Old Brooklyn celebrates the opening of its first brand-new school building in 54 years

Yesterday, a festive ribbon-cutting celebration feted the opening of William Rainey Harper elementary school—replete with a drum corps, performances by the school’s Pre-K students, and an appearance by Cleveland Metropolitan School District CEO Eric Gordon.

The school opened its doors to the inaugural groups of Pre-K to third grade students on August 13, becoming only the third CMSD school to follow the International Baccalaureate model. (The other two schools are the Campus International elementary and high schools downtown.) It’s also the first new public school to be constructed from the ground up in Old Brooklyn since the mid-1960s.

The school opened its doors to the inaugural groups of Pre-K to third grade students on August 13, becoming only the third CMSD school to follow the International Baccalaureate model. (The other two schools are the Campus International elementary and high schools downtown.) It’s also the first new public school to be constructed from the ground up in Old Brooklyn since the mid-1960s.

An inquiry-based learning model, William Rainey Harper’s curriculum is designed to promote natural curiosity, build research skills, and foster independence in learning. Students begin learning Spanish in preschool, and physical education classes focus on holistic wellness by integrating fitness activities with lessons on healthy eating.

“International Baccalaureate teaches students how to not only care about themselves, but others around them, their local community, and the world,” says principal Ajayi Monell. “We encourage being a risk-taker and [embracing] lifelong learning with no fear. Kids are often so afraid of making mistakes in school that their creativity is stifled because they don’t want to be wrong. But in life, sometimes we learn our best lessons from mistakes.”

Like Campus International—which has a waitlist and lottery system due to its popularity—William Rainey Harper is already attracting interest from all over the city, with students traveling from as far as Westlake to enroll. Monell says the Pre-K program is already at capacity, but openings do remain in the K-3 classrooms. (Though the school currently serves Pre-K through third grade, one grade will be added each year until it serves grades K-8.)

Like Campus International—which has a waitlist and lottery system due to its popularity—William Rainey Harper is already attracting interest from all over the city, with students traveling from as far as Westlake to enroll. Monell says the Pre-K program is already at capacity, but openings do remain in the K-3 classrooms. (Though the school currently serves Pre-K through third grade, one grade will be added each year until it serves grades K-8.)

“When you look at schools nationally, many of our forward-thinking, growing communities are ensuring that an International Baccalaureate model is part of their portfolio of schools,” says Christine Fowler-Mack, pointing to Shaker Heights as a local example. “It’s a proven model not only for core competency, but also an approach to additional skills and perspective that fits in with what kids will need for their future.”

The opening of the school also ticks off a box toward an overall goal for CMSD schools in Old Brooklyn. “Old Brooklyn has had really steady and improving academic performance, so our goal has been to take schools from good to great,” says Fowler-Mack. “One of the ways we’ve accomplished that is by increasing the number of seats available to students in Old Brooklyn.”

Melding inclusion and innovation

William Rainey Harper joins a portfolio of 13 schools in Old Brooklyn, many of which also follow innovative models. Case in point: Facing History New Tech (FHNT). The small CMSD high school occupies the third floor of Charles A. Mooney Elementary, boasting a 92.7 percent graduation rate (compared to a district total of 72.1 percent).

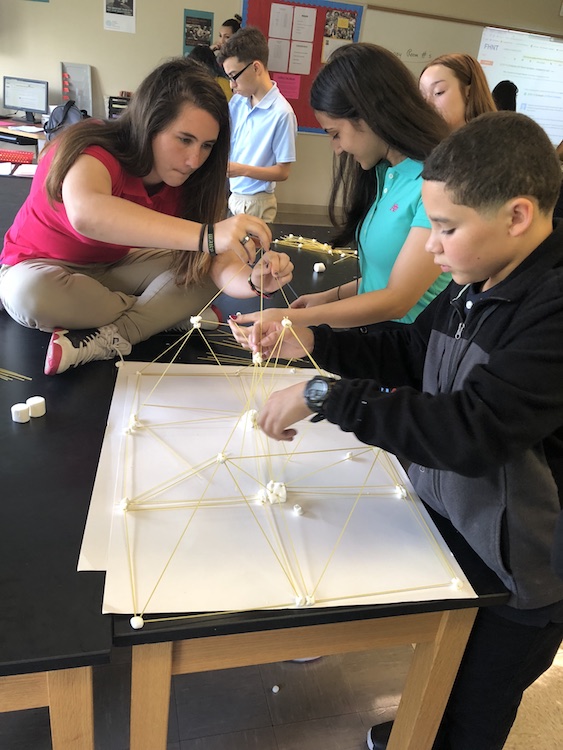

Open since 2012, FHNT is the first school of its kind in the nation to combine the Facing History and Ourselves curriculum with the New Tech Network’s project-based learning model. All-inclusiveness is more than a mission statement, but rather a community philosophy deeply ingrained in the fabric of the diverse student body. (The school's enrollment is about 50 percent white, 25 percent hispanic, 20 percent African-American, and 5 percent other with at least 19 countries represented.)

Open since 2012, FHNT is the first school of its kind in the nation to combine the Facing History and Ourselves curriculum with the New Tech Network’s project-based learning model. All-inclusiveness is more than a mission statement, but rather a community philosophy deeply ingrained in the fabric of the diverse student body. (The school's enrollment is about 50 percent white, 25 percent hispanic, 20 percent African-American, and 5 percent other with at least 19 countries represented.)

Kids with special needs are integrated into general classrooms, with extra assistance from special education teachers when necessary. LGBTQ students are welcomed in a supportive environment.

“Word has spread in the community that we’re a safe space for LGBTQ students,” explains principal Marc Engoglia, who was named a Mentor of the Year in 2014 by MLB.com. “For example, although I cannot change a child’s name in the system, a transgender student would be referred to by their preferred name and pronouns, and given a student email address appropriate to the gender they identify with.”

Since group projects are an integral part of study, team-building is a natural byproduct of everyday activities—organically creating a barrier for clique-building and bullying. Pupils work inside classrooms configured roundtable-style rather than at individual desks. Discipline is handled with conversation before any consequences typically implemented for disruptions at school (like suspension or expulsion), which tends to result in more prompt and thorough conflict resolution.

Since group projects are an integral part of study, team-building is a natural byproduct of everyday activities—organically creating a barrier for clique-building and bullying. Pupils work inside classrooms configured roundtable-style rather than at individual desks. Discipline is handled with conversation before any consequences typically implemented for disruptions at school (like suspension or expulsion), which tends to result in more prompt and thorough conflict resolution.

A staff-supervised “care room” provides a comforting respite in an old planetarium adorned with students’ painted artwork for self-imposed time-outs, and gives Engoglia another opportunity to engage with a student or intervene with a counselor or school psychologist if frequent visits raise a red flag that more persistent problems may exist.

“FHNT is really doing a tremendous job—this school is the real deal,” says Cleveland City Council president Kevin Kelley, a resident of Old Brooklyn. “They’ve taken kids that come from challenged homes and have produced strong students and great graduates."

FHNT is influencing other schools in Old Brooklyn as well, as nearby charter school Constellation Old Brooklyn has implemented a social justice class based on FHNT curriculum.

Reinventing Rhodes

In an IFF report released in 2014, Old Brooklyn was named as one of Cleveland’s “highest-need neighborhoods” for improving educational options. The report's citywide recommendations included replicating high-performing schools, improving mid-performing schools, and targeting the lowest-performing schools for turnaround or closure.

While William Rainey Harper is a great example of the “replication” goal, recent changes at James F. Rhodes High School speak to the “improvement” side of the equation. In December 2016, the 84-year-old traditional high school announced that it would become home to two smaller niche schools: the Rhodes School of Environmental Studies (year-round) and Rhodes College and Career Academy (a choice informed by design teams comprised of school educators and community members).

While William Rainey Harper is a great example of the “replication” goal, recent changes at James F. Rhodes High School speak to the “improvement” side of the equation. In December 2016, the 84-year-old traditional high school announced that it would become home to two smaller niche schools: the Rhodes School of Environmental Studies (year-round) and Rhodes College and Career Academy (a choice informed by design teams comprised of school educators and community members).

Opened in 2017, the former focuses on life sciences, social sciences, and business with a project-based approach, while the latter takes a mastery-based approach with personalized career plans, real-world professional experiences, and technology-focused learning.

“With this approach, students get the best of both worlds,” says Fowler-Mack. “Families get a choice in how each student will learn best, while the school can still continue the tradition of Rhodes by partnering with alumni and coming together for athletics or music programs.”

“With this approach, students get the best of both worlds,” says Fowler-Mack. “Families get a choice in how each student will learn best, while the school can still continue the tradition of Rhodes by partnering with alumni and coming together for athletics or music programs.”

The Rhodes School of Environmental Studies also extends its ties to Old Brooklyn with a partnership with the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, bolstered by a $300,000 grant from KeyBank Foundation. Students are able to use the 183-acre park as a classroom of sorts, working with the animals and taking courses on wildlife conservation.

Investing in the future

Councilman Kelley points to William Cullen Bryant elementary school as having made great strides in recent years—largely due to recent improvements such as the addition of air-conditioned, wired modular units for the sixth, seventh, and eighth grades “to take pressure off the crowded classrooms,” according to Kelley.

Kelley also devoted $320,000 of discretionary council funds to purchasing iPad devices, which will take WCB one step closer to designation as an Apple Distinguished School. “We want to educate our kids in a 21st century environment,” says Kelley.

Kelley also devoted $320,000 of discretionary council funds to purchasing iPad devices, which will take WCB one step closer to designation as an Apple Distinguished School. “We want to educate our kids in a 21st century environment,” says Kelley.

The Old Brooklyn Community Development Corporation has also invested energy in furthering Old Brooklyn’s education offerings, as the only CDC in Cleveland that has a staff member dedicated solely to education. Since 2016, the OBCDC has also hosted a committee comprised of principals of nine Old Brooklyn schools, putting a focus on education as an integral part of its master planning.

“The partnership that we have in this area between principals of our schools is incredibly unique,” affirms Cherie Kaiser, principal of Constellation Old Brooklyn. “Whether parochial, private or charter, we are all coming together and participating in meetings with OBCDC and their education committee, talking about the community-at-large and education’s role is in the community. We're all working together for the good of all of the children in Old Brooklyn, instead of having our own particular agendas.”

Kelley agrees that the CDC’s focus on education has been a boon for the community—making good on the neighborhood's "brand" as an "accessible, family-friendly neighborhood where business and people come to grow."

“When you’re looking at how to stabilize a community, education is core,” says Kelley. “The addition of an education coordinator is an acknowledgement that education is community development.”

Looking at the big picture, Kelley believes the collective efforts of the schools, community, and OBCDC are helping to reshape the narrative of urban education.

“Between CMSD, charter, and parochial schools, there isn’t a better option than Old Brooklyn for getting your child a great K-8 education,” says Kelley, whose daughter will be entering third grade at William Rainey Harper this year. “The options available here are at least as good as any suburban district.”

This article is part of our On the Ground - Old Brooklyn community reporting project in partnership with Old Brooklyn Community Development Corporation, Greater Cleveland Partnership, Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, Cleveland Development Advisors, and Cleveland Metropolitan School District. Read the rest of our coverage here.

About the Author: Jen Jones Donatelli

As an enthusiastic CLE-vangelist, Jen Jones Donatelli enjoys diving headfirst into her work with FreshWater Cleveland. Upon moving back to Cleveland after 16 years in Los Angeles, Jen served as FreshWater's managing editor for two years (2017-2019) and continues her work with the publication as a contributing editor and host of the FreshFaces podcast.

When not typing the day away at her laptop, she teaches writing and creativity classes through her small business Creative Groove, as well as Literary Cleveland, Cleveland State University, and more. Jen is a proud graduate of Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism.