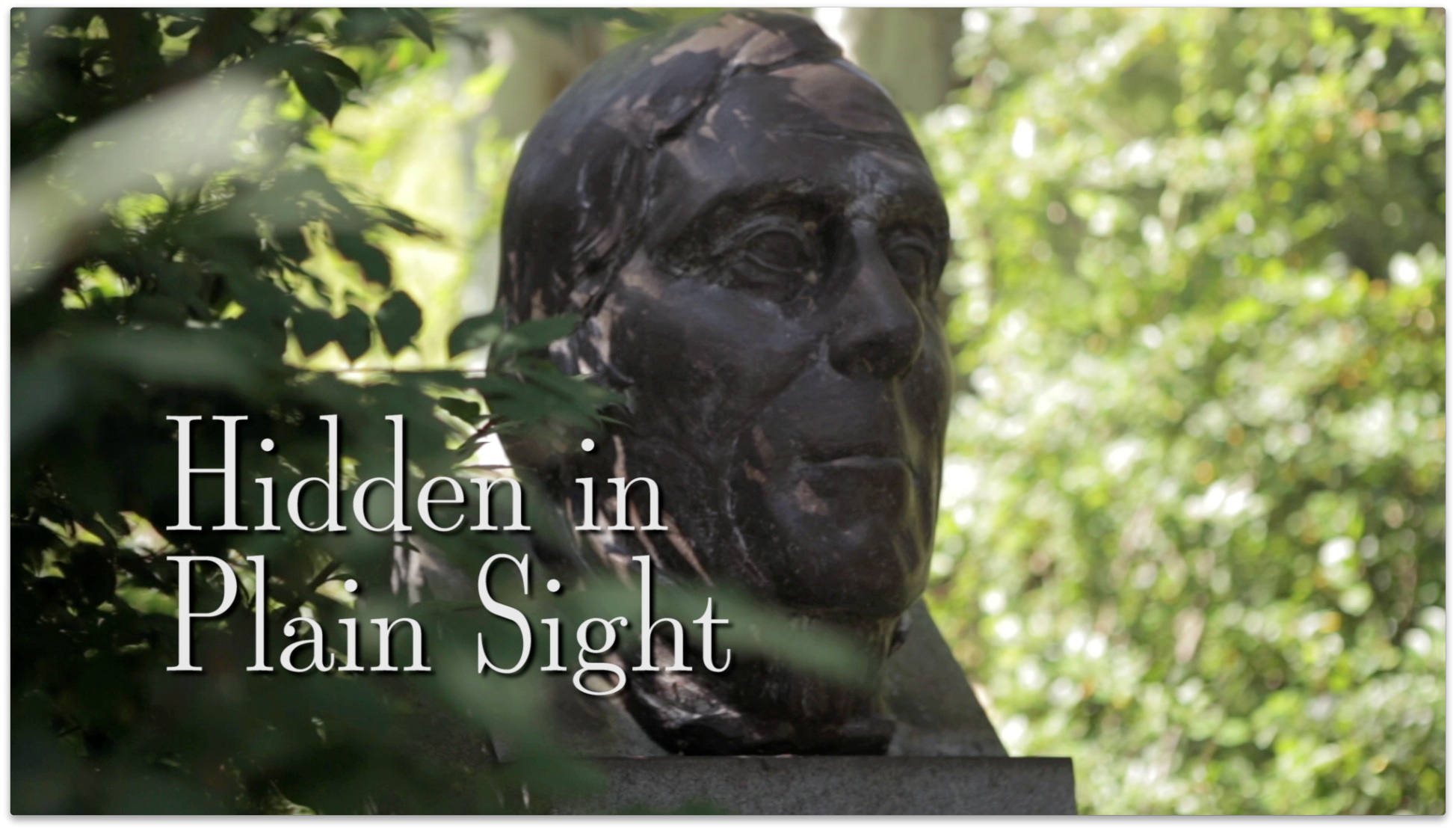

The Cleveland Cultural Gardens: Hidden in plain sight

Editor's note: The documentary short Hidden in Plain Sight, written and produced by Luke Frazier, will be screening on Thursday 3/18 at 8:50 pm, Saturday 3/21 at 7:15 pm and Monday 3/23 at 5 pm at the Cleveland International Film Festival at Tower City Cinemas. Saturday & Sunday the film precedes the full length movie Kilbanetown Comeback. On Sunday 3/22 at 7:30 pm it will screen at the Capital Theater on W. 65th Street, again preceding Kilbanetown Comeback.

The thing about the Cleveland Cultural Gardens is that they are gardens, sure, but that’s really not the deal.

I love the Gardens for all kinds of reasons; they’re like my favorite secret place, but in plain sight, a couple of winding miles, old tree slopes, busts of cultural heroes, statues caught in mid-speech.

Thirty plus gardens and still growing, a fanciful blend of earnest ethnic attitudes and syrupy sentiment.

Dubbed the world’s first peace garden, they were created by nation-lovers during the waves and waves of last century’s “All Aboard for America” migrations.

Shakespeare’s garden came first in 1916, then dozens of countries in the next two decades and on up to now…planting themselves with intentions, determined to show the world that the people who paid and made these Gardens came from places of taste, of higher ideals, of peace...despite histories that included brutal wars.

From places that spawned scientific knowledge, humanitarian courage, wit and wisdom. Being proud to display and share, claiming at least partial ownership to universal goods...no matter how hokey-pokey that sounds now, or maybe even sounded back then.

The Cleveland Cultural Gardens became the attraction, with Rockefeller’s donated land the growing canvas for Hungarians, Slovaks, Poles, Germans, Irish, Greeks, Italians—the original desperadoes, the opportunity seekers fleeing the old for the new.

More recently it’s the Indians, Albanians, Azerbaijanis, Syrians, Croatians and on and on, all combined to converge on this particular latitude and longitude, just south of Lake Erie, tailing to the VA Hospital and Art Museum, themselves monuments to glorified wars and past masters.

Many of the Gardens tuck up against urban distress, or the occasionally stinky Doan Brook.

And that’s part of what else I cherish about the gardens: the unexpectedness. So many people tell me, if they even know of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens, that they have driven by and haven’t stopped.

Yeah: it's tough to pull over. They're seemingly disorganized in presentation. You aren’t looking for them so they blur in your taillights. Tossed aside with thoughts of going back one day.

But for me I do go back, many days, riding bikes with son Noah, stopping here and there to look at Gandhi or Dante, Madame Curie, some guy named Masryk, stern looking Germans, different shapes and sizes of ideas and desires, fountains either filled or not, less frequently taking in monuments of abstract inspiration. We walk among the weighty feelings of national pride in the age of a borderless web-based world.

When you visit the Gardens it’s tempting to contrast the prominently displayed white-hot language of universal brotherhood with the cold reality of messy world politics. The Gardens try to sing in one voice, but power-mad humans take it way off key.

Irrespective of any cynical rain, these gardens bloom every year, testaments to something about better natures, reminders of alternatives to destruction. To me part of the Garden’s exquisite nature is that it tries to be the kind of world we say we want -- growing closer instead of running scared.

Dedicated folks shine an occasional bright light on the Gardens, whether by festival or proclamation. Does the bright light last? Not much, it seems, but it will never be extinguished. I know the gardens will remain tight to my heart; I even ended up getting married there.

I choose to affirm the truth of the Garden’s sights and smells, ears open, eyes forward -- one world. Because the Cleveland Cultural Gardens, to a zealot like me, is a place made of magic and wonder. That’s the deal.