Bridging the gap: How to connect downtown and the lakefront

The Green Ribbon Coalition, a grassroots group that advocates for a continuous ribbon of green along the Lake Erie and Cuyahoga River waterfronts, will host a panel discussion Tuesday, Aug. 27, at 8 a.m., at Merwin's Wharf. “Harbor Face-off: Iconic Footbridge vs. the Landbridge” will feature proponents for competing proposals to connect the harbor to downtown. The pros and cons of each approach will be discussed.

What is the best way to connect downtown Cleveland to the lakefront? Choosing the right path is a crucial decision for the city, with long-term consequences, says Dick Clough, a community activist who serves as executive board chairman of the Green Ribbon Coalition.

“The harbor is currently ‘walled-off’ by the railroad and Shoreway to downtown Cleveland,” he says. “Creating the best possible connection between the city center and the harbor attractions is the top lakefront development priority.”

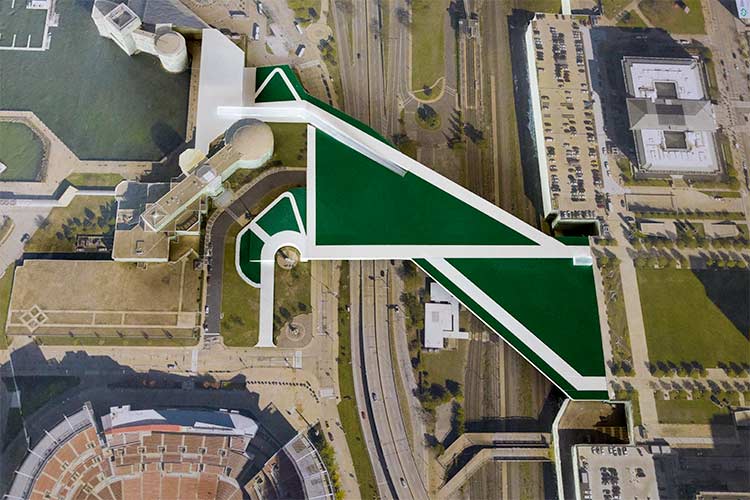

Downtown lakefront landbridge rendering.For the past century, Cleveland has wrestled with finding safer, more attractive ways to traverse the 50-foot drop in elevation and gray river of railroad lines, freeway lanes and parking lots in order to connect its downtown business and entertainment districts to the lakefront. Pedestrians have only two options, West Third and East Ninth streets, requiring them to cross intersections with busy freeway entrance and exit ramps.

Downtown lakefront landbridge rendering.For the past century, Cleveland has wrestled with finding safer, more attractive ways to traverse the 50-foot drop in elevation and gray river of railroad lines, freeway lanes and parking lots in order to connect its downtown business and entertainment districts to the lakefront. Pedestrians have only two options, West Third and East Ninth streets, requiring them to cross intersections with busy freeway entrance and exit ramps.

Representing one solution, Bob Gardin, vice board chairman of lakefront projects for the coalition, has developed a proposal to construct a landbridge over the railroad tracks and Route 2 Shoreway lanes. Seeking a feasible alternative, he based his proposal on previous designs and his involvement with the Cleveland Waterfront Coalition, beginning in the mid-1980s.

Essentially, his design creates a Mall D that would start at the end of Mall C, extend the western mall promenade approximately 90 feet and then canter it to the east, making an eastern promenade that aligns with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum and the Great Lakes Science Center’s wind turbine. The design includes an enclosed walkway that extends from the ballroom level of the Cleveland Convention Center, crosses over the rail lines and freeway and then descends to a connector building between the two attractions. An elevator would allow people of all abilities to reach the enclosed connector walkway.

“The main objective is to build a structure that extends the mall itself with roughly the same width as the existing Mall, but not so wide that you have additional costs that make it unfeasible,” says Gardin, who also serves as executive director of Big Creek Connects. “So our design extends the Mall and the main promenades and lands in the area that most people want to end up as a destination between the Rock Hall and the Science Center.”

One of the benefits, Gardin says, is that the new mall’s width of a few hundred feet provides ample opportunities for public art or sculpture parks, landscaping, places to sit, concert venues, and space for exhibits related to the Cleveland Browns and FirstEnergy Stadium, the Rock Hall and Science Center.

The primary concern with this approach is the potential cost. Considering similar projects in other cities, Gardin cites Philadelphia. Its project to connect the city’s central business district to the waterfront cost $200 million. However, that landbridge is significantly larger than Cleveland would require, and Gardin says it could be built in the $70 million to $100 million range. Further feasibility studies and cost estimates would be required before any decisions are made. Federal Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery grants are available, and public and private funding would be needed, he says.

Although he says the landbridge solution is attractive and knows this is not the first time a Mall D connection to the lakefront has been considered, Anthony “Tony” Coyne, chairman of the Group Plan Commission, says it would end up being a $200 million project. “I don’t know where you would even start on something of that scale,” he says. “I haven’t heard anybody give me an inkling that that is financially feasible, either.”

Additionally, Coyne says the landbridge would obstruct views from the large, northern-facing windows in the ballroom area of the Convention Center. Gardin counters that the “minor loss of view” would be compensated by the enclosed walkway, and the structure could allow more light to the convention center windows by incorporating an open or glass-covered area on the landbridge above the windows.

Lakefront pedestrian bridge designed by Boston architect Miguel Rosales.The solution Coyne favors is known as the Iconic Bridge, a pedestrian cable-stayed footbridge designed by Boston architect Miguel Rosales in 2014. It would provide a safe crossing pathway from Mall C over the railroad tracks and Shoreway to the North Coast Harbor. Late last year, Freddy Collier, Cleveland’s planning director, announced that the city is “moving away” from that option.

Lakefront pedestrian bridge designed by Boston architect Miguel Rosales.The solution Coyne favors is known as the Iconic Bridge, a pedestrian cable-stayed footbridge designed by Boston architect Miguel Rosales in 2014. It would provide a safe crossing pathway from Mall C over the railroad tracks and Shoreway to the North Coast Harbor. Late last year, Freddy Collier, Cleveland’s planning director, announced that the city is “moving away” from that option.

The Iconic Bridge was first offered as a solution as part of the Group Plan Commission’s three-part project to enhance the downtown area for the Republican National Convention in 2016. The plan included revitalizing Public Square, improving the Mall to be “more conducive to the community’s use for outdoor events,” according to Coyne, and better connecting the city to Lake Erie. Teamed with the Greater Cleveland Partnership, the Downtown Cleveland Alliance, Land Studio and a group of downtown stakeholders, the commission raised the funding for all three endeavors, but only the first two were completed.

Although the city and Cuyahoga County each pledged $10 million and the state of Ohio another $5 million, the bridge proposal ended up going over budget, according to Coyne. In 2015, the city and county delayed the project when cost estimates hit $33 million. While the bridge design is complete, the decision to proceed remains on hold.

“We’ve raised probably two thirds of the dollars for the footbridge,” says Coyne, who is looking forward to discussing all of these issues with the panel. “So we’re evaluating a potential redesign of the bridge that would be both iconic but also include some development opportunities halfway across on some property that the city owns.”

Another panelist, Christian Lynn, PLA, ASLA, associate principal, Planning & Landscape Architecture Practice Lead, AECOM, Cleveland, says, “We need to look at these solutions holistically, because there are a number of other problems that need to be solved. Route 2, for example, is just as much an impediment to other places along the waterfront, so it needs to be looked at with a widened scope to analyze the whole segment between West Third all the way to Dead Man’s Curve.”

In 2013-14, Lynn was heavily involved in the development of a different proposal to build a pedestrian bridge and intermodal transportation station roughly where the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority waterfront rapid station is located. He sees this as a huge opportunity to help Cleveland connect to its waterfront, as other cities such as Boston, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and San Francisco have already done.

“If we do the landbridge, yes, we solve downtown access to those particular areas,” he concludes, adding that a new master plan should be developed for the entire lakefront. “We have other ambitions for the future of the lakefront, so if we focus all of our efforts solely on the landbridge, we’re forgetting about the rest of our waterfront.”

Steven Rugare, associate professor, Architecture Program and associate of the Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative College of Architecture and Environmental Design, Kent State University, will round out the panel.

About the Author: Christopher Johnston

Christopher Johnston has published more than 3,000 articles in publications such as American Theatre, Christian Science Monitor, Credit.com, History Magazine, The Plain Dealer, Progressive Architecture, Scientific American and Time.com. He was a stringer for The New York Times for eight years. He served as a contributing editor for Inside Business for more than six years, and he was a contributing editor for Cleveland Enterprise for more than ten years. He teaches playwriting and creative nonfiction workshops at