Metroparks, partners quietly exalt and nurture the fragile Cuyahoga

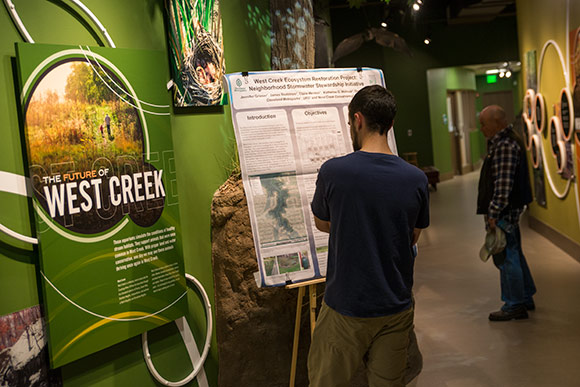

Tucked away in Parma in the heart of the West Creek Reservation sits a beautiful and living facility that will fill even the most jaded visitor with wonder. Its name, however, evokes images of test tubes filled with murky water, dull data sheets and scientists donning lab coats and thick glasses. The reality at the Watershed Stewardship Center is the exact opposite.

Treating rainfall the way Mother Nature intended

The first and most striking thing you see at the center is a living green roof atop the front portico. Beneath it, a pond gurgles under a delicate web of water lilies. Rain gardens bloom all around. Grasses dot wetlands in an area that was formerly strewn with piles of construction debris. And it all goes to serve one lofty purpose.

"Every drop of water that hits this building and this parking lot goes through a storm water practice," says the West Creek Conservancy's (WCC) executive director Derek Schafer. "Whether it goes through a rain chain, rain garden, bio swale, wetland … it gets uber-treated before it goes into West Creek."

Opened in 2013, this unique public/private collaboration between the Cleveland Metroparks, the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District and the WCC is home to no less than 62 examples of applied storm water treatment practice, all of which collect rainwater and guide it through a natural slow path back to West Creek.

For the layman, form can top function here. Glittering rain cups drip from the roof of the facility, replacing downspouts and slowing runoff water before it reaches a series of bio swales on its journey to the wetlands. Such installations inspire visitors: I could do that at my house. The median of the parking lot is a depressed rain garden that catches and slows water instead of just dumping it into a storm sewer. The concept seems so simple when it is before you: why aren't we doing this elsewhere? The living roof of sedum and succulents becomes more beautiful the closer you get to it. Even mundane components inspire. Concrete patios, for instance, are constructed from porous materials.

While the center's thoughtful construction directly benefits the West Creek, its application goes far beyond the 14 square miles that make up the creek's watershed area.

"We need to replicate this in every sub-watershed associated with the Cuyahoga," says Schafer. "It's pivotal that we not just do this in West Creek."

Jennifer Grieser conducts "Ins & Outs of Rain Garden Function" at the Stewardship Center

Jennifer Grieser conducts "Ins & Outs of Rain Garden Function" at the Stewardship Center

To that end, the center serves as an epicenter of training, development and living examples. Local and national representatives from other storm water utilities, the EPA, municipalities and grantors visit the center. Community groups and schools come as well to enjoy custom programs ranging from "Stormwater and Sustainable Development" to "From Dirt to Dinner." For the 50,000 locals who visit each year, there are a number of educational as well as volunteer opportunities.

What's the best time to visit the facility?

"The best time to see the center is when it's pouring rain," says Schafer. "You can watch all this stuff just fill up."

Confronting a lingering history

Northeast Ohioans are notorious for taking our most valuable resource, our lake and waterways, for granted. With each passing year, memories of the river that burned -- the Cuyahoga -- get further and further away. To bring the 1969 event and the state of the river back then into keen focus, just take a look at this photo from the Plain Dealer archives. That's reporter Richard Ellers after he dipped his hand into the Cuyahoga back in the 1960s. Positively jarring, but that's the way it was.

Today, however, we kayak and paddleboard upon water that glimmers beneath the dazzling autumn sunshine. We sip chardonnay on the deck of Merwin's Wharf while basking in the majestic beauty of a passing ore boat. We jog through the Scranton Flats, the gentle ducks gliding by. The state of our river, however, is not nearly as pristine as it may seem.

"The Area of Concern essentially starts just downstream of Akron," says Jennifer Grieser, the Metroparks' senior natural resources area manager for urban watersheds. "It’s the lower 46.5 miles of the Cuyahoga River. It's not just Cuyahoga's main stem, but also all the tributaries that flow into it."

photo Bob Perkoski

photo Bob Perkoski

The "Area of Concern" designation is not Grieser's subjective opinion; technical qualifications for being labeled as such were established as part of a 1987 agreement with Canada known as the Great Lakes Water Quality Act. The 43 existing Areas of Concern impacting the Great Lakes (including the Cuyahoga watershed, which is significant as it flows into Lake Erie) are not quite up to snuff when it comes to servicing all the life that depends upon them. That includes animals, plants, insects and humans.

"They call them 'beneficial use impairments,'" says Grieser, noting that one of the major indications is reduced populations of native bass, chubs and suckers as well as the aquatic insects they eat and the plants that make up their habitat. Limited diversity of species is another symptom of unhealthy waterways and riparian areas.

As local fisherman know, there are sobering guidelines regarding how much fish caught from the Cuyahoga is safe for human consumption: one meal of sunfish per week and just one of steelhead trout per month.

Fortunately, it's not all bad news. After all, we've gone from that hellish PD archive photo to those paddleboards courtesy in part of a largely unsung team that fights the good fight with slow, methodical efforts measured in tiny victories. Among them are a rain garden project along two residential streets in Parma, a reclaimed confluence in Independence and a new wetland to aid treatment of effluent to Big Creek.

What's next?

"Our largest initiative is at Acacia Reservation in Lyndhurst," says Grieser. "We received four different grants to do 1,500 feet of stream restoration and 10 acres of wetland creation." The project is slated to break ground in fall 2016 with a June 2017 completion date.

Until then, Cleveland residents can do their part by getting a free rain barrel installed. And everyone can be more thoughtful in daily practices. Grieser recommends reducing the application of lawn chemicals, choosing more environmentally friendly lawn products, opting for native plants when landscaping and taking your car to the car wash instead of washing it in the drive. For those who don't own a home or car, she suggests supporting pertinent initiatives and writing to elected officials.

"That’s really how we're making the bulk of our progress," she says.

The long game

"That was a bad day," recalls Frank Greenland, director of watershed programs at the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District, of the infamous 1969 Cuyahoga River fire, "but that fire helped spark a movement. They created the Clean Water Act. They created the EPA."

Having been with NEORSD since 1988, Greenland has been paying attention to storm water for nearly three decades and has seen significant changes courtesy of more than $4 billion in improvements to sewer systems, treatment plants and attention to storm runoff. The payoff is significant.

"I think since the 1970's, the gain has been fairly dramatic," he says. "There's been a lot of attention to the river as an Area of Concern and the recovery of the Cuyahoga. I think it’s a national success."

He adds that those gains have been somewhat offset by the general pattern of pollution and development in Northeast Ohio, citing, for instance the disappearance of farmland from the southern part of Cuyahoga County.

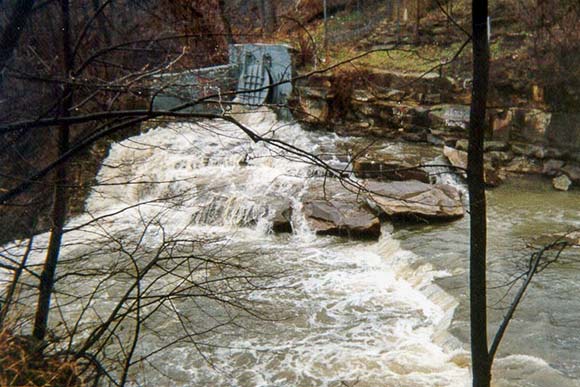

"As we've changed the landscape, storm water that used to fall onto vegetation and trickle in—infiltrate—the soil and slow down before it hit a stream now hits lots of impervious surfaces," he says.

Mother Nature's plan also cleaned and filtered the water before returning it naturally to streams and rivers. Now, huge storm sewer systems amp up the velocity and circumvent the filtering process altogether, sending fast and furious water back into streams.

Rain garden project along Park Haven Dr in Parma

Rain garden project along Park Haven Dr in Parma

"Streams weren't sized to handle that volume. They erode. They cut down. They flood with much more frequency," says Greenland, adding that the increased flow is tough on the fish and bugs and also disruptive to sediment. "We see a negative impact."

How much impervious surface are we talking about?

Per Derek Schafer, in the 14 square miles that make up the West Creek watershed alone, 37 percent of the land is covered with impervious surface. For the 39 square miles surrounding the Big Creek watershed, (both are part of the larger Cuyahoga watershed) the figure is 39 percent. Schafer adds that those numbers are pretty standard for much of the entire Cuyahoga watershed. They imply damaging levels of impact, with poor water quality and erosion.

"We are all part of the problem," says Greenland. "Everyone has storm water coming off their property," he says, emphasizing the points Jennifer Grieser put forth regarding lawn chemicals and residential runoff.

Despite that difficult reality, Greenland also notes the Metroparks' Emerald Necklace as a gentle giant in the realm of Northeast Ohio's environmental heroes. Not only does it serve as a recreational green space for residents, it also protects vast acres of riparian area and floodplain, the importance of which is often lost on the layman.

"When you have a flooding problem the most convenient solution is to build a bigger pipe and just move it to someone else. You end up paying twice. We can't do that," says Greenland.

"If we're going to make a dent in water quality," adds Schafer, "We have to have a patchwork system, a comprehensive system." He tags preservation of existing green space, the reclamation of unsustainably developed lands, the restoration of wetlands/riparian areas and retrofitted storm water practices.

"We've got to do the right things," adds Greenland.