east meets west: a new generation of businesses bridging the old divide

Whether you’ve lived in Cleveland your whole life or whether you’re a blow-in from other cities, you’d have to live in a cave not to have heard the jokes about needing a passport to traverse the Cuyahoga River.

In his 2000 book, First and Last Seasons, Cleveland writer Dan McGraw writes, “From the moment you emerge from the womb in Cleveland, you are defined by what side of the Cuyahoga River you were born on.”

Yet if you ask a millennial about this divide, their eyebrows usually rise and knit over their thick black frame glasses in confusion. Some will have a dim recollection of a grandmother whispering, “You’re not really going downtown/to the east side/to the west side, are you?”

Why this rancor? Why this east/west schism?

In The Story of Ohio City (1968), Richard N. Campen tells us how it all goes back to “The Bridge War of 1836” when Cleveland and the then-independent city of Ohio City (aka City of Ohio) shared ownership of the only bridge across the river, a floating bridge, that connected the two towns. Cleveland then erected a permanent bridge, the Columbus Road Bridge, which spanned from Pearl Road to Cleveland's city center and completely bypassed Ohio City. In retaliation, Ohio City, whose battle cry became "Two bridges or none," boycotted the new bridge, which in turn prompted Cleveland City Council to remove their half of the floating bridge.

Campen writes, "On 31 Oct. 1836 a mob of Ohio City residents armed with guns, crowbars, axes, and other weapons set off to finish the destruction, only to be met by Cleveland mayor John W. Wiley and a group of armed Cleveland militiamen. Three men were seriously wounded in the ensuing riot before the county sheriff arrived to end the violence and make several arrests. A court injunction prevented any further interference with the bridge, and the courts resolved the issue by ruling that there should be more than one bridge crossing."

The whole ordeal was even memorialized shortly afterwards in a mock-epic poem entitled, “Battle of the Bridge” by D.W. Cross, Esq., a lawyer and prominent coal operator. Its closing stanza celebrates the end of the war:

“The sow was paid for and the war was o’er.

A sober second thought their actions guide,

And broils no more the “West” and “East” divide,

A bridge high-level spans the gulf between,

Crowning, harmonious, both in bays of green.”

Flash forward nearly 200 years, and Cross would surely be glad to see folks crossing the river via multiple bridges to visit each “bay of green.” He would be especially proud that for a new generation, crossing the old divide at one’s peril is quickly becoming a faded, almost nostalgic memory in our collective consciousness.

These days, west side shops are popping up on the east side, while east side cultural institutions are making inroads west. But Cleveland’s indie merchants and cultural stewards aren’t just creating cookie cutter versions of themselves. Instead, they’re tailoring their products and services, creating a new cross-cultural exchange that promises (dare we say it) to bridge the historic east-west divide.

How the east and west were one

Several people point to a pivotal moment they view as a kind of great thaw in east-west relations, when in May of 2013 the Cleveland Orchestra presented a week-long neighborhood residency in the Gordon Square Arts District.

Joan Katz, Director of Education & Community Programs for the Cleveland Orchestra, says the “distance between the east and west sides of Cleveland got a lot shorter as the result of the Orchestra spending so much time in the west side neighborhoods of Gordon Square and Lakewood [in May 2014].”

Charlie Lawrence, President and CEO of The Music Settlement (TMS), agrees, adding that “people on the west side felt honored that the Orchestra sought a connection and spent time in their neighborhood.”

TMS is continuing this new tradition of east/west collaboration. When the former owners of The Bop Stop donated the shuttered jazz club to The Music Settlement (TMS) in December 2013, Lawrence and his team began making plans for a second campus that would offer music classes, music therapy and early childhood education. They wanted the venue to meet the needs of the west side.

Lawrence sees the expansion as a perfect fit and recalls a time when TMS had locations in several parts of town. “TMS is now able to more fully return to its mission as a settlement that serves everyone in the community, including the large Hispanic population and growing African immigrant newcomers" on the west side,” he says.

Programming will reflect the west side community with more Latin music programming, he adds. Just this weekend, The Bop Stop at the Music Settlement offered a concert with a jazz/flute duo performing latin and rock tunes.

Nearby is the Transformer Station, which emerged two years ago from a partnership between Fred and Laura Bidwell and the Cleveland Museum of Art. The popular summer concert series, Ohio City Stages, was added in 2013.

Hands across the Cuyahoga

Yet it isn’t just large east side cultural institutions crossing the bridge, nor is it a case of one neighborhood cannibalizing another’s appeal or making it more convenient for everyone to stay on their side of town.

“Institutions have to reach out across the city,” opines Chris Ronayne, President of University Circle Incorporated (UCI), on the need for east-west exchange. “We can’t only rely on folks from the Heights to come down the hill to the orchestra. [That’s why] we’re promoting cross-town collaboration and exploration.”

Small, local and predominantly west side business owners are, too. Kim Jenkins, proprietor of Rising Star Coffee Roasters, says that “just as east side institutions are coming west to Ohio City, west side businesses are coming east."

Customers have followed apace. Jenkins says that people west of the river visit Rising Star’s new Little Italy coffee shop, while east siders also visit the Hingetown shop. He tells the story of a doctor who lives in Cleveland Heights and rides her bike to work on the near west side. She used to stop at the Hingetown shop on her way, but now she gets her caffeine shot before crossing the bridge.

Programming at the new Rising Star location now includes the west side tradition of Thursday Night Latte Art Throwdowns, where baristas put their skills to the test and compete for cash as spectators BYO beer and snacks and cheer them on.

Rising Star partner and quality control director John Johnson doesn’t see an east/west divide, but rather sees public transportation as preventing more crossover. As a resident of the St. Clair Superior neighborhood, he laments the multiple bus trips he needs to take to get from one part of town to another.

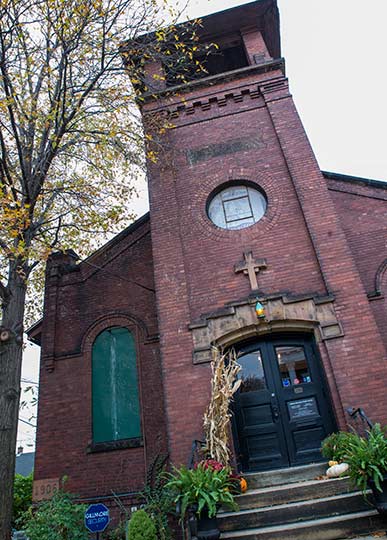

Urban Orchid is another west side businesses that recently opened an east side location – in a heavenly, light-filled former church on Murray Hill Road. Co-owner Jeff Zelmer says Little Italy gets more foot traffic than Hingetown, and they’ve been able to better serve their east side customer base from the new location.

Down the red brick street, Travis Peebles, co-owner of Blazing Saddle Cycles, has also seen booming business at his Little Italy shop. “Do you know what the biggest bicycle intersection in Cleveland is?” he poses. "Lake/Detroit/74th, right where we are [at the Detroit Shoreway location]. And the second biggest one is right across the street at Edgehill and Murray Hill [the new location]."

The presence of multiple locations hasn't stifled cross-town traffic, say Peebles and others -- instead, it has promoted a new kind of east-west exchange.

Says Gabe Pollack, manager of the Bop Stop at the Music Settlement, on traveling between east and west: "At some point people have to realize it takes 12 minutes to drive from The Music Settlement to the Bop Stop. That's nothing in any other city."

Happy on both sides of town

The Happy Dog, a business that one might say bookends two popular cultural districts in the city, is mixing up its programming to appeal to its customers. Owner Sean Watterson is originally from the east side but now lives on the west side. When UCI courted him to lease the old Euclid Tavern, he did not want to wholly replicate the classic West 58th Street beer and hotdog joint.

“Tradition was important,” he says of the famed Euclid Tavern venue, now named the Happy Dog at the Euclid Tavern to honor its 104-year history as a bar. “We wanted people to walk in and recognize this place that has so much history."

Indeed, "the Euc," as it's known to so many Clevelanders, is the city's second oldest bar site and has hosted everyone from Mr. Stress to Chrissie Hynde. Watterson says the hot dog toppings are different at the Euclid Tavern location and patrons are coming over to check them out. He’s just at the beginning of creating the programming. In 2010, he invited members of The Cleveland Orchestra to perform at the Happy Dog, and that opened the door to all kinds of collaborations, including talks by scientists, writers, and academics on topics ranging from the origin of the universe to global affairs.

Tom McNair, Executive Director of Ohio City Incorporated, is thrilled to see many of his neighborhood’s entrepreneurs expanding eastward. He believes that connectivity is essential to helping businesses succeed and helping customers navigate between both sides of town.

For example, OCI has been pushing for protected bike lanes on Lorain Avenue at the same time that Bike Cleveland has been exploring the “Midway” concept – protected bike lanes that could run in the middle of a street – in St Clair/Superior. Now they’re collaborating on a potential bikeway that would connect the city.

“Ultimately, the city of Cleveland is more successful if we’re all connected,” says McNair.

A lot of Clevelanders on both sides of the river tend to think of the near west side (Ohio City, Tremont, Gordon Square and other neighborhoods) as an extension of downtown Cleveland. They also refer to University Circle as being on the eastside. However, it seems of late that Cleveland is transforming from a city that has an east/west mentality into a city with an uptown and a downtown.

That’s right, it might finally be time to lay down our pitchforks once and for all! No more bridge wars, brave Clevelanders. And yet a chasm still remains. As Euclid Avenue slowly returns to life, it is the long, dreary hauls up and down Cedar, Carnegie, Chester, Superior and St. Clair, the routes that link uptown with downtown, that could very likely be the next battle for Cleveland ...