thinking outside the box is easy at multi-million dollar invention center think[box]

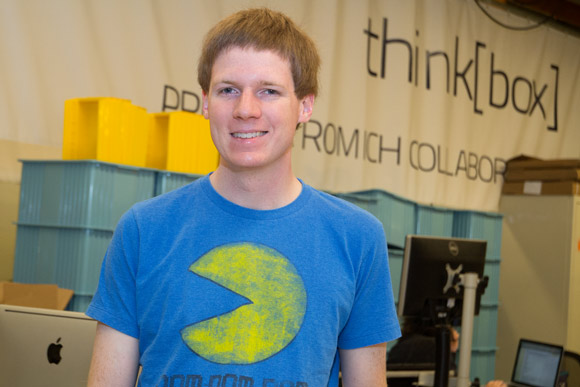

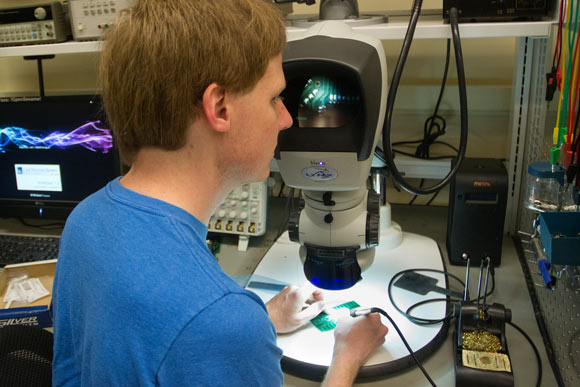

When Jonny Hall, co-founder of the Cleveland-based electronics design firm Osmisys, needed to finish up a prototype for a client recently, he headed over to think[box] on the campus of Case Western Reserve University. Thanks to the equipment Hall was able to use there, his prototype was good to go in a day or two.

“Having access to that machinery means a lot to a small company like mine,” says Hall, who graduated from Case in 2009 and, unlike many of his classmates who headed to the West Coast, opted to stay in town.

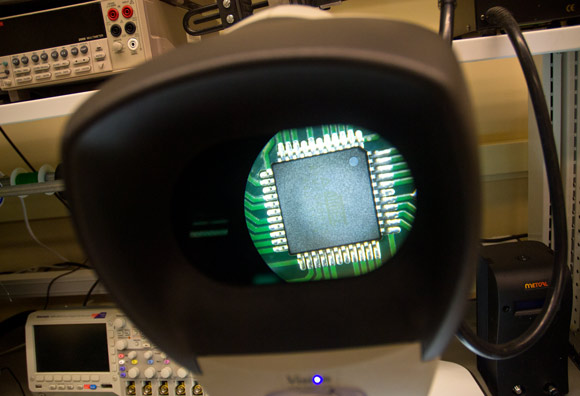

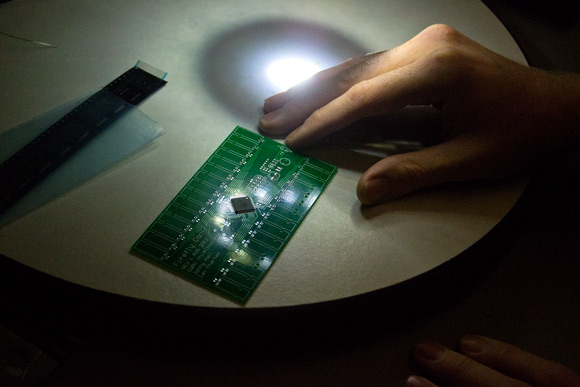

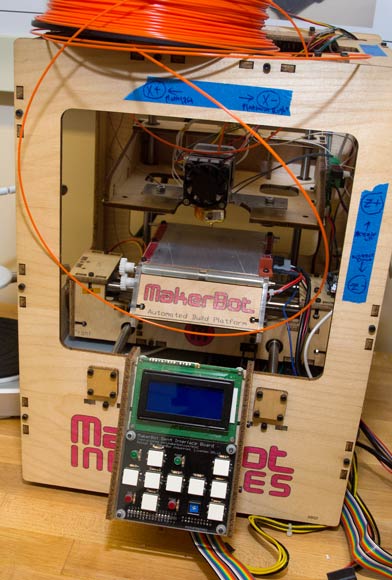

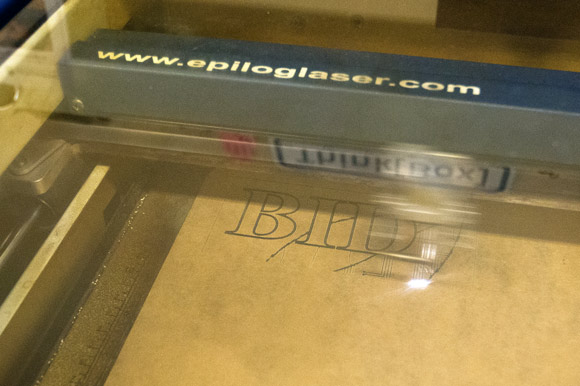

Think[box], which opened its doors earlier this year, is Case's new multi-million dollar invention center. It’s packed with $500,000 of high-end fabrication machinery that makes inventors like Hall rub their hands with glee. That includes gizmos with sci-fi sounding names like the Fortus 250mc, Epilog Helix 24, and the LPKF S63. That equipment -- a 3D printer, laser cutter and circuit board printer -- is not the kind of gear students (heck, even companies) typically have access to.

It’s all designed to be a one-stop invention space for Case students, faculty and staff -- as well as the general public.

“Our door is wide open,” stresses Ian Charnas, think[box] operations manager.

That’s great news for Cleveland’s entrepreneurs, some of whom like Hall have used think[box] to rapidly develop prototypes to present to clients and investors.

“It’s an unbelievable resource,” adds Dar Caldwell, director of entrepreneurship at the Shaker Heights-based business accelerator LaunchHouse.

Art Geigel and Christopher Armenio, who together run the Cleveland-area start-up iOTOS -- which is developing technology to control all the devices in our homes and offices with a one-stop app -- couldn’t agree more.

“This is something Cleveland has not seen,” says Geigel. “It’s going to be epic.”

For now, think[box] is housed in a temporary 3,000-square-foot space in the basement of the Glennan Building on the Case campus. But once the University reaches its goal of $25 million (it’s more than halfway there), it plans to renovate a seven-story, 50,000-square-foot campus building -- formerly known as Lincoln Storage -- into the permanent home for the center, which will boast upwards of $5 million in equipment.

When that day arrives, Case Western will boast one of largest university-based invention centers in the world, bigger even than Stanford University’s d. school, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Fab Lab, or Rice University’s Design Kitchen. It’s a venture that has the potential to play a major role in spurring innovation in the region.

“We’re hoping this will be a beacon to get smart people to Case and Cleveland and keep them here,” says Charnas, who graduated from Case in 2005 with a degree in mechanical and computer engineering. “We’d like it to be a boon not only for the University, but also the area.”

Indeed, look at regions where innovation is happening in a big way and chances are there’s a university at work behind the scenes.

“They get the wheel turning,” explains LaunchHouse’s Caldwell. “They help support innovation and create the talent pool.”

Consider Pittsburgh. That former steel town has become a high-tech boomtown, with tens of thousands of people employed by the 1,600-and-counting technology companies now operating there. Much of the kudos go to Carnegie Mellon, which over the past 30 or so years has transformed itself into one of the top computer science and robotics centers in the world. That’s helped lure investors and big-name employers to the city. Google, Disney Research, Intel, even Apple Computer staff offices there -- and there are hundreds of start-ups in the city as well, many thanks to technology first developed at Carnegie Mellon.

It’s a role that Caldwell and others say Case can play for Cleveland.

Of course, helping drive innovation in the region is not just about buying lots of expensive equipment; it’s about inspiring -- and training -- the next generation of innovators. And at the end of the day, this is a raison d’etre for think[box].

“Our dean has been pushing hands-on learning,” explains Charnas. “In the past, we held students off for one or two years. You’d have to take calculus, physics, thermodynamics, fundamentals of circuits and some other courses before you could ever make something.”

But that led to high attrition rates.

“Now we want to get our students addicted to making stuff on their first day,” he adds.

This year, at least nineteen of the University’s freshman classes -- potentially a few hundred 17 and 18 year olds -- will be using think[box] from day one. It’s this kind of tinkering that Barry Romich, a Case graduate and co-founder of the Wooster, Ohio-based Prentke Romich Company, credits for his entrepreneurial success. Earlier this year, Romich donated $1 million to think[box].

“I grew up on a farm," says Romich. "My dad was a creative guy. He still is. He probably would have been an engineer if he had had the opportunity to get an education. So I grew up with this idea of making things.”

When Romich arrived at Case in the mid-1960s, he discovered the “student shop” and spent many happy hours there. It’s an experience that afforded him the skills he needed to launch Prentke Romich -- now a global leader in assistive communications devices -- in 1966 with partner Edwin Prentke.

And it’s not just for engineering students.

“Any student can just come in and use the facility," says Romich. "That’s pretty much how the shop was.”

In fact, to date, many of the projects to come out of think[box] have been the result of collaborations among people working in a variety of fields. Take Hall of Osmisys, who worked with a student in fiber material studies at the Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA) on a prototype for “self-assembling robots” that could gather into different shapes, like an article of clothing.

Hall, Charnas and CIA industrial design student Bernadette Marconi recently used think[box] to create more than 500 motion-activated glowing fireflies that were installed in Toby Park for the dedication party Case threw last month for the new Uptown development.

This spirit of collaboration, a driver of innovation, is more than encouraged at think[box].

“We feel strongly that people should not be locked away in separate rooms, not in cubicles, just open areas where information sharing can happen on the floor,” says Charnas, who also is a founder of Cleveland’s Tesla Orchestra.

Charnas, Romich and others at Case’s School of Engineering are betting that this kind of environment, combined with all that hands-on experience, will help build the next generation of innovators. And they have reason to be optimistic. Last year, Joseph Bashover spent plenty of time at think[box] working on his senior project: an animatronic head for a robot named “Philos.”

“We could go to town with it,” says Bashover, who graduated in May. “We had access to such great stuff. We were able to make all the pieces we needed and just assemble them afterwards.”

Now working as an engineer in the area, Bashover still stops in at think[box] to play around.

“I like having side projects,” he says.

And who knows, one of those projects may be Cleveland’s next big thing.

Photos Bob Perkoski

Robot Image courtesy of Joseph Bashover

Photo of Barry Romich with JB Richey and Mal Mixon courtesy of Barry Romich