-a-blazin' action flick.

"The lines are blurred with so many projects using the same principles," says Lieberman. "We're trying to create an immersive, well-rounded experience."

Engaging young people with "The Big, Amazing Movie Set" that is Cleveland is the next challenge, says the department director. Most of Lieberman's students leave for graduate school or for entry-level positions on out-of-town productions. Nor does Northeast Ohio have much in the way of post-production facilities.

"The talent is here but much of the power is elsewhere," he says. "Right now this market supports the one-man-band approach, where a single person is the writer, producer and director."

A vision of the future

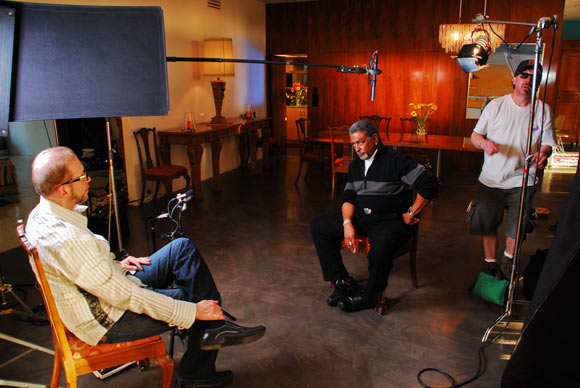

Documentarian Todd Kwait would love to pull crew members from Cleveland for each new project. The Shaker Heights resident has been producing movies on music for nine years. His latest, Tom Rush: No Regrets, studies the influence the folk musician had on generations of artists.

Trained as a lawyer, Kwait, 54, describes himself as a "non-trained movie scholar" with a specific interest in motion picture history. He delved into the medium himself in 2006 with the jug band documentary Chasin' Gus' Ghost, a venture which began with a letter to Lovin' Spoonful's John Sebastian. Kwait heard back from Sebastian and soon the pair were sitting down to discuss the details.

"I had never done film, and had no connection with the entertainment business," says Kwait. "I gave it a shot, anyway."

Now working on his fifth music-centric documentary, Kwait wants other blossoming Cleveland auteurs to harness the resources a sustainable film enclave would bring.

"The community we have now is very active and tenacious," Kwait says. "But how can we make Cleveland a place to work every day on movies and TV shows?"

While robust, the market here still is in its infancy, notes producer Davidson. Still, mining from local crews and filming on an honest-to-goodness soundstage downtown are among his silver-screen dreams.

"I want to make movies here because this is where I want to live," Davidson says.