east boulevard is a hidden gem among cleveland neighborhoods

If you’ve lived in Cleveland for any length of time, chances are you’ve driven Martin Luther King Boulevard between Interstate 90 and University Circle. Every day, about 26,000 people do, on their way to and from the Circle’s huge employers or its stalwart cultural institutions.

You’ve also probably gawked at the two dozen or so cultural gardens that dot Rockefeller Park, especially eye-catching in spring, when the flowers are in full bloom.

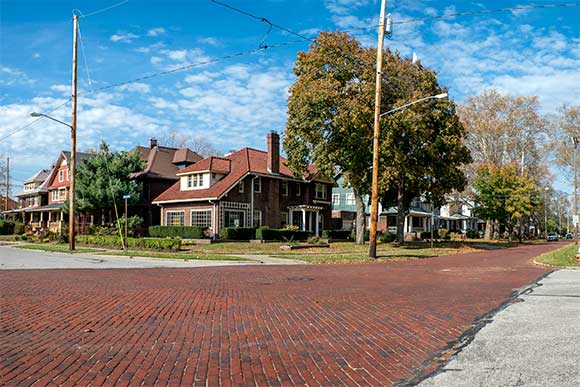

What you may not know is that East Boulevard, the road that runs along the upper level of the park, parallel to MLK, is perhaps even more beautiful.

It offers not only additional gardens, but one of the grandest residential districts in the city, chock full of stone-detailed apartment houses and immaculately landscaped mansions.

“So many people are shocked when they come up here,” says India Pierce Lee, who’s lived on a street just off East Boulevard with her husband since 1995. “They may have lived in Cleveland all their lives, but they had no idea this existed.”

A hidden neighborhood

A hidden neighborhood

“This” is the East Boulevard Historic District, a narrow band of the Glenville neighborhood roughly between Superior Avenue and St. Clair Avenues.

Lee, a program director focusing on neighborhoods, housing and community development for The Cleveland Foundation, remembers the stunned faces of attendees of the first annual One World Festival in September. “We had people calling realtors,” she says. “They couldn’t believe how beautiful the neighborhood is.”

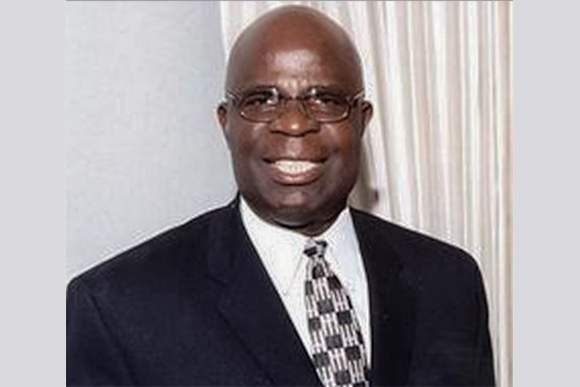

On an overcast afternoon, Lee strolls through the district with her friend and neighbor John Anoliefo, executive director of the Famicos Foundation. Famicos is a community development corporation with a special focus on Glenville.

The two point out stately brick houses where rows of groomed hedges guard leaded bay windows. Each one sports a different array of fine details: Spanish-tile roofs, copper gutters, pointed gables.

“These were signature homes, built by steel magnates, doctors, lawyers,” says Anoliefo. “You really have to fall in love with this kind of house to be willing to take care of it.”

Lee nods. At her own house, a tall gray-and-white Colonial with a steeply pitched roof, she says she and her husband plan for about one big project a year, though the work often expands way beyond what they’d anticipated.

“These houses are no joke,” she says with a laugh somewhere between proud and rueful.

It’s a mix of sentiment familiar to anyone who’s owned an old house. But the houses in the East Boulevard Historic District -- a local landmark district that stretches along East Boulevard and its side streets -- are unique for a couple of reasons.

First, they were built at a scale and level of opulence rarely seen in the city of Cleveland, dominated as it is by modest wood frame houses targeted at workers who flocked here during the Industrial Revolution.

Second, they’re located in one of the city’s most foreclosure-scarred neighborhoods. In 2007 alone, Glenville suffered 525 foreclosure filings -- more than any other part of the city, including Slavic Village, which received more national media attention. The foreclosures have led to an all-too-familiar cycle of vacancy and, in many cases, demolition.

Then there’s the much older trauma of the Glenville shoot-out of 1969. The event started on a hot summer day as a conflict between black activist Fred Evans and a police officer who threatened to tow his car. It devolved into four days of rioting and looting that left seven people dead and much of the neighborhood in ruins. Then-mayor Carl Stokes called in the Ohio National Guard to restore order.

For many Clevelanders, the shoot-out epitomized the decline and chaos of the city overall. Cleveland’s population was already on the wane then, due to suburbanization, job loss and racial tension, and it fell off even faster during the 1970s.

Glenville, which was 70 percent white and Jewish in 1930, was 90 percent African American by 1960. At the same time, money and resources were draining out to the suburbs.

Today, if you step outside the boundaries of the historic district, the tumult of the past 50 years immediately becomes visible: weedy lots, boarded up houses, a stray dog roaming free.

Most of Glenville’s houses aren’t as grand as those along East Boulevard, but they’re solidly built Colonials of the type that fetch $150,000 or more in the nearby suburb of Cleveland Heights. Here, sales prices are often a tenth that.

History and community

What’s kept East Boulevard so stable while the rest of the neighborhood continues to struggle?

First, Anoliefo says, there’s the housing stock itself -- unique and beautiful enough to attract people with a love of historic architecture. Local luminaries who’ve lived here over the years include television newscaster Leon Bibb and former mayor Michael White.

German Cultural Garden off of East Blvd

German Cultural Garden off of East Blvd

Rockefeller Park, too, is becoming an asset after years of being synonymous with crime and disarray. During the park’s nadir in the 1970s, many cultural groups removed sculptures from the cultural gardens to protect them from being stolen or vandalized. But some of the sculptures have now returned, and recent immigrant groups are sponsoring new gardens.

Most important, Lee says, is the involvement and commitment of its residents. When a house comes on the market, she and her neighbors spring into action.

“We do a lot of recruiting,” she says. She turns to Anoliefo, teasing. “When John got the job at Famicos, we basically forced him to move in.”

Anoliefo smiles. “I wouldn’t have it any other way,” he says. “Not just for the house, but because I feel and see everything that everybody in the neighborhood else sees and feels.

“If I didn’t, people could tell me to sit down in meetings. They’d say I don’t understand because I don’t live here -- and they’d be right.”

A rising profile and new challenges

There are some signs that East Boulevard’s relative anonymity -- at least among whites and newcomers -- may be coming to an end. New populations are finding not only it but the southernmost part of Glenville, bordering University Circle.

As the real estate market has recovered, Anoliefo has seen recent sales prices in and around East Boulevard for $280,000 or more. Two houses in the neighborhood have competing offers.

Heritage Lane

Heritage Lane

Heritage Lane, a project that converted 13 historic doubles on East 105th Street into large single-family homes with contemporary amenities, saw no sales at all 2008 and 2009. Now, just three houses remain unsold, and one of those is under contract.

“The buyers run the gamut,” Anoliefo says. “We have people who’ve come from the inner ring suburbs, from Lake County, from outside of Ohio. They’re black, white, Asian.”

Encouraging the in-migration is an income-blind mortgage assistance program sponsored by the Cleveland Foundation and some of University Circle’s largest institutions. The program offers up to $30,000 in down payment assistance to full-time employees of select institutions.

Others are finding Glenville on their own.

Doc Harrill, a hiphop artist and activist, lives on East 115th Street near Wade Park Avenue. His house is within easy walking distance of the Cleveland Museum of Art and other University Circle institutions. He and his wife moved into their house in 2006 partly because it was affordable and large enough to provide space for a family -- they now have two kids -- and a home recording studio.

Doc & Anne Harrill at their home near Wade Park Avenue

Doc & Anne Harrill at their home near Wade Park Avenue

He also loved the idea of living in a racially and economically diverse neighborhood. The Harrills were the only white family on their block at the time. Now, a handful of other white and Asian newcomers have moved in.

“It’s not a bad thing,” he says. “But I’m interested in how we can build trust and rapport between people who’ve lived here forever, and people who are newer. How do we live together?”

In part to encourage relationships across race lines, Harrill founded Fresh Camp, a camp that teaches both recording and urban agriculture skills to youth from Glenville and University Circle.

Anoliefo, too, is keeping an eye on the neighborhood’s slowly changing demographics.

“Each time you bring new people to a neighborhood where there are existing residents, there’s going to be tension,” he says.

Most of the tension in Glenville has been over economic privilege and resources rather than race, he says.

“People question why new people who are coming into the neighborhood are getting tax abatement and mortgage assistance. How about those who’ve been there for years?”

In response, Famicos offers home repair assistance to longtime homeowners. It also offers a slate of social service programs for youth and adults.

Lee and Anoliefo say what they and their neighbors most want in the future is a strong neighborhood of involved and active residents.

“The generations that were here for all that tension in the past -- they’re raising their children not to witness something like that,” Anoliefo says. “We’re all looking forward to what Glenville will be, not what it was.”

Photos Bob Perkoski